Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

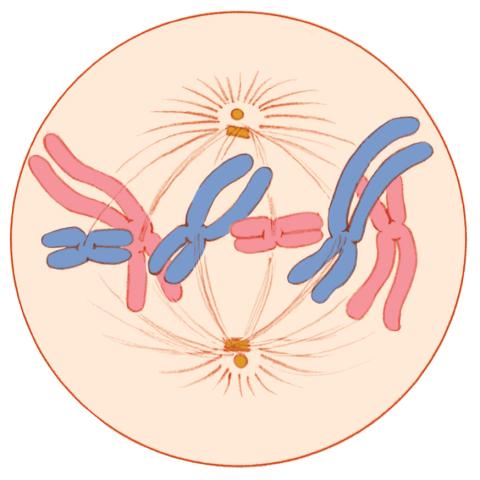

1329: Mitosis - metaphase

1329: Mitosis - metaphase

A cell in metaphase during mitosis: The copied chromosomes align in the middle of the spindle. Mitosis is responsible for growth and development, as well as for replacing injured or worn out cells throughout the body. For simplicity, mitosis is illustrated here with only six chromosomes.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

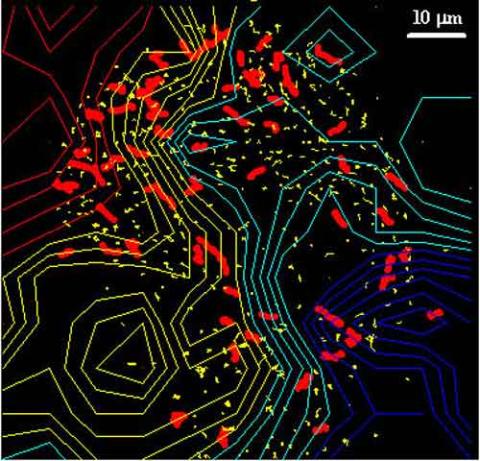

2310: Cellular traffic

2310: Cellular traffic

Like tractor-trailers on a highway, small sacs called vesicles transport substances within cells. This image tracks the motion of vesicles in a living cell. The short red and yellow marks offer information on vesicle movement. The lines spanning the image show overall traffic trends. Typically, the sacs flow from the lower right (blue) to the upper left (red) corner of the picture. Such maps help researchers follow different kinds of cellular processes as they unfold.

Alexey Sharonov and Robin Hochstrasser, University of Pennsylvania

View Media

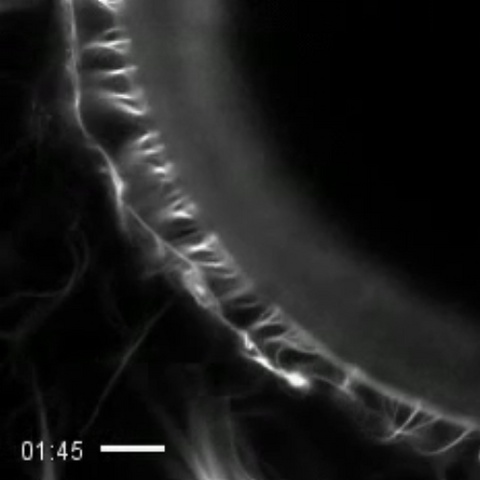

3494: How cilia do the wave

3494: How cilia do the wave

Thin, hair-like biological structures called cilia are tiny but mighty. Each one, made up of more than 600 different proteins, works together with hundreds of others in a tightly-packed layer to move like a crowd at a ball game doing "the wave." Their synchronized motion helps sweep mucus from the lungs and usher eggs from the ovaries into the uterus. By controlling how fluid flows around an embryo, cilia also help ensure that organs like the heart develop on the correct side of your body.

Zvonimir Dogic, Brandeis University

View Media

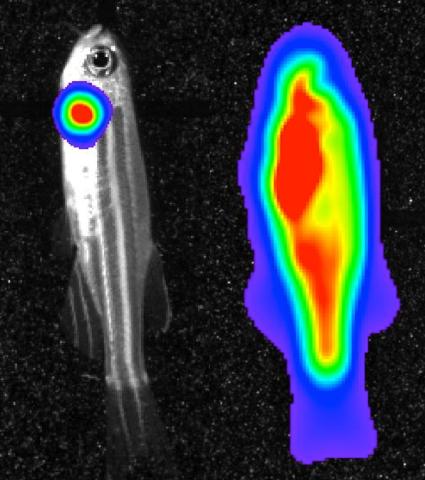

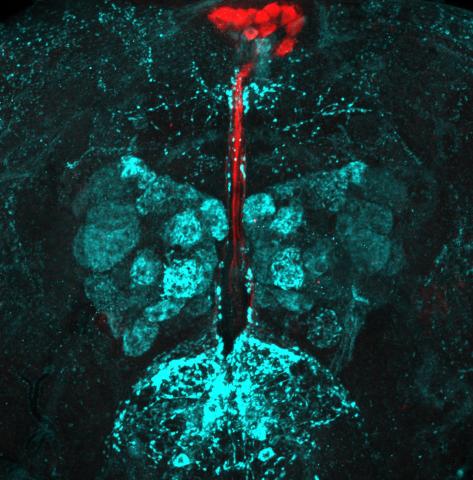

3559: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish 04

3559: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish 04

Luciferase-based imaging enables visualization and quantification of internal organs and transplanted cells in live adult zebrafish. This image shows how luciferase-based imaging could be used to visualize the heart for regeneration studies (left), or label all tissues for stem cell transplantation (right).

For imagery of both the lateral and overhead view go to 3556.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For imagery of the lateral view go to 3558.

View Media

For imagery of both the lateral and overhead view go to 3556.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For imagery of the lateral view go to 3558.

