Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

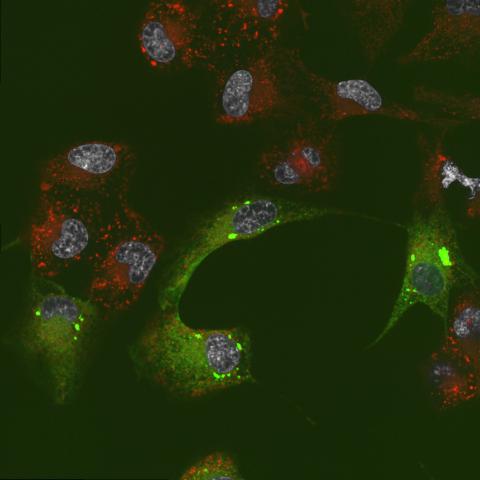

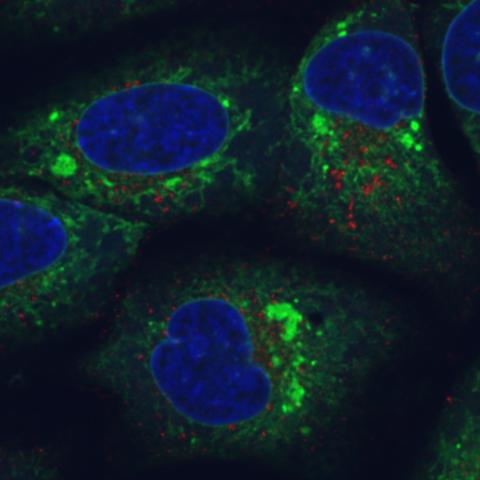

6774: Endoplasmic reticulum abnormalities 2

6774: Endoplasmic reticulum abnormalities 2

Human cells with the gene that codes for the protein FIT2 deleted. After an experimental intervention, they are expressing a nonfunctional version of FIT2, shown in green. The lack of functional FIT2 affected the structure of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and the nonfunctional protein clustered in ER membrane aggregates, seen as large bright-green spots. Lipid droplets are shown in red, and the nucleus is visible in gray. This image was captured using a confocal microscope. Related to image 6773.

Michel Becuwe, Harvard University.

View Media

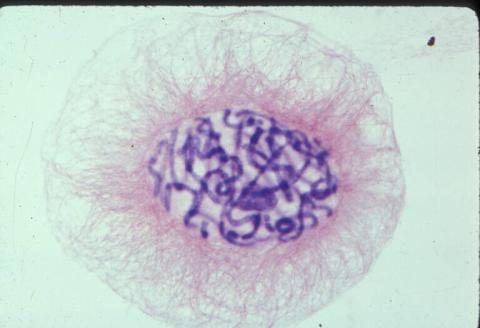

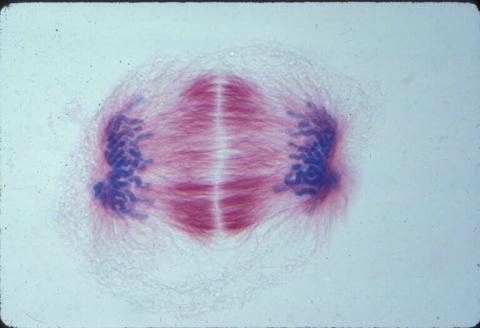

1014: Lily mitosis 04

1014: Lily mitosis 04

A light microscope image of a cell from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

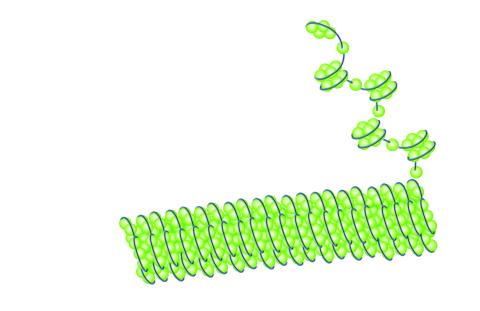

2560: Histones in chromatin

2560: Histones in chromatin

Histone proteins loop together with double-stranded DNA to form a structure that resembles beads on a string. See image 2561 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2554: RNA strand

