Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

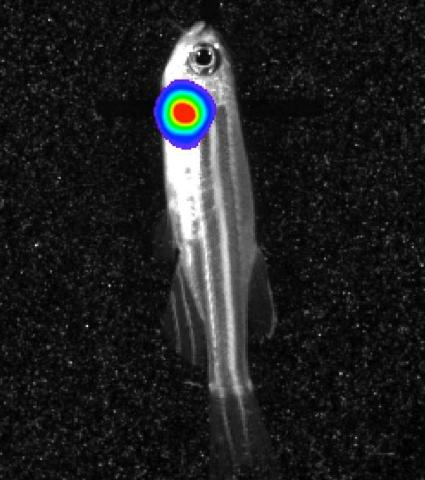

3558: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish - lateral view

3558: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish - lateral view

Luciferase-based imaging enables visualization and quantification of internal organs and transplanted cells in live adult zebrafish. In this image, a cardiac muscle-restricted promoter drives firefly luciferase expression (lateral view).

For imagery of both the lateral and overhead view go to 3556.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For more information about the illumated area go to 3559.

For imagery of both the lateral and overhead view go to 3556.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For more information about the illumated area go to 3559.

Kenneth Poss, Duke University

View Media

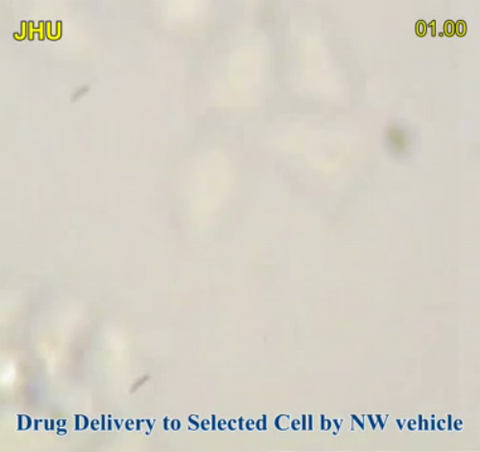

3779: Precisely Delivering Chemical Cargo to Cells

3779: Precisely Delivering Chemical Cargo to Cells

Moving protein or other molecules to specific cells to treat or examine them has been a major biological challenge. Scientists have now developed a technique for delivering chemicals to individual cells. The approach involves gold nanowires that, for example, can carry tumor-killing proteins. The advance was possible after researchers developed electric tweezers that could manipulate gold nanowires to help deliver drugs to single cells.

This movie shows the manipulation of the nanowires for drug delivery to a single cell. To learn more about this technique, see this post in the Computing Life series.

This movie shows the manipulation of the nanowires for drug delivery to a single cell. To learn more about this technique, see this post in the Computing Life series.

Nature Nanotechnology

View Media

6538: Pathways: The Fascinating Cells of Research Organisms

6538: Pathways: The Fascinating Cells of Research Organisms

Learn how research organisms, such as fruit flies and mice, can help us understand and treat human diseases. Discover more resources from NIGMS’ Pathways collaboration with Scholastic. View the video on YouTube for closed captioning.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

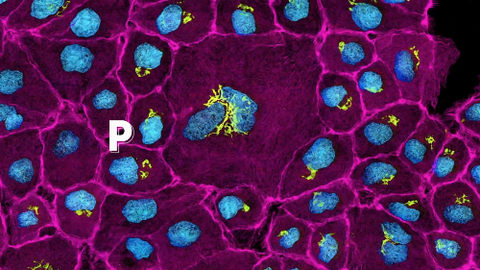

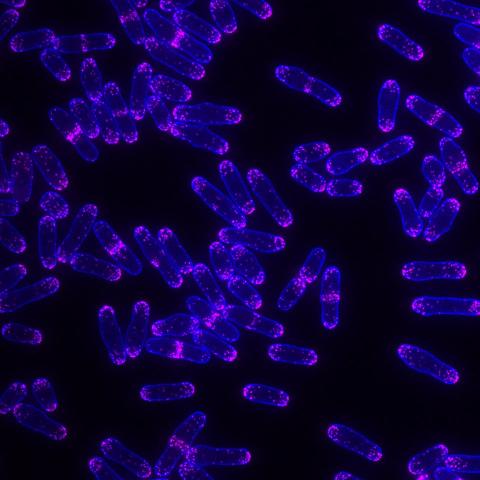

6794: Yeast cells with Fimbrin Fim1

6794: Yeast cells with Fimbrin Fim1

Yeast cells with the protein Fimbrin Fim1 shown in magenta. This protein plays a role in cell division. This image was captured using wide-field microscopy with deconvolution.

Related to images 6791, 6792, 6793, 6797, 6798, and videos 6795 and 6796.

Related to images 6791, 6792, 6793, 6797, 6798, and videos 6795 and 6796.

Alaina Willet, Kathy Gould’s lab, Vanderbilt University.