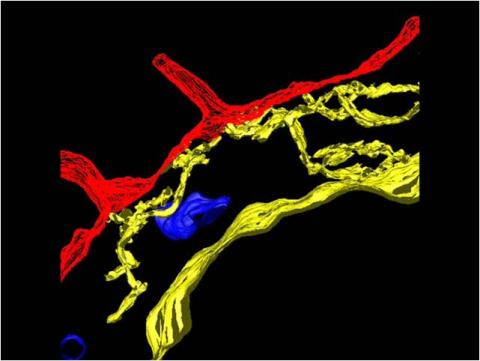

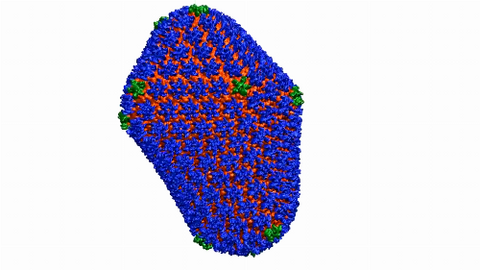

2636: Computer model of cell membrane

2636: Computer model of cell membrane

A computer model of the cell membrane, where the plasma membrane is red, endoplasmic reticulum is yellow, and mitochondria are blue. This image relates to a July 27, 2009 article in Computing Life.

Bridget Wilson, University of New Mexico

View Media

1294: Stem cell differentiation

1294: Stem cell differentiation

Undifferentiated embryonic stem cells cease to exist a few days after conception. In this image, ES cells are shown to differentiate into sperm, muscle fiber, hair cells, nerve cells, and cone cells.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

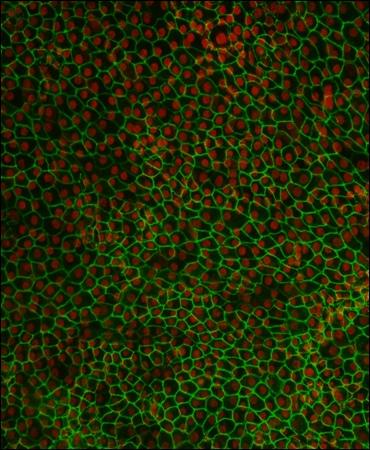

3287: Retinal pigment epithelium derived from human ES cells 02

3287: Retinal pigment epithelium derived from human ES cells 02

This image shows a layer of retinal pigment epithelium cells derived from human embryonic stem cells, highlighting the nuclei (red) and cell surfaces (green). This kind of retinal cell is responsible for macular degeneration, the most common cause of blindness. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Related to image 3286

David Buckholz and Sherry Hikita, University of California, Santa Barbara, via CIRM

View Media

1056: Skin cross-section

1056: Skin cross-section

Cross-section of skin anatomy shows layers and different tissue types.

National Institutes of Health Medical Arts

View Media

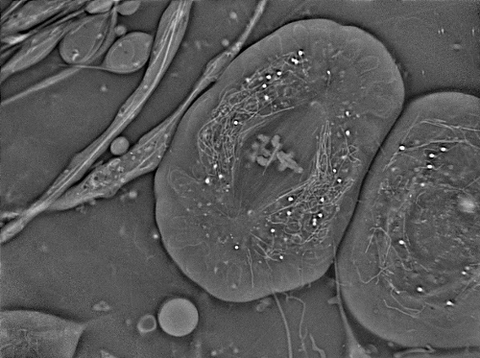

1058: Lily mitosis 01

1058: Lily mitosis 01

A light microscope image shows the chromosomes, stained dark blue, in a dividing cell of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

6389: Red and white blood cells in the lung

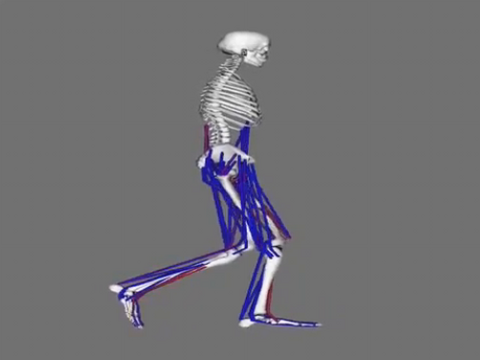

6598: Simulation of leg muscles moving

6598: Simulation of leg muscles moving

When we walk, muscles and nerves interact in intricate ways. This simulation, which is based on data from a six-foot-tall man, shows these interactions.

Chand John and Eran Guendelman, Stanford University

View Media

3618: Hair cells: the sound-sensing cells in the ear

3618: Hair cells: the sound-sensing cells in the ear

These cells get their name from the hairlike structures that extend from them into the fluid-filled tube of the inner ear. When sound reaches the ear, the hairs bend and the cells convert this movement into signals that are relayed to the brain. When we pump up the music in our cars or join tens of thousands of cheering fans at a football stadium, the noise can make the hairs bend so far that they actually break, resulting in long-term hearing loss.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Henning Horn, Brian Burke, and Colin Stewart, Institute of Medical Biology, Agency for Science, Technology, and Research, Singapore

View Media

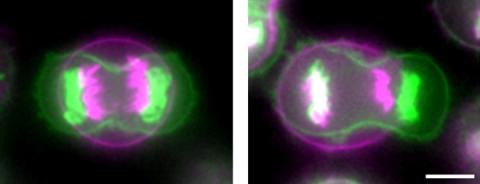

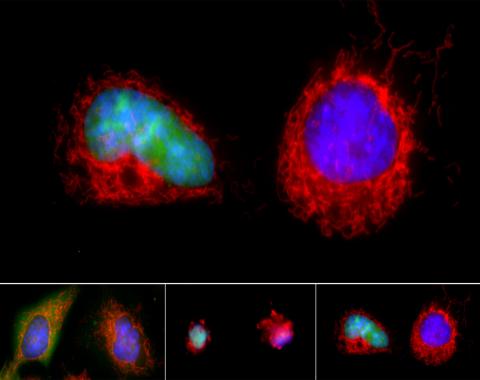

3648: Symmetrically and asymmetrically elongating cells

3648: Symmetrically and asymmetrically elongating cells

Merged fluorescent images of symmetrically (left) or asymmetrically (right) elongating HeLa cells at the end of early anaphase (magenta) and late anaphase (green). Chromosomes and cortical actin are visualized by expressing mCherry-histone H2B and Lifeact-mCherry. Scale bar, 10µm. See the PubMed abstract of this research.