2554: RNA strand

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) has a sugar-phosphate backbone and the bases adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and uracil (U). See image 2555 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

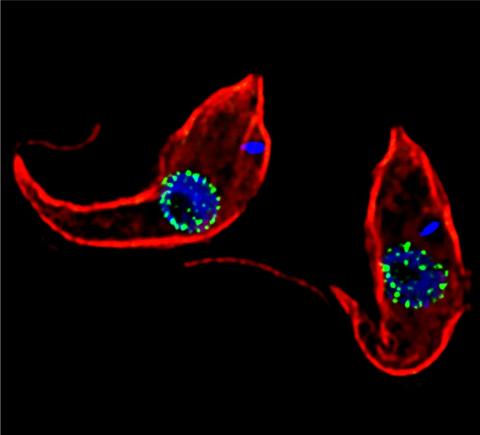

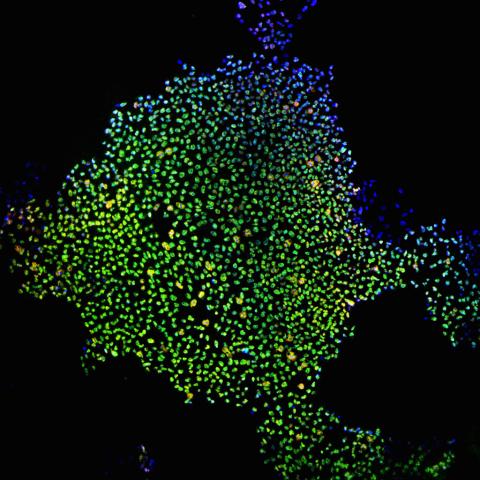

3765: Trypanosoma brucei, the cause of sleeping sickness

3765: Trypanosoma brucei, the cause of sleeping sickness

Trypanosoma brucei is a single-cell parasite that causes sleeping sickness in humans. Scientists have been studying trypanosomes for some time because of their negative effects on human and also animal health, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, because these organisms evolved on a separate path from those of animals and plants more than a billion years ago, researchers study trypanosomes to find out what traits they may harbor that are common to or different from those of other eukaryotes (i.e., those organisms having a nucleus and mitochondria). This image shows the T. brucei cell membrane in red, the DNA in the nucleus and kinetoplast (a structure unique to protozoans, including trypanosomes, which contains mitochondrial DNA) in blue and nuclear pore complexes (which allow molecules to pass into or out of the nucleus) in green. Scientists have found that the trypanosome nuclear pore complex has a unique mechanism by which it attaches to the nuclear envelope. In addition, the trypanosome nuclear pore complex differs from those of other eukaryotes because its components have a near-complete symmetry, and it lacks almost all of the proteins that in other eukaryotes studied so far are required to assemble the pore.

Michael Rout, Rockefeller University

View Media

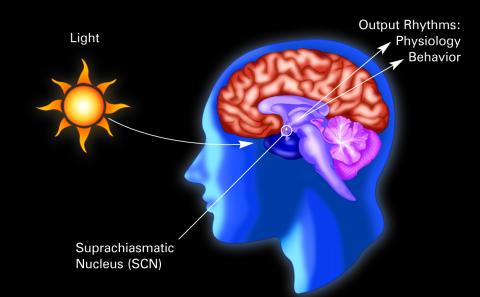

2569: Circadian rhythm (with labels)

2569: Circadian rhythm (with labels)

The human body keeps time with a master clock called the suprachiasmatic nucleus or SCN. Situated inside the brain, it's a tiny sliver of tissue about the size of a grain of rice, located behind the eyes. It sits quite close to the optic nerve, which controls vision, and this means that the SCN "clock" can keep track of day and night. The SCN helps control sleep and maintains our circadian rhythm--the regular, 24-hour (or so) cycle of ups and downs in our bodily processes such as hormone levels, blood pressure, and sleepiness. The SCN regulates our circadian rhythm by coordinating the actions of billions of miniature "clocks" throughout the body. These aren't actually clocks, but rather are ensembles of genes inside clusters of cells that switch on and off in a regular, 24-hour (or so) cycle in our physiological day.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2329: Planting roots

2329: Planting roots

At the root tips of the mustard plant Arabidopsis thaliana (red), two proteins work together to control the uptake of water and nutrients. When the cell division-promoting protein called Short-root moves from the center of the tip outward, it triggers the production of another protein (green) that confines Short-root to the nutrient-filtering endodermis. The mechanism sheds light on how genes and proteins interact in a model organism and also could inform the engineering of plants.