View Media

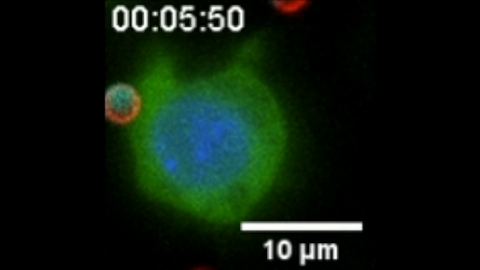

6801: “Two-faced” Janus particle activating a macrophage

6801: “Two-faced” Janus particle activating a macrophage

A macrophage—a type of immune cell that engulfs invaders—“eats” and is activated by a “two-faced” Janus particle. The particle is called “two-faced” because each of its two hemispheres is coated with a different type of molecule, shown here in red and cyan. During macrophage activation, a transcription factor tagged with a green fluorescence protein (NF-κB) gradually moves from the cell’s cytoplasm into its nucleus and causes DNA transcription. The distribution of molecules on “two-faced” Janus particles can be altered to control the activation of immune cells. Details on this “geometric manipulation” strategy can be found in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences paper "Geometrical reorganization of Dectin-1 and TLR2 on single phagosomes alters their synergistic immune signaling" by Li et al. and the Scientific Reports paper "Spatial organization of FcγR and TLR2/1 on phagosome membranes differentially regulates their synergistic and inhibitory receptor crosstalk" by Li et al. This video was captured using epi-fluorescence microscopy.

Related to video 6800.

Related to video 6800.

Yan Yu, Indiana University, Bloomington.

View Media

5764: Host infection stimulates antibiotic resistance

5764: Host infection stimulates antibiotic resistance

This illustration shows pathogenic bacteria behave like a Trojan horse: switching from antibiotic susceptibility to resistance during infection. Salmonella are vulnerable to antibiotics while circulating in the blood (depicted by fire on red blood cell) but are highly resistant when residing within host macrophages. This leads to treatment failure with the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria.

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call, and the research was funded in part by NIGMS.

View Media

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call, and the research was funded in part by NIGMS.

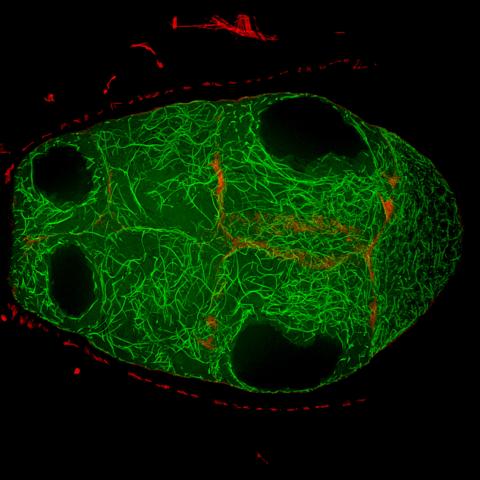

6811: Fruit fly egg chamber

6811: Fruit fly egg chamber

A fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) egg chamber with microtubules shown in green and actin filaments shown in red. Egg chambers are multicellular structures in fruit flies ovaries that each give rise to a single egg. Microtubules and actin filaments give the chambers structure and shape. This image was captured using a confocal microscope.

More information on the research that produced this image can be found in the Current Biology paper "Gatekeeper function for Short stop at the ring canals of the Drosophila ovary" by Lu et al.

More information on the research that produced this image can be found in the Current Biology paper "Gatekeeper function for Short stop at the ring canals of the Drosophila ovary" by Lu et al.

Vladimir I. Gelfand, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University.

View Media

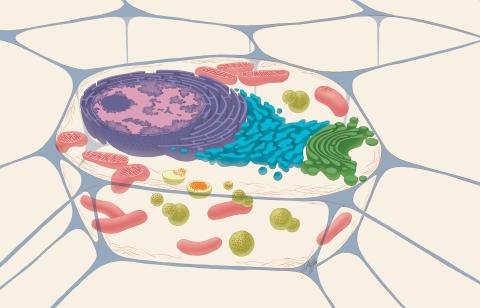

1274: Animal cell

1274: Animal cell

A typical animal cell, sliced open to reveal a cross-section of organelles.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

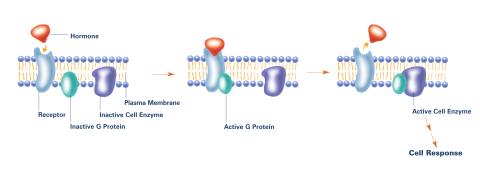

2537: G switch (with labels)

2537: G switch (with labels)

The G switch allows our bodies to respond rapidly to hormones. G proteins act like relay batons to pass messages from circulating hormones into cells. A hormone (red) encounters a receptor (blue) in the membrane of a cell. Next, a G protein (green) becomes activated and makes contact with the receptor to which the hormone is attached. Finally, the G protein passes the hormone's message to the cell by switching on a cell enzyme (purple) that triggers a response. See image 2536 and 2538 for other versions of this image. Featured in Medicines By Design.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