Tomomi Kiyomitsu and Iain M. Cheeseman, Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research

View Media

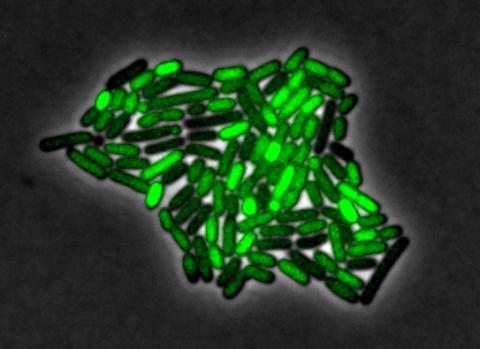

3253: Pulsating response to stress in bacteria

3253: Pulsating response to stress in bacteria

By attaching fluorescent proteins to the genetic circuit responsible for B. subtilis's stress response, researchers can observe the cells' pulses as green flashes. In response to a stressful environment like one lacking food, B. subtilis activates a large set of genes that help it respond to the hardship. Instead of leaving those genes on as previously thought, researchers discovered that the bacteria flip the genes on and off, increasing the frequency of these pulses with increasing stress. See entry 3254 for the related video.

Michael Elowitz, Caltech University

View Media

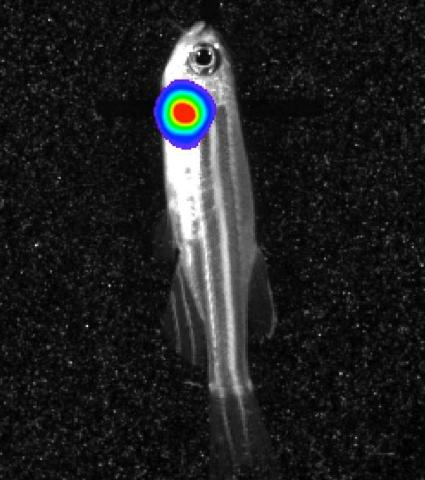

3558: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish - lateral view

3558: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish - lateral view

Luciferase-based imaging enables visualization and quantification of internal organs and transplanted cells in live adult zebrafish. In this image, a cardiac muscle-restricted promoter drives firefly luciferase expression (lateral view).

For imagery of both the lateral and overhead view go to 3556.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For more information about the illumated area go to 3559.

For imagery of both the lateral and overhead view go to 3556.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For more information about the illumated area go to 3559.

Kenneth Poss, Duke University

View Media

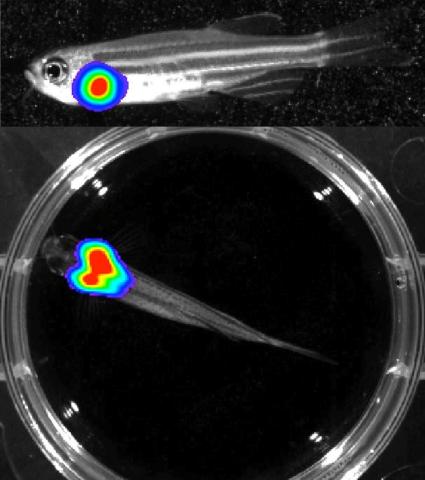

3556: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish - lateral and overhead view

3556: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish - lateral and overhead view

Luciferase-based imaging enables visualization and quantification of internal organs and transplanted cells in live adult zebrafish. In this image, a cardiac muscle-restricted promoter drives firefly luciferase expression. This is the lateral and overhead (Bottom) view.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For imagery of the lateral view go to 3558.

For more information about the illumated area go to 3559.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For imagery of the lateral view go to 3558.

For more information about the illumated area go to 3559.

Kenneth Poss, Duke University

View Media

6898: Crane fly spermatocyte undergoing meiosis

6898: Crane fly spermatocyte undergoing meiosis

A crane fly spermatocyte during metaphase of meiosis-I, a step in the production of sperm. A meiotic spindle pulls apart three pairs of autosomal chromosomes, along with a sex chromosome on the right. Tubular mitochondria surround the spindle and chromosomes. This video was captured with quantitative orientation-independent differential interference contrast and is a time lapse showing a 1-second image taken every 30 seconds over the course of 30 minutes.

More information about the research that produced this video can be found in the J. Biomed Opt. paper “Orientation-Independent Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) Microscopy and Its Combination with Orientation-Independent Polarization System” by Shribak et. al.

More information about the research that produced this video can be found in the J. Biomed Opt. paper “Orientation-Independent Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) Microscopy and Its Combination with Orientation-Independent Polarization System” by Shribak et. al.

Michael Shribak, Marine Biological Laboratory/University of Chicago.

View Media

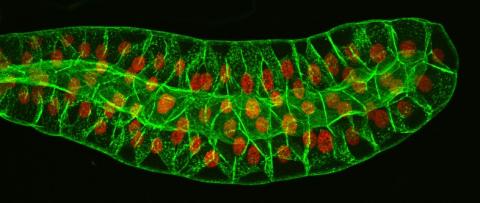

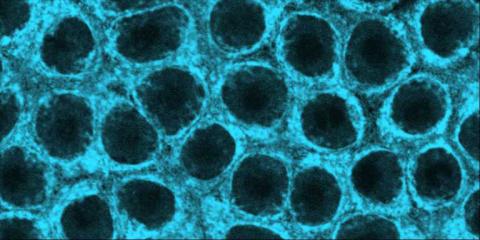

3656: Fruit fly ovary_2

3656: Fruit fly ovary_2

A fruit fly ovary, shown here, contains as many as 20 eggs. Fruit flies are not merely tiny insects that buzz around overripe fruit--they are a venerable scientific tool. Research on the flies has shed light on many aspects of human biology, including biological rhythms, learning, memory and neurodegenerative diseases. Another reason fruit flies are so useful in a lab (and so successful in fruit bowls) is that they reproduce rapidly. About three generations can be studied in a single month. Related to image 3607.