Philip Benfey, Duke University

View Media

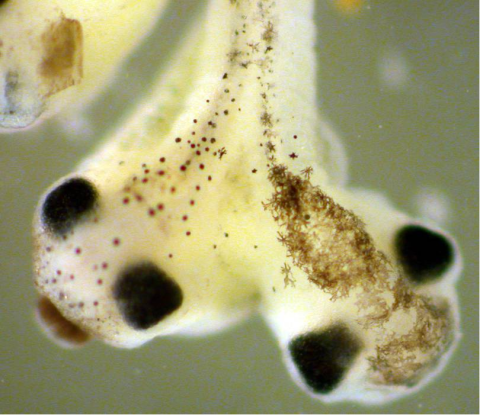

2755: Two-headed Xenopus laevis tadpole

2755: Two-headed Xenopus laevis tadpole

Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog, has long been used as a research organism for studying embryonic development. The abnormal presence of RNA encoding the signaling molecule plakoglobin causes atypical signaling, giving rise to a two-headed tadpole.

Michael Klymkowsky, University of Colorado, Boulder

View Media

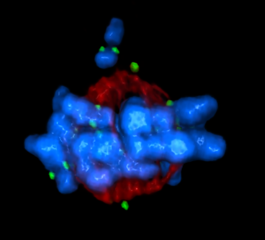

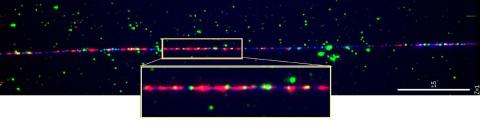

3484: Telomeres on outer edge of nucleus during cell division

3484: Telomeres on outer edge of nucleus during cell division

New research shows telomeres moving to the outer edge of the nucleus after cell division, suggesting these caps that protect chromosomes also may play a role in organizing DNA.

Laure Crabbe, Jamie Kasuboski and James Fitzpatrick, Salk Institute for Biological Studies

View Media

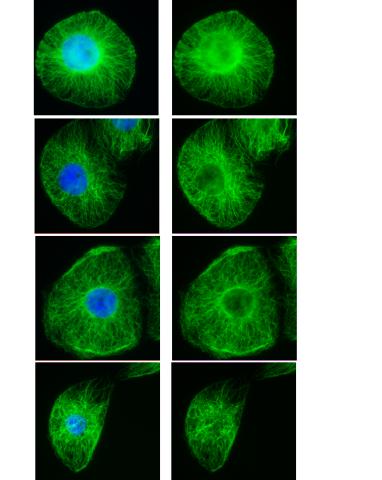

3443: Interphase in Xenopus frog cells

3443: Interphase in Xenopus frog cells

These images show frog cells in interphase. The cells are Xenopus XL177 cells, which are derived from tadpole epithelial cells. The microtubules are green and the chromosomes are blue. Related to 3442.

Claire Walczak, who took them while working as a postdoc in the laboratory of Timothy Mitchison.

View Media

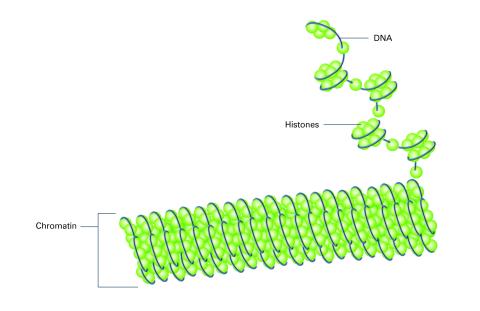

2561: Histones in chromatin (with labels)

2561: Histones in chromatin (with labels)

Histone proteins loop together with double-stranded DNA to form a structure that resembles beads on a string. See image 2560 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