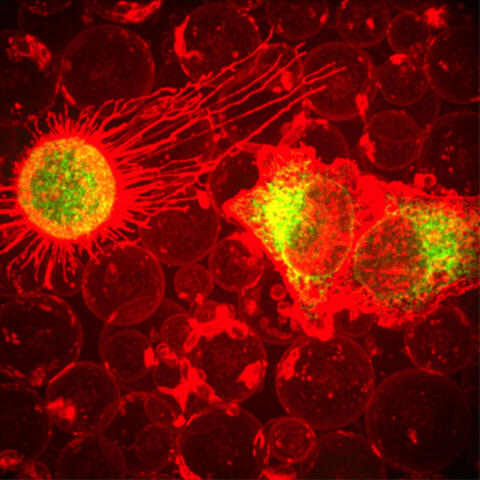

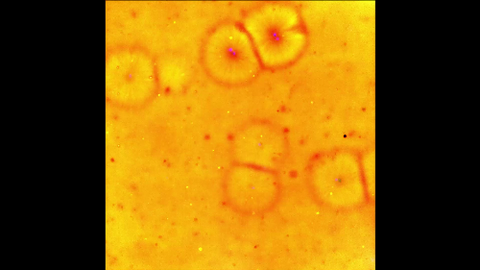

5887: Plasma-Derived Membrane Vesicles

5887: Plasma-Derived Membrane Vesicles

This fiery image doesn’t come from inside a bubbling volcano. Instead, it shows animal cells caught in the act of making bubbles, or blebbing. Some cells regularly pinch off parts of their membranes to produce bubbles filled with a mix of proteins and fats. The bubbles (red) are called plasma-derived membrane vesicles, or PMVs, and can travel to other parts of the body where they may aid in cell-cell communication. The University of Texas, Austin, researchers responsible for this photo are exploring ways to use PMVs to deliver medicines to precise locations in the body.

This image, entered in the Biophysical Society’s 2017 Art of Science Image contest, used two-channel spinning disk confocal fluorescence microscopy. It was also featured in the NIH Director’s Blog in May 2017.

This image, entered in the Biophysical Society’s 2017 Art of Science Image contest, used two-channel spinning disk confocal fluorescence microscopy. It was also featured in the NIH Director’s Blog in May 2017.

Jeanne Stachowiak, University of Texas at Austin

View Media

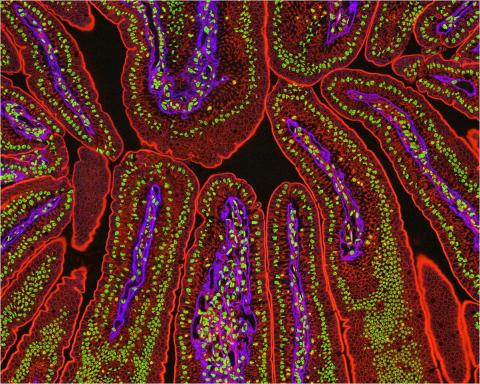

3390: NCMIR Intestine-2

3390: NCMIR Intestine-2

The small intestine is where most of our nutrients from the food we eat are absorbed into the bloodstream. The walls of the intestine contain small finger-like projections called villi which increase the organ's surface area, enhancing nutrient absorption. It consists of the duodenum, which connects to the stomach, the jejenum and the ileum, which connects with the large intestine. Related to image 3389.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

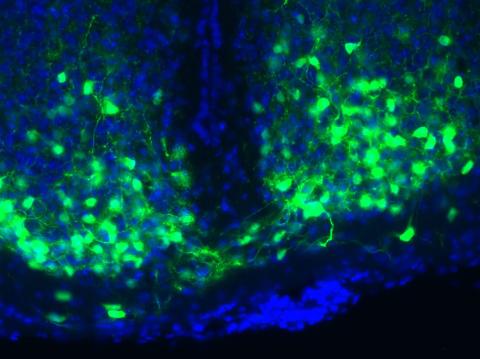

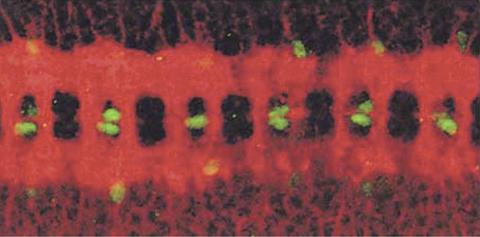

3547: Master clock of the mouse brain

3547: Master clock of the mouse brain

An image of the area of the mouse brain that serves as the 'master clock,' which houses the brain's time-keeping neurons. The nuclei of the clock cells are shown in blue. A small molecule called VIP, shown in green, enables neurons in the central clock in the mammalian brain to synchronize.