Denise Montell, University of California, Santa Barbara

View Media

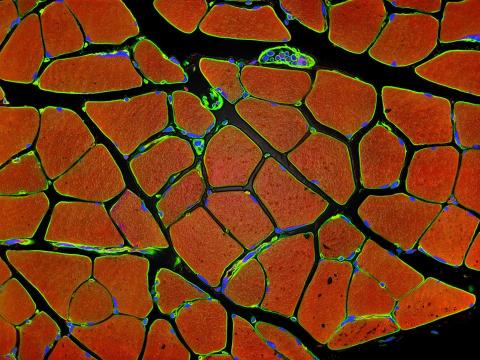

3677: Human skeletal muscle

3677: Human skeletal muscle

Cross section of human skeletal muscle. Image taken with a confocal fluorescent light microscope.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

2438: Hydra 02

2438: Hydra 02

Hydra magnipapillata is an invertebrate animal used as a model organism to study developmental questions, for example the formation of the body axis.

Hiroshi Shimizu, National Institute of Genetics in Mishima, Japan

View Media

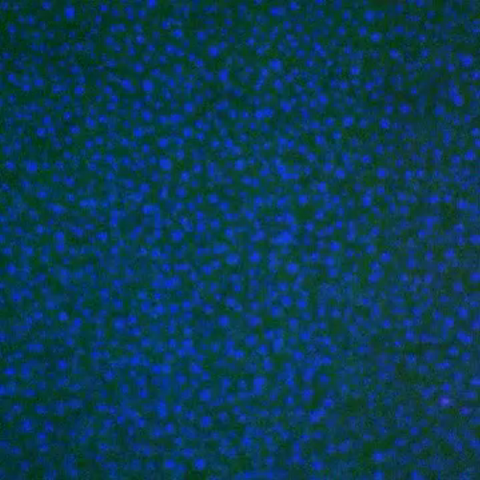

3449: Calcium uptake during ATP production in mitochondria

3449: Calcium uptake during ATP production in mitochondria

Living primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Mitochondria (green) stained with the mitochondrial membrane potential indicator, rhodamine 123. Nuclei (blue) are stained with DAPI. Caption from a November 26, 2012 news release from U Penn (Penn Medicine).

Lili Guo, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania

View Media

6601: Atomic-level structure of the HIV capsid

6601: Atomic-level structure of the HIV capsid

This animation shows atoms of the HIV capsid, the shell that encloses the virus's genetic material. Scientists determined the exact structure of the capsid using a variety of imaging techniques and analyses. They then entered this data into a supercomputer to produce this image. Related to image 3477.

Juan R. Perilla and the Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

View Media

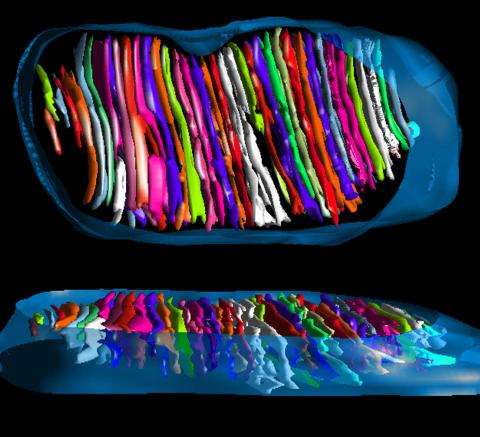

3662: Mitochondrion from insect flight muscle

3662: Mitochondrion from insect flight muscle

This is a tomographic reconstruction of a mitochondrion from an insect flight muscle. Mitochondria are cellular compartments that are best known as the powerhouses that convert energy from the food into energy that runs a range of biological processes. Nearly all our cells have mitochondria.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media

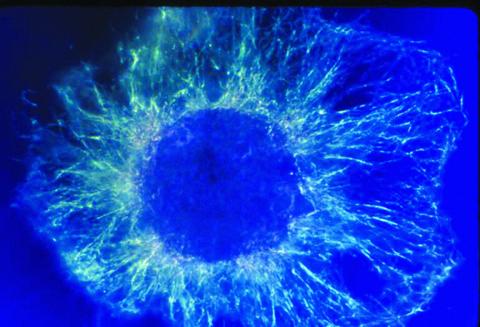

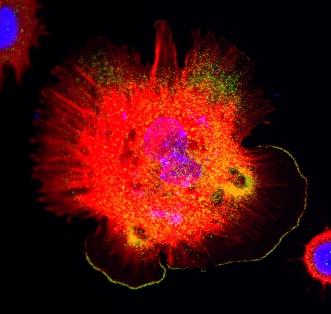

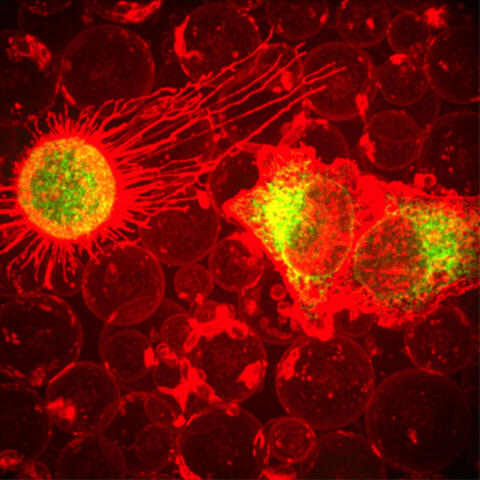

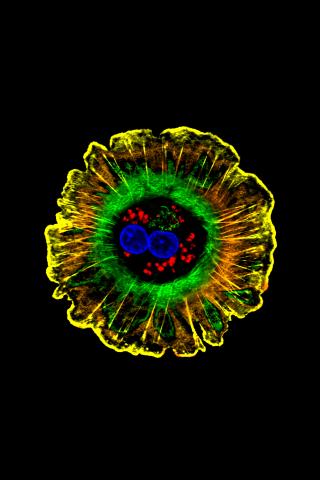

3328: Spreading Cells 01

3328: Spreading Cells 01

Cells move forward with lamellipodia and filopodia supported by networks and bundles of actin filaments. Proper, controlled cell movement is a complex process. Recent research has shown that an actin-polymerizing factor called the Arp2/3 complex is the key component of the actin polymerization engine that drives amoeboid cell motility. ARPC3, a component of the Arp2/3 complex, plays a critical role in actin nucleation. In this photo, the ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells were fixed and stained with Alexa 546 phalloidin for F-actin (red), Arp2 (green), and DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). Arp2, a subunit of the Arp2/3 complex, is localized at the lamellipodia leading edge of ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells. Related to images 3329, 3330, 3331, 3332, and 3333.