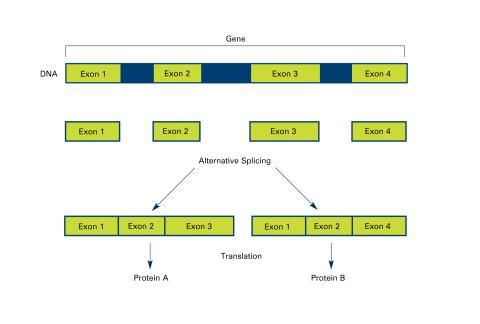

2552: Alternative splicing

2552: Alternative splicing

Arranging exons in different patterns, called alternative splicing, enables cells to make different proteins from a single gene. See image 2553 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

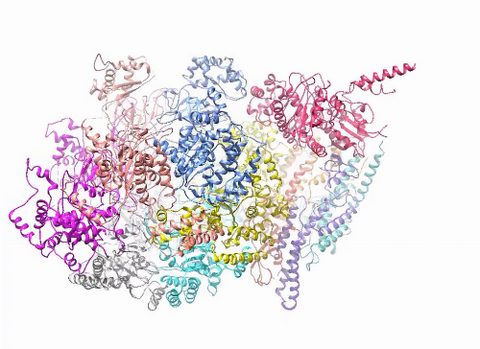

3750: A dynamic model of the DNA helicase protein complex

3750: A dynamic model of the DNA helicase protein complex

This short video shows a model of the DNA helicase in yeast. This DNA helicase has 11 proteins that work together to unwind DNA during the process of copying it, called DNA replication. Scientists used a technique called cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which allowed them to study the helicase structure in solution rather than in static crystals. Cryo-EM in combination with computer modeling therefore allows researchers to see movements and other dynamic changes in the protein. The cryo-EM approach revealed the helicase structure at much greater resolution than could be obtained before. The researchers think that a repeated motion within the protein as shown in the video helps it move along the DNA strand. To read more about DNA helicase and this proposed mechanism, see this news release by Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Huilin Li, Stony Brook University

View Media

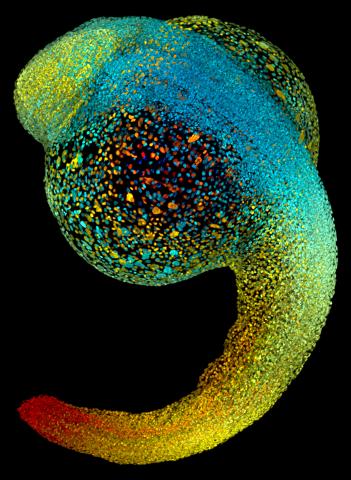

3644: Zebrafish embryo

3644: Zebrafish embryo

Just 22 hours after fertilization, this zebrafish embryo is already taking shape. By 36 hours, all of the major organs will have started to form. The zebrafish's rapid growth and see-through embryo make it ideal for scientists studying how organs develop.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Philipp Keller, Bill Lemon, Yinan Wan, and Kristin Branson, Janelia Farm Research Campus, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Ashburn, Va.

View Media

1011: Lily mitosis 11

1011: Lily mitosis 11

A light microscope image of cells from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue. Here, condensed chromosomes are clearly visible and have separated into the opposite sides of a dividing cell.

Related to images 1010, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

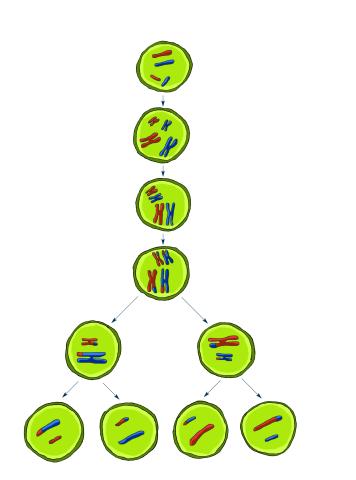

2545: Meiosis illustration

2545: Meiosis illustration

Meiosis is the process whereby a cell reduces its chromosomes from diploid to haploid in creating eggs or sperm. See image 2546 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2565: Recombinant DNA (with labels)

2565: Recombinant DNA (with labels)

To splice a human gene (in this case, the one for insulin) into a plasmid, scientists take the plasmid out of an E. coli bacterium, cut the plasmid with a restriction enzyme, and splice in insulin-making human DNA. The resulting hybrid plasmid can be inserted into another E. coli bacterium, where it multiplies along with the bacterium. There, it can produce large quantities of insulin. See image 2564 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