Erik Herzog, Washington University in St. Louis

View Media

2439: Hydra 03

2439: Hydra 03

Hydra magnipapillata is an invertebrate animal used as a model organism to study developmental questions, for example the formation of the body axis.

Hiroshi Shimizu, National Institute of Genetics in Mishima, Japan

View Media

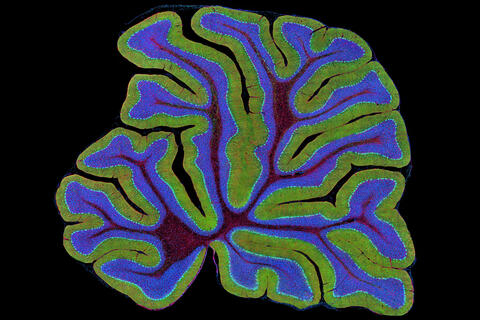

3639: Cerebellum: the brain's locomotion control center

3639: Cerebellum: the brain's locomotion control center

The cerebellum of a mouse is shown here in cross-section. The cerebellum is the brain's locomotion control center. Every time you shoot a basketball, tie your shoe or chop an onion, your cerebellum fires into action. Found at the base of your brain, the cerebellum is a single layer of tissue with deep folds like an accordion. People with damage to this region of the brain often have difficulty with balance, coordination and fine motor skills. For a higher magnification, see image 3371.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Thomas Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research, University of California, San Diego

View Media

6982: Insulin production and fat sensing in fruit flies

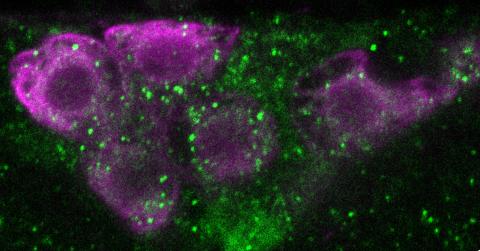

6982: Insulin production and fat sensing in fruit flies

Fourteen neurons (magenta) in the adult Drosophila brain produce insulin, and fat tissue sends packets of lipids to the brain via the lipoprotein carriers (green). This image was captured using a confocal microscope and shows a maximum intensity projection of many slices.

Related to images 6983, 6984, and 6985.

Related to images 6983, 6984, and 6985.

Akhila Rajan, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center

View Media

2429: Highlighted cells

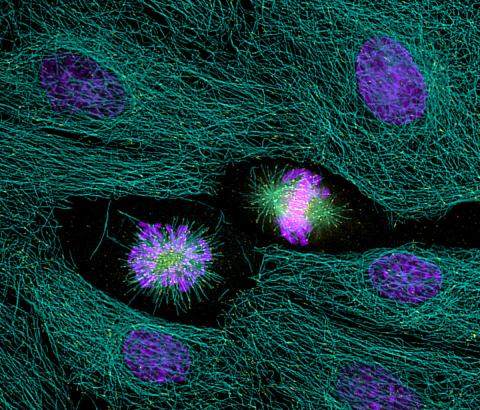

2429: Highlighted cells

The cytoskeleton (green) and DNA (purple) are highlighed in these cells by immunofluorescence.

Torsten Wittmann, Scripps Research Institute

View Media

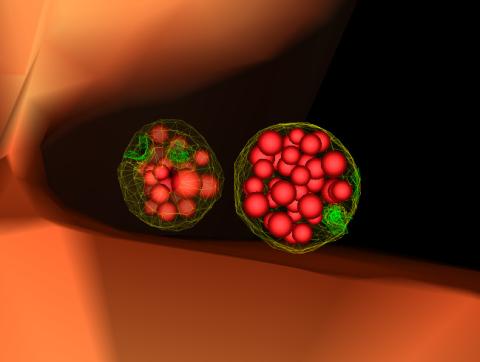

5767: Multivesicular bodies containing intralumenal vesicles assemble at the vacuole 3

5767: Multivesicular bodies containing intralumenal vesicles assemble at the vacuole 3

Collecting and transporting cellular waste and sorting it into recylable and nonrecylable pieces is a complex business in the cell. One key player in that process is the endosome, which helps collect, sort and transport worn-out or leftover proteins with the help of a protein assembly called the endosomal sorting complexes for transport (or ESCRT for short). These complexes help package proteins marked for breakdown into intralumenal vesicles, which, in turn, are enclosed in multivesicular bodies for transport to the places where the proteins are recycled or dumped. In this image, two multivesicular bodies (with yellow membranes) contain tiny intralumenal vesicles (with a diameter of only 25 nanometers; shown in red) adjacent to the cell's vacuole (in orange).

Scientists working with baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) study the budding inward of the limiting membrane (green lines on top of the yellow lines) into the intralumenal vesicles. This tomogram was shot with a Tecnai F-20 high-energy electron microscope, at 29,000x magnification, with a 0.7-nm pixel, ~4-nm resolution.

To learn more about endosomes, see the Biomedical Beat blog post The Cell’s Mailroom. Related to a microscopy photograph 5768 that was used to generate this illustration and a zoomed-out version 5769 of this illustration.