Rong Li and Praveen Suraneni, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

View Media

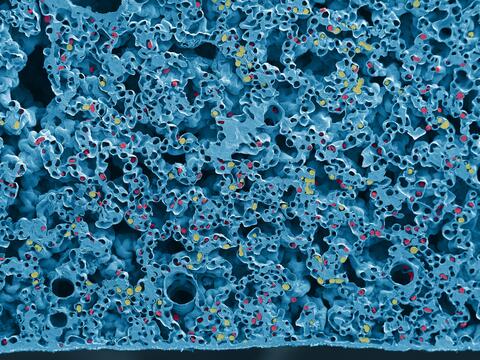

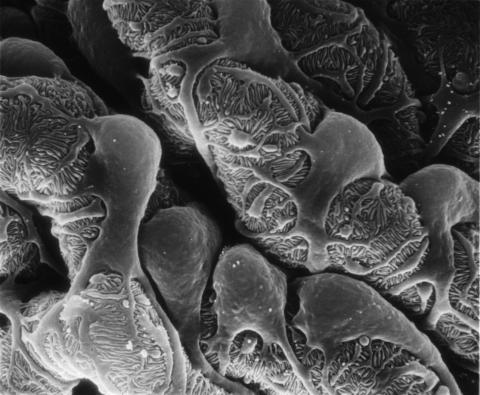

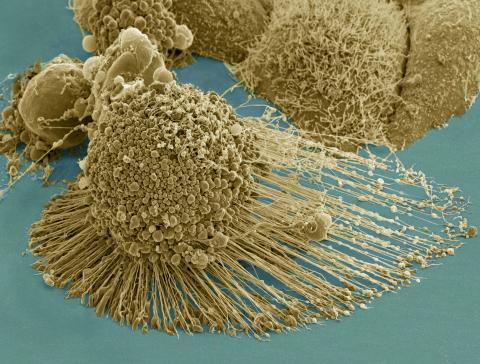

3565: Podocytes from a chronically diseased kidney

3565: Podocytes from a chronically diseased kidney

This scanning electron microscope (SEM) image shows podocytes--cells in the kidney that play a vital role in filtering waste from the bloodstream--from a patient with chronic kidney disease. This image first appeared in Princeton Journal Watch on October 4, 2013.

Olga Troyanskaya, Princeton University and Matthias Kretzler, University of Michigan

View Media

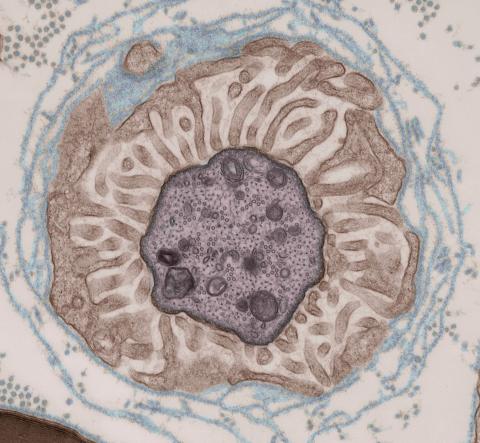

3740: Transmission electron microscopy showing cross-section of the node of Ranvier

3740: Transmission electron microscopy showing cross-section of the node of Ranvier

Nodes of Ranvier are short gaps in the myelin sheath surrounding myelinated nerve cells (axons). Myelin insulates axons, and the node of Ranvier is where the axon is exposed to the extracellular environment, allowing for the transmission of action potentials at these nodes via ion flows between the inside and outside of the axon. The image shows a cross-section through the node, with the surrounding extracellular matrix encasing and supporting the axon shown in cyan.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

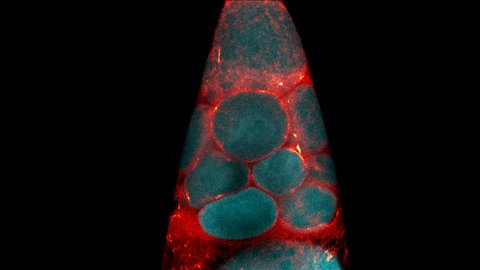

5887: Plasma-Derived Membrane Vesicles

5887: Plasma-Derived Membrane Vesicles

This fiery image doesn’t come from inside a bubbling volcano. Instead, it shows animal cells caught in the act of making bubbles, or blebbing. Some cells regularly pinch off parts of their membranes to produce bubbles filled with a mix of proteins and fats. The bubbles (red) are called plasma-derived membrane vesicles, or PMVs, and can travel to other parts of the body where they may aid in cell-cell communication. The University of Texas, Austin, researchers responsible for this photo are exploring ways to use PMVs to deliver medicines to precise locations in the body.

This image, entered in the Biophysical Society’s 2017 Art of Science Image contest, used two-channel spinning disk confocal fluorescence microscopy. It was also featured in the NIH Director’s Blog in May 2017.

This image, entered in the Biophysical Society’s 2017 Art of Science Image contest, used two-channel spinning disk confocal fluorescence microscopy. It was also featured in the NIH Director’s Blog in May 2017.

Jeanne Stachowiak, University of Texas at Austin

View Media

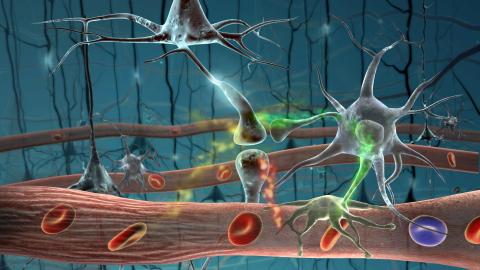

2323: Motion in the brain

2323: Motion in the brain

Amid a network of blood vessels and star-shaped support cells, neurons in the brain signal each other. The mists of color show the flow of important molecules like glucose and oxygen. This image is a snapshot from a 52-second simulation created by an animation artist. Such visualizations make biological processes more accessible and easier to understand.