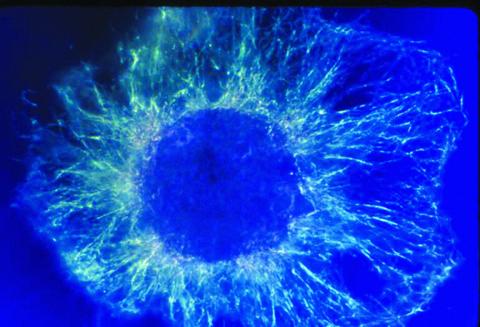

2429: Highlighted cells

2429: Highlighted cells

The cytoskeleton (green) and DNA (purple) are highlighed in these cells by immunofluorescence.

Torsten Wittmann, Scripps Research Institute

View Media

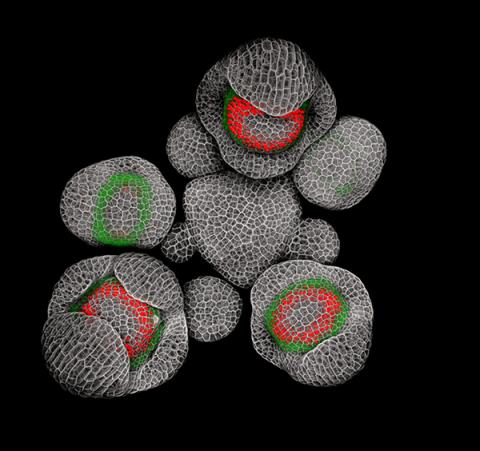

3743: Developing Arabidopsis flower buds

3743: Developing Arabidopsis flower buds

Flower development is a carefully orchestrated, genetically programmed process that ensures that the male (stamen) and female (pistil) organs form in the right place and at the right time in the flower. In this image of young Arabidopsis flower buds, the gene SUPERMAN (red) is activated at the boundary between the cells destined to form the male and female parts. SUPERMAN activity prevents the central cells, which will ultimately become the female pistil, from activating the gene APETALA3 (green), which induces formation of male flower organs. The goal of this research is to find out how plants maintain cells (called stem cells) that have the potential to develop into any type of cell and how genetic and environmental factors cause stem cells to develop and specialize into different cell types. This work informs future studies in agriculture, medicine and other fields.

Nathanaël Prunet, Caltech

View Media

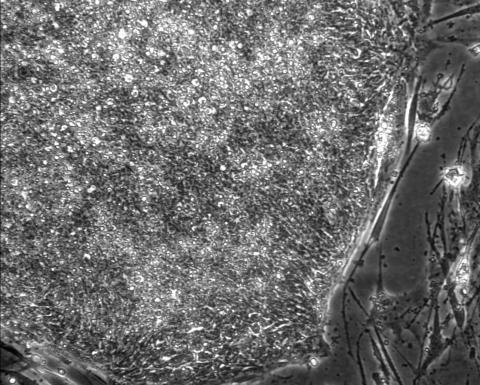

2603: Induced stem cells from adult skin 01

2603: Induced stem cells from adult skin 01

These cells are induced stem cells made from human adult skin cells that were genetically reprogrammed to mimic embryonic stem cells. The induced stem cells were made potentially safer by removing the introduced genes and the viral vector used to ferry genes into the cells, a loop of DNA called a plasmid. The work was accomplished by geneticist Junying Yu in the laboratory of James Thomson, a University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health professor and the director of regenerative biology for the Morgridge Institute for Research.

James Thomson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

1018: Lily mitosis 12

1018: Lily mitosis 12

A light microscope image of a cell from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue. Here, condensed chromosomes are clearly visible near the end of a round of mitosis.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1019, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1019, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