Scientists working with baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) study the budding inward of the limiting membrane (green lines on top of the yellow lines) into the intralumenal vesicles. This tomogram was shot with a Tecnai F-20 high-energy electron microscope, at 29,000x magnification, with a 0.7-nm pixel, ~4-nm resolution.

To learn more about endosomes, see the Biomedical Beat blog post The Cell’s Mailroom. Related to a microscopy photograph 5768 that was used to generate this illustration and a zoomed-out version 5769 of this illustration.

Matthew West and Greg Odorizzi, University of Colorado

View Media

6588: Cell-like compartments emerging from scrambled frog eggs 2

6588: Cell-like compartments emerging from scrambled frog eggs 2

Cell-like compartments spontaneously emerge from scrambled frog eggs, with nuclei (blue) from frog sperm. Endoplasmic reticulum (red) and microtubules (green) are also visible. Regions without nuclei formed smaller compartments. Video created using epifluorescence microscopy.

For more photos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6584, 6585, 6586, 6591, 6592, and 6593.

For videos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6587, 6589, and 6590.

Xianrui Cheng, Stanford University School of Medicine.

View Media

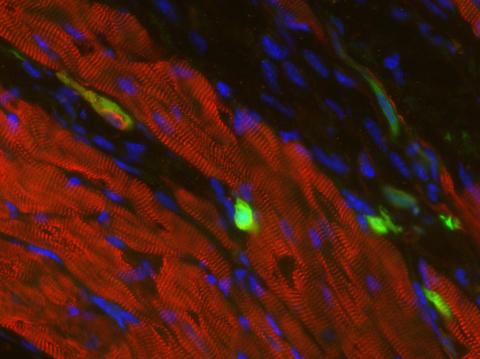

3273: Heart muscle with reprogrammed skin cells

3273: Heart muscle with reprogrammed skin cells

Skins cells were reprogrammed into heart muscle cells. The cells highlighted in green are remaining skin cells. Red indicates a protein that is unique to heart muscle. The technique used to reprogram the skin cells into heart cells could one day be used to mend heart muscle damaged by disease or heart attack. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Deepak Srivastava, Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, via CIRM

View Media

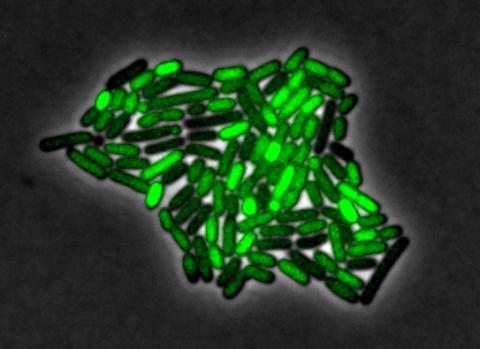

3253: Pulsating response to stress in bacteria

3253: Pulsating response to stress in bacteria

By attaching fluorescent proteins to the genetic circuit responsible for B. subtilis's stress response, researchers can observe the cells' pulses as green flashes. In response to a stressful environment like one lacking food, B. subtilis activates a large set of genes that help it respond to the hardship. Instead of leaving those genes on as previously thought, researchers discovered that the bacteria flip the genes on and off, increasing the frequency of these pulses with increasing stress. See entry 3254 for the related video.

Michael Elowitz, Caltech University

View Media

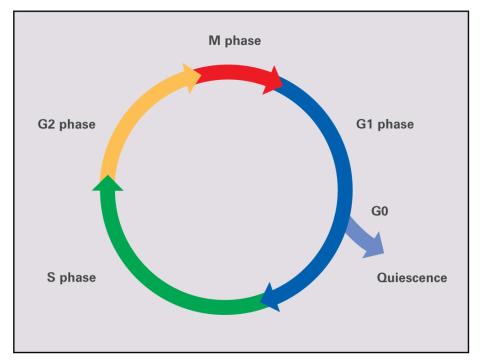

2499: Cell cycle (with labels)

2499: Cell cycle (with labels)

Cells progress through a cycle that consists of phases for growth (G1, S, and G2) and division (M). Cells become quiescent when they exit this cycle (G0). See image 2498 for an unlabeled version of this illustration.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