Kim Hager and Neal Prakash, University of California, Los Angeles

View Media

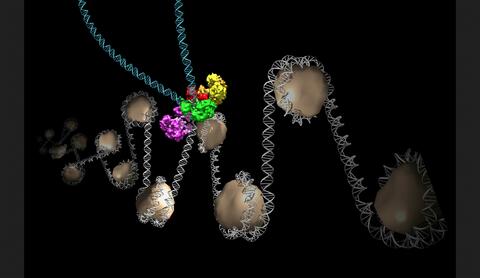

6346: Intasome

6346: Intasome

Salk researchers captured the structure of a protein complex called an intasome (center) that lets viruses similar to HIV establish permanent infection in their hosts. The intasome hijacks host genomic material, DNA (white) and histones (beige), and irreversibly inserts viral DNA (blue). The image was created by Jamie Simon and Dmitry Lyumkis. Work that led to the 3D map was published in: Ballandras-Colas A, Brown M, Cook NJ, Dewdney TG, Demeler B, Cherepanov P, Lyumkis D, & Engelman AN. (2016). Cryo-EM reveals a novel octameric integrase structure for ?-retroviral intasome function. Nature, 530(7590), 358—361

National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy http://nramm.nysbc.org/nramm-images/ Source: Bridget Carragher

View Media

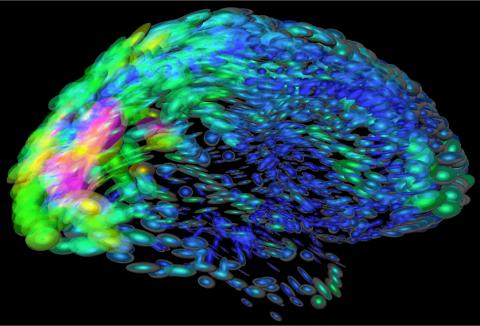

2419: Mapping brain differences

2419: Mapping brain differences

This image of the human brain uses colors and shapes to show neurological differences between two people. The blurred front portion of the brain, associated with complex thought, varies most between the individuals. The blue ovals mark areas of basic function that vary relatively little. Visualizations like this one are part of a project to map complex and dynamic information about the human brain, including genes, enzymes, disease states, and anatomy. The brain maps represent collaborations between neuroscientists and experts in math, statistics, computer science, bioinformatics, imaging, and nanotechnology.

Arthur Toga, University of California, Los Angeles

View Media

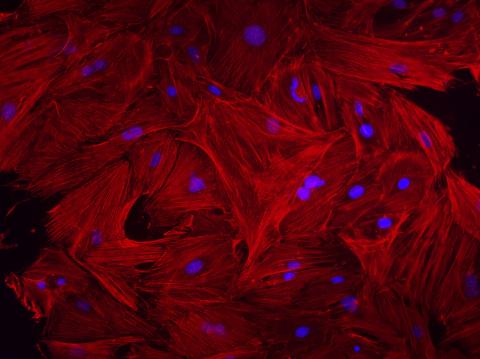

3281: Mouse heart fibroblasts

3281: Mouse heart fibroblasts

This image shows mouse fetal heart fibroblast cells. The muscle protein actin is stained red, and the cell nuclei are stained blue. The image was part of a study investigating stem cell-based approaches to repairing tissue damage after a heart attack. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Kara McCloskey lab, University of California, Merced, via CIRM

View Media

3486: Apoptosis reversed

3486: Apoptosis reversed

Two healthy cells (bottom, left) enter into apoptosis (bottom, center) but spring back to life after a fatal toxin is removed (bottom, right; top).

Hogan Tang of the Denise Montell Lab, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

View Media

3603: Salivary gland in the developing fruit fly

3603: Salivary gland in the developing fruit fly

For fruit flies, the salivary gland is used to secrete materials for making the pupal case, the protective enclosure in which a larva transforms into an adult fly. For scientists, this gland provided one of the earliest glimpses into the genetic differences between individuals within a species. Chromosomes in the cells of these salivary glands replicate thousands of times without dividing, becoming so huge that scientists can easily view them under a microscope and see differences in genetic content between individuals.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Richard Fehon, University of Chicago

View Media

2324: Movements of myosin

2324: Movements of myosin

Inside the fertilized egg cell of a fruit fly, we see a type of myosin (related to the protein that helps muscles contract) made to glow by attaching a fluorescent protein. After fertilization, the myosin proteins are distributed relatively evenly near the surface of the embryo. The proteins temporarily vanish each time the cells' nuclei--initially buried deep in the cytoplasm--divide. When the multiplying nuclei move to the surface, they shift the myosin, producing darkened holes. The glowing myosin proteins then gather, contract, and start separating the nuclei into their own compartments.

Victoria Foe, University of Washington

View Media

6754: Fruit fly nurse cells transporting their contents during egg development

6754: Fruit fly nurse cells transporting their contents during egg development

In many animals, the egg cell develops alongside sister cells. These sister cells are called nurse cells in the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), and their job is to “nurse” an immature egg cell, or oocyte. Toward the end of oocyte development, the nurse cells transfer all their contents into the oocyte in a process called nurse cell dumping. This video captures this transfer, showing significant shape changes on the part of the nurse cells (blue), which are powered by wavelike activity of the protein myosin (red). Researchers created the video using a confocal laser scanning microscope. Related to image 6753.

Adam C. Martin, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

View Media

6547: Cell Nucleus and Lipid Droplets

6547: Cell Nucleus and Lipid Droplets

A cell nucleus (blue) surrounded by lipid droplets (yellow). Exogenously expressed, S-tagged UBXD8 (green) recruits endogenous p97/VCP (red) to the surface of lipid droplets in oleate-treated HeLa cells. Nucleus stained with DAPI.