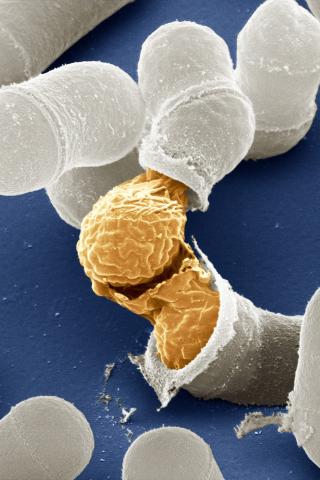

3614: Birth of a yeast cell

3614: Birth of a yeast cell

Yeast make bread, beer, and wine. And like us, yeast can reproduce sexually. A mother and father cell fuse and create one large cell that contains four offspring. When environmental conditions are favorable, the offspring are released, as shown here. Yeast are also a popular study subject for scientists. Research on yeast has yielded vast knowledge about basic cellular and molecular biology as well as about myriad human diseases, including colon cancer and various metabolic disorders.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Juergen Berger, Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, and Maria Langegger, Friedrich Miescher Laboratory of the Max Planck Society, Germany

View Media

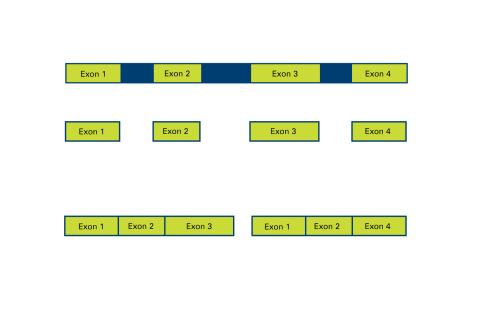

2553: Alternative splicing (with labels)

2553: Alternative splicing (with labels)

Arranging exons in different patterns, called alternative splicing, enables cells to make different proteins from a single gene. Featured in The New Genetics.

See image 2552 for an unlabeled version of this illustration.

See image 2552 for an unlabeled version of this illustration.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

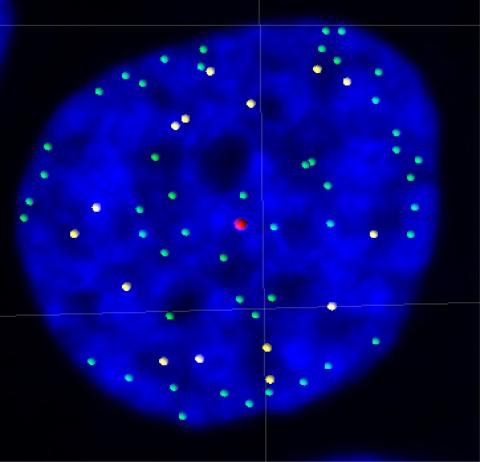

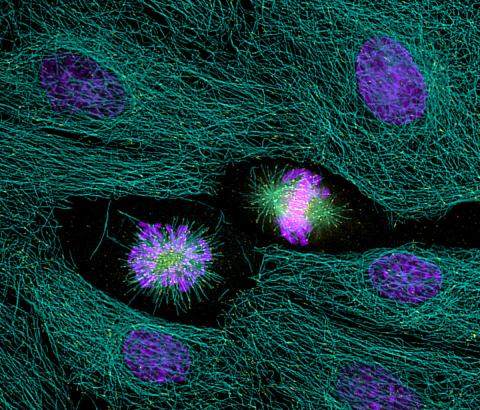

5765: Mitotic cell awaits chromosome alignment

5765: Mitotic cell awaits chromosome alignment

During mitosis, spindle microtubules (red) attach to chromosome pairs (blue), directing them to the spindle equator. This midline alignment is critical for equal distribution of chromosomes in the dividing cell. Scientists are interested in how the protein kinase Plk1 (green) regulates this activity in human cells. Image is a volume projection of multiple deconvolved z-planes acquired with a Nikon widefield fluorescence microscope. This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call. Related to image 5766.

The research that led to this image was funded by NIGMS.

View Media

The research that led to this image was funded by NIGMS.