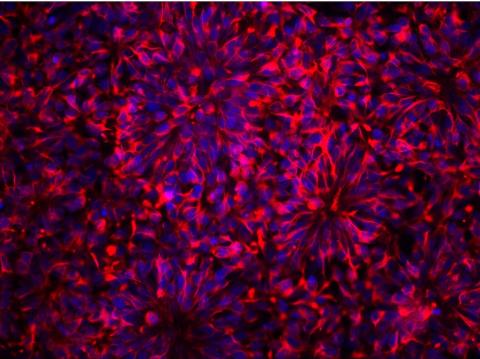

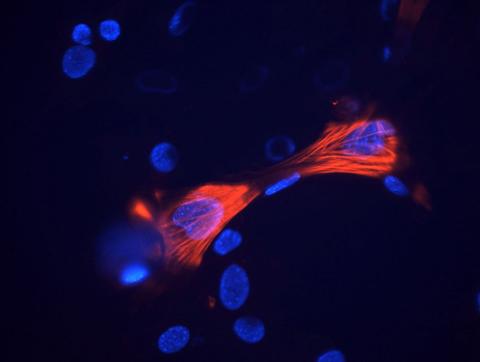

3284: Neurons from human ES cells

3284: Neurons from human ES cells

These neural precursor cells were derived from human embryonic stem cells. The neural cell bodies are stained red, and the nuclei are blue. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Xianmin Zeng lab, Buck Institute for Age Research, via CIRM

View Media

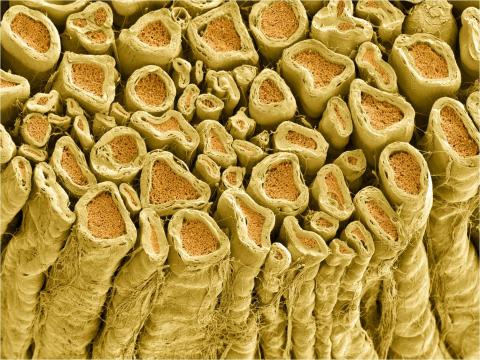

3396: Myelinated axons 1

3396: Myelinated axons 1

Myelinated axons in a rat spinal root. Myelin is a type of fat that forms a sheath around and thus insulates the axon to protect it from losing the electrical current needed to transmit signals along the axon. The axoplasm inside the axon is shown in pink. Related to 3397.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

6750: C. elegans with blue and yellow lights in the background

6750: C. elegans with blue and yellow lights in the background

These microscopic roundworms, called Caenorhabditis elegans, lack eyes and the opsin proteins used by visual systems to detect colors. However, researchers found that the worms can still sense the color of light in a way that enables them to avoid pigmented toxins made by bacteria. This image was captured using a stereo microscope.

H. Robert Horvitz and Dipon Ghosh, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

View Media

3457: Sticky stem cells

3457: Sticky stem cells

Like a group of barnacles hanging onto a rock, these human cells hang onto a matrix coated glass slide. Actin stress fibers, stained magenta, and the protein vinculin, stained green, make this adhesion possible. The fibroblast nuclei are stained blue.

Ankur Singh and Andrés García, Georgia Institute of Technology

View Media

1091: Nerve and glial cells in fruit fly embryo

1091: Nerve and glial cells in fruit fly embryo

Glial cells (stained green) in a fruit fly developing embryo have survived thanks to a signaling pathway initiated by neighboring nerve cells (stained red).

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

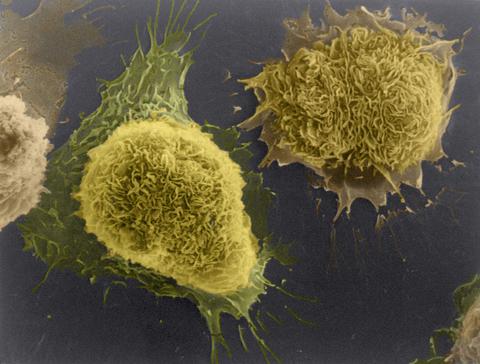

1178: Cultured cells

1178: Cultured cells

This image of laboratory-grown cells was taken with the help of a scanning electron microscope, which yields detailed images of cell surfaces.

Tina Weatherby Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

View Media

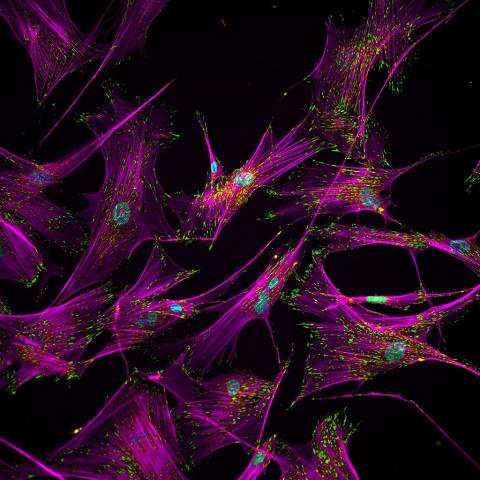

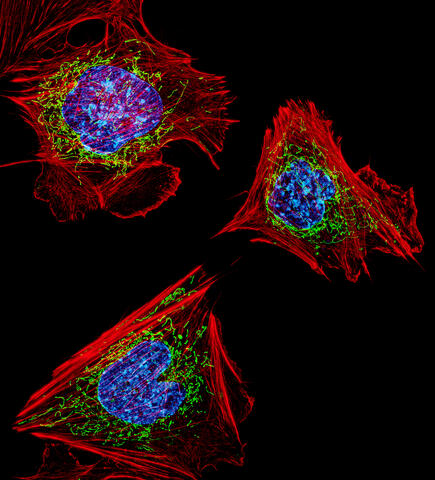

3624: Fibroblasts with nuclei in blue, energy factories in green and the actin cytoskeleton in red