James Olzmann, University of California, Berkeley

View Media

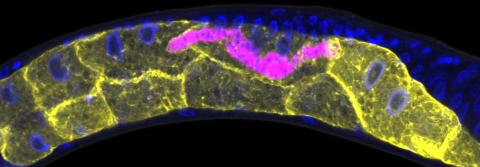

5777: Microsporidia in roundworm 1

5777: Microsporidia in roundworm 1

Many disease-causing microbes manipulate their host’s metabolism and cells for their own ends. Microsporidia—which are parasites closely related to fungi—infect and multiply inside animal cells, and take the rearranging of cells’ interiors to a new level. They reprogram animal cells such that the cells start to fuse, causing them to form long, continuous tubes. As shown in this image of the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, microsporidia (shown in magenta) have invaded the worm’s gut cells (shown in yellow; the cells’ nuclei are shown in blue) and have instructed the cells to merge. The cell fusion enables the microsporidia to thrive and propagate in the expanded space. Scientists study microsporidia in worms to gain more insight into how these parasites manipulate their host cells. This knowledge might help researchers devise strategies to prevent or treat infections with microsporidia. For more on the research into microsporidia, see this news release from the University of California San Diego. Related to images 5778 and 5779.

Keir Balla and Emily Troemel, University of California San Diego

View Media

6556: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 72 hour

6556: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 72 hour

Floral pattern emerging as two bacterial species, motile Acinetobacter baylyi and non-motile Escherichia coli (green), are grown together for 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface from a small inoculum in the center of a Petri dish.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6553 for a photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6555 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6553 for a photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6555 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

L. Xiong et al, eLife 2020;9: e48885

View Media

3497: Wound healing in process

3497: Wound healing in process

Wound healing requires the action of stem cells. In mice that lack the Sept2/ARTS gene, stem cells involved in wound healing live longer and wounds heal faster and more thoroughly than in normal mice. This confocal microscopy image from a mouse lacking the Sept2/ARTS gene shows a tail wound in the process of healing. See more information in the article in Science.

Related to images 3498 and 3500.

Related to images 3498 and 3500.

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

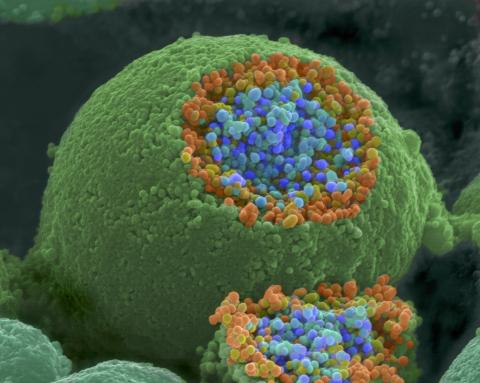

1244: Nerve ending

1244: Nerve ending

A scanning electron microscope picture of a nerve ending. It has been broken open to reveal vesicles (orange and blue) containing chemicals used to pass messages in the nervous system.

Tina Weatherby Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

View Media

3519: HeLa cells

3519: HeLa cells

Scanning electron micrograph of an apoptotic HeLa cell. Zeiss Merlin HR-SEM. See related images 3518, 3520, 3521, 3522.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media

3786: Movie of in vitro assembly of a cell-signaling pathway

3786: Movie of in vitro assembly of a cell-signaling pathway

T cells are white blood cells that are important in defending the body against bacteria, viruses and other pathogens. Each T cell carries proteins, called T-cell receptors, on its surface that are activated when they come in contact with an invader. This activation sets in motion a cascade of biochemical changes inside the T cell to mount a defense against the invasion. Scientists have been interested for some time what happens after a T-cell receptor is activated. One obstacle has been to study how this signaling cascade, or pathway, proceeds inside T cells.

In this video, researchers have created a T-cell receptor pathway consisting of 12 proteins outside the cell on an artificial membrane. The video shows three key steps during the signaling process: phosphorylation of the T-cell receptor (green), clustering of a protein called linker for activation of T cells (LAT) (blue) and polymerization of the cytoskeleton protein actin (red). The findings show that the T-cell receptor signaling proteins self-organize into separate physical and biochemical compartments. This new system of studying molecular pathways outside the cells will enable scientists to better understand how the immune system combats microbes or other agents that cause infection.

To learn more how researchers assembled this T-cell receptor pathway, see this press release from HHMI's Marine Biological Laboratory Whitman Center. Related to image 3787.

In this video, researchers have created a T-cell receptor pathway consisting of 12 proteins outside the cell on an artificial membrane. The video shows three key steps during the signaling process: phosphorylation of the T-cell receptor (green), clustering of a protein called linker for activation of T cells (LAT) (blue) and polymerization of the cytoskeleton protein actin (red). The findings show that the T-cell receptor signaling proteins self-organize into separate physical and biochemical compartments. This new system of studying molecular pathways outside the cells will enable scientists to better understand how the immune system combats microbes or other agents that cause infection.

To learn more how researchers assembled this T-cell receptor pathway, see this press release from HHMI's Marine Biological Laboratory Whitman Center. Related to image 3787.

Xiaolei Su, HHMI Whitman Center of the Marine Biological Laboratory

View Media

5760: Annotated TEM cross-section of C. elegans (roundworm)

5760: Annotated TEM cross-section of C. elegans (roundworm)

The worm Caenorhabditis elegans is a popular laboratory animal because its small size and fairly simple body make it easy to study. Scientists use this small worm to answer many research questions in developmental biology, neurobiology, and genetics. This image, which was taken with transmission electron microscopy (TEM), shows a cross-section through C. elegans, revealing various internal structures labeled in the image. You can find a high-resolution image without the annotations at image 5759.

The image is from a figure in an article published in the journal eLife.

The image is from a figure in an article published in the journal eLife.

Piali Sengupta, Brandeis University

View Media

3610: Human liver cell (hepatocyte)

3610: Human liver cell (hepatocyte)

Hepatocytes, like the one shown here, are the most abundant type of cell in the human liver. They play an important role in building proteins; producing bile, a liquid that aids in digesting fats; and chemically processing molecules found normally in the body, like hormones, as well as foreign substances like medicines and alcohol.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Donna Beer Stolz, University of Pittsburgh

View Media

6985: Fruit fly brain responds to adipokines

6985: Fruit fly brain responds to adipokines

Drosophila adult brain showing that an adipokine (fat hormone) generates a response from neurons (aqua) and regulates insulin-producing neurons (red).

Related to images 6982, 6983, and 6984.

Related to images 6982, 6983, and 6984.