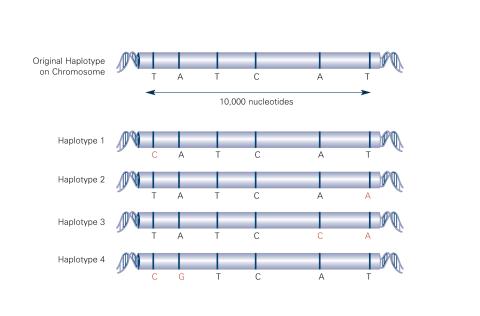

2567: Haplotypes (with labels)

2567: Haplotypes (with labels)

Haplotypes are combinations of gene variants that are likely to be inherited together within the same chromosomal region. In this example, an original haplotype (top) evolved over time to create three newer haplotypes that each differ by a few nucleotides (red). See image 2566 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

1058: Lily mitosis 01

1058: Lily mitosis 01

A light microscope image shows the chromosomes, stained dark blue, in a dividing cell of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

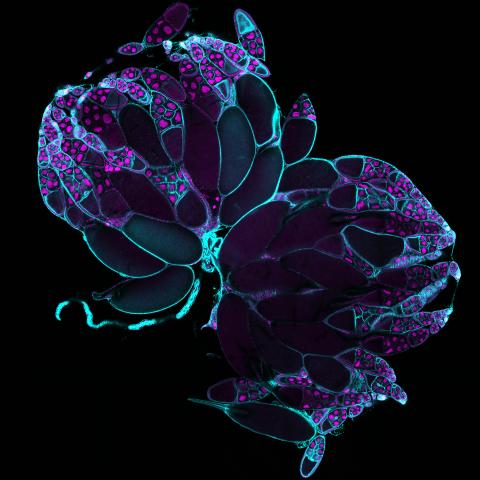

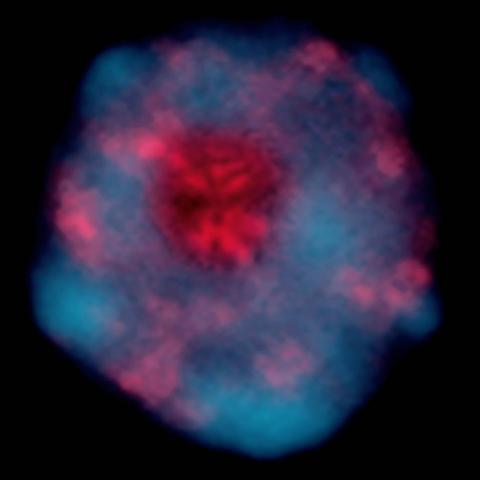

6807: Fruit fly ovaries

6807: Fruit fly ovaries

Fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) ovaries with DNA shown in magenta and actin filaments shown in light blue. This image was captured using a confocal laser scanning microscope.

Related to image 6806.

Related to image 6806.

Vladimir I. Gelfand, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University.

View Media

6773: Endoplasmic reticulum abnormalities

6773: Endoplasmic reticulum abnormalities

Human cells with the gene that codes for the protein FIT2 deleted. Green indicates an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resident protein. The lack of FIT2 affected the structure of the ER and caused the resident protein to cluster in ER membrane aggregates, seen as large, bright-green spots. Red shows where the degradation of cell parts—called autophagy—is taking place, and the nucleus is visible in blue. This image was captured using a confocal microscope.

Michel Becuwe, Harvard University.

View Media

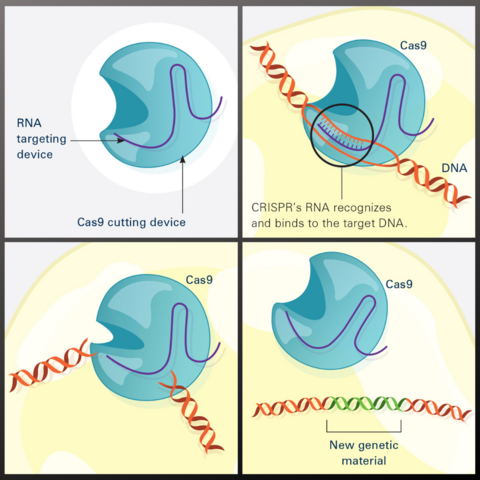

5815: Introduction to Genome Editing Using CRISPR/Cas9

5815: Introduction to Genome Editing Using CRISPR/Cas9

Genome editing using CRISPR/Cas9 is a rapidly expanding field of scientific research with emerging applications in disease treatment, medical therapeutics and bioenergy, just to name a few. This technology is now being used in laboratories all over the world to enhance our understanding of how living biological systems work, how to improve treatments for genetic diseases and how to develop energy solutions for a better future.

Janet Iwasa

View Media