3624: Fibroblasts with nuclei in blue, energy factories in green and the actin cytoskeleton in red

The cells shown here are fibroblasts, one of the most common cells in mammalian connective tissue. These particular cells were taken from a mouse embryo. Scientists used them to test the power of a new microscopy technique that offers vivid views of the inside of a cell. The DNA within the nucleus (blue), mitochondria (green), and actin filaments in the cellular skeleton (red) are clearly visible.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Dylan Burnette, NICHD

View Media

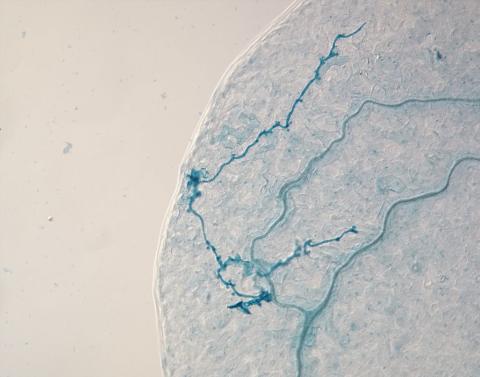

2780: Arabidopsis leaf injected with a pathogen

2780: Arabidopsis leaf injected with a pathogen

This is a magnified view of an Arabidopsis thaliana leaf eight days after being infected with the pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis, which is closely related to crop pathogens that cause 'downy mildew' diseases. It is also more distantly related to the agent that caused the Irish potato famine. The veins of the leaf are light blue; in darker blue are the pathogen's hyphae growing through the leaf. The small round blobs along the length of the hyphae are called haustoria; each is invading a single plant cell to suck nutrients from the cell. Jeff Dangl and other NIGMS-supported researchers investigate how this pathogen and other like it use virulence mechanisms to suppress host defense and help the pathogens grow.

Jeff Dangl, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

3289: Smooth muscle from mouse stem cells

3289: Smooth muscle from mouse stem cells

These smooth muscle cells were derived from mouse neural crest stem cells. Red indicates smooth muscle proteins, blue indicates nuclei. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Deepak Srivastava, Gladstone Institutes, via CIRM

View Media

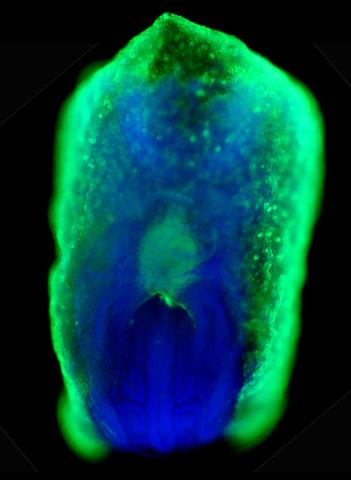

2607: Mouse embryo showing Smad4 protein

2607: Mouse embryo showing Smad4 protein

This eerily glowing blob isn't an alien or a creature from the deep sea--it's a mouse embryo just eight and a half days old. The green shell and core show a protein called Smad4. In the center, Smad4 is telling certain cells to begin forming the mouse's liver and pancreas. Researchers identified a trio of signaling pathways that help switch on Smad4-making genes, starting immature cells on the path to becoming organs. The research could help biologists learn how to grow human liver and pancreas tissue for research, drug testing and regenerative medicine. In addition to NIGMS, NIH's National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases also supported this work.

Kenneth Zaret, Fox Chase Cancer Center

View Media

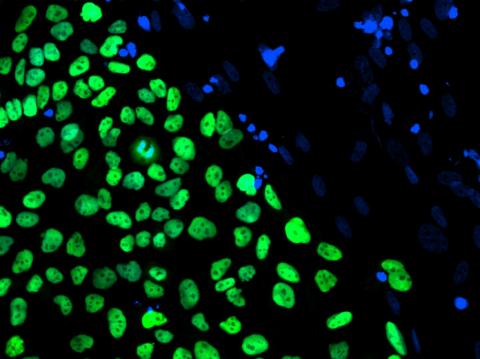

3275: Human embryonic stem cells on feeder cells

3275: Human embryonic stem cells on feeder cells

The nuclei stained green highlight human embryonic stem cells grown under controlled conditions in a laboratory. Blue represents the DNA of surrounding, supportive feeder cells. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. See related image 3724.

Julie Baker lab, Stanford University School of Medicine, via CIRM

View Media

2432: ARTS triggers apoptosis

2432: ARTS triggers apoptosis

Cell showing overproduction of the ARTS protein (red). ARTS triggers apoptosis, as shown by the activation of caspase-3 (green) a key tool in the cell's destruction. The nucleus is shown in blue. Image is featured in October 2015 Biomedical Beat blog post Cool Images: A Halloween-Inspired Cell Collection.

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

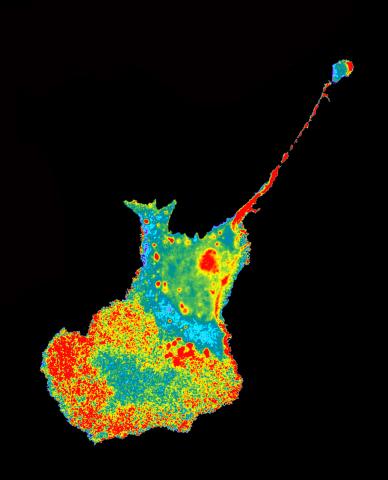

2454: Seeing signaling protein activation in cells 04

2454: Seeing signaling protein activation in cells 04

Cdc42, a member of the Rho family of small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) proteins, regulates multiple cell functions, including motility, proliferation, apoptosis, and cell morphology. In order to fulfill these diverse roles, the timing and location of Cdc42 activation must be tightly controlled. Klaus Hahn and his research group use special dyes designed to report protein conformational changes and interactions, here in living neutrophil cells. Warmer colors in this image indicate higher levels of activation. Cdc42 looks to be activated at cell protrusions.

Related to images 2451, 2452, and 2453.

Related to images 2451, 2452, and 2453.

Klaus Hahn, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Medical School

View Media

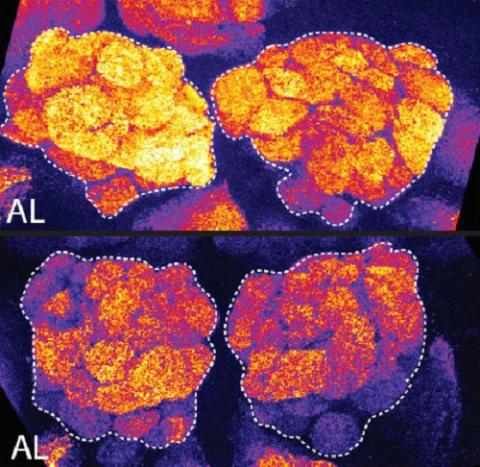

3490: Brains of sleep-deprived and well-rested fruit flies

3490: Brains of sleep-deprived and well-rested fruit flies

On top, the brain of a sleep-deprived fly glows orange because of Bruchpilot, a communication protein between brain cells. These bright orange brain areas are associated with learning. On the bottom, a well-rested fly shows lower levels of Bruchpilot, which might make the fly ready to learn after a good night's rest.

Chiara Cirelli, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

3611: Tiny strands of tubulin, a protein in a cell's skeleton

3611: Tiny strands of tubulin, a protein in a cell's skeleton

Just as our bodies rely on bones for structural support, our cells rely on a cellular skeleton. In addition to helping cells keep their shape, this cytoskeleton transports material within cells and coordinates cell division. One component of the cytoskeleton is a protein called tubulin, shown here as thin strands.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Pakorn Kanchanawong, National University of Singapore and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health; and Clare Waterman, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health

View Media

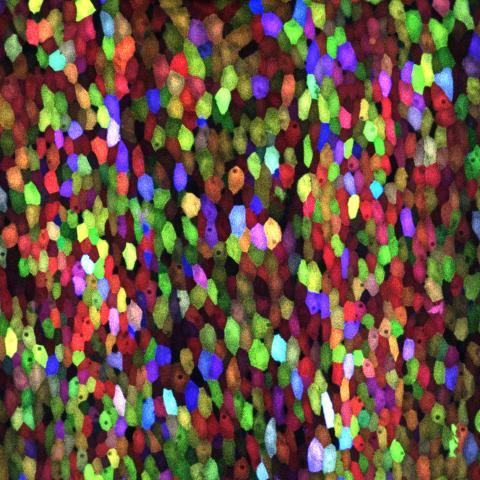

3782: A multicolored fish scale 1

3782: A multicolored fish scale 1

Each of the colored specs in this image is a cell on the surface of a fish scale. To better understand how wounds heal, scientists have inserted genes that make cells brightly glow in different colors into the skin cells of zebrafish, a fish often used in laboratory research. The colors enable the researchers to track each individual cell, for example, as it moves to the location of a cut or scrape over the course of several days. These technicolor fish endowed with glowing skin cells dubbed "skinbow" provide important insight into how tissues recover and regenerate after an injury.

For more information on skinbow fish, see the Biomedical Beat blog post Visualizing Skin Regeneration in Real Time and a press release from Duke University highlighting this research. Related to image 3783.

For more information on skinbow fish, see the Biomedical Beat blog post Visualizing Skin Regeneration in Real Time and a press release from Duke University highlighting this research. Related to image 3783.

Chen-Hui Chen and Kenneth Poss, Duke University

View Media