Akhila Rajan, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center

View Media

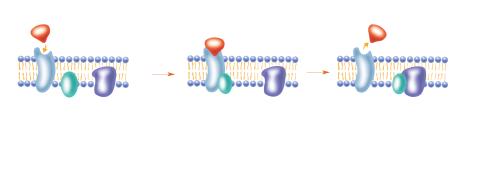

2536: G switch

2536: G switch

The G switch allows our bodies to respond rapidly to hormones. See images 2537 and 2538 for labeled versions of this image. Featured in Medicines By Design.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

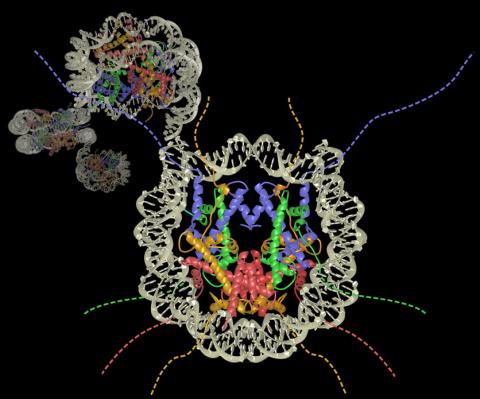

2741: Nucleosome

2741: Nucleosome

Like a strand of white pearls, DNA wraps around an assembly of special proteins called histones (colored) to form the nucleosome, a structure responsible for regulating genes and condensing DNA strands to fit into the cell's nucleus. Researchers once thought that nucleosomes regulated gene activity through their histone tails (dotted lines), but a 2010 study revealed that the structures' core also plays a role. The finding sheds light on how gene expression is regulated and how abnormal gene regulation can lead to cancer.

Karolin Luger, Colorado State University

View Media

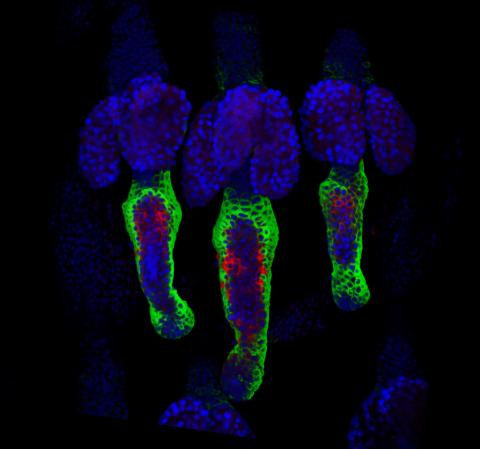

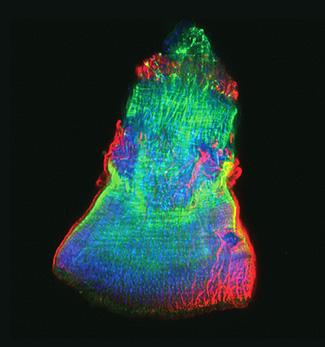

3593: Isolated Planarian Pharynx

3593: Isolated Planarian Pharynx

The feeding tube, or pharynx, of a planarian worm with cilia shown in red and muscle fibers shown in green

View Media

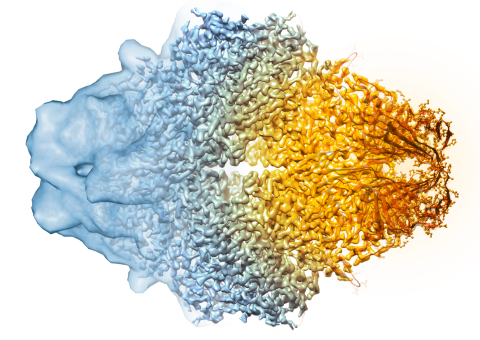

5882: Beta-galactosidase montage showing cryo-EM improvement--transparent background

5882: Beta-galactosidase montage showing cryo-EM improvement--transparent background

Composite image of beta-galactosidase showing how cryo-EM’s resolution has improved dramatically in recent years. Older images to the left, more recent to the right. Related to image 5883. NIH Director Francis Collins featured this on his blog on January 14, 2016.

Veronica Falconieri, Sriram Subramaniam Lab, National Cancer Institute

View Media

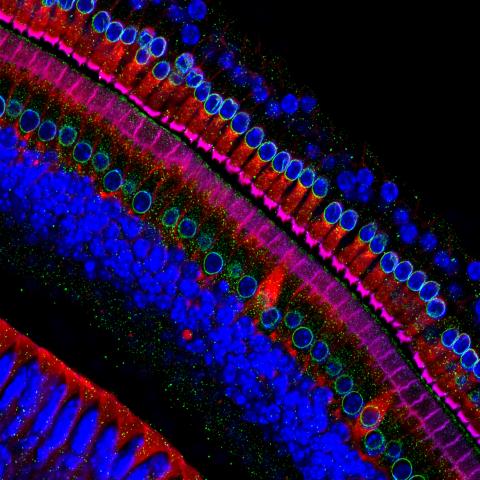

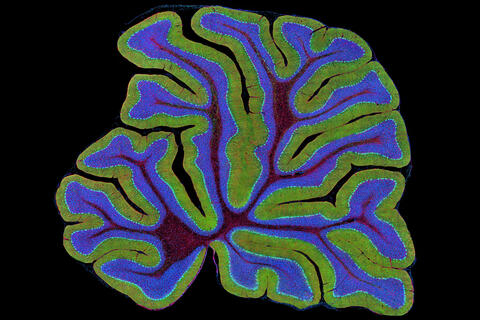

3723: Fluorescent microscopy of kidney tissue

3723: Fluorescent microscopy of kidney tissue

Serum albumin (SA) is the most abundant protein in the blood plasma of mammals. SA has a characteristic heart-shape structure and is a highly versatile protein. It helps maintain normal water levels in our tissues and carries almost half of all calcium ions in human blood. SA also transports some hormones, nutrients and metals throughout the bloodstream. Despite being very similar to our own SA, those from other animals can cause some mild allergies in people. Therefore, some scientists study SAs from humans and other mammals to learn more about what subtle structural or other differences cause immune responses in the body.

Related to entries 3725 and 3675.

Related to entries 3725 and 3675.

Tom Deerinck , National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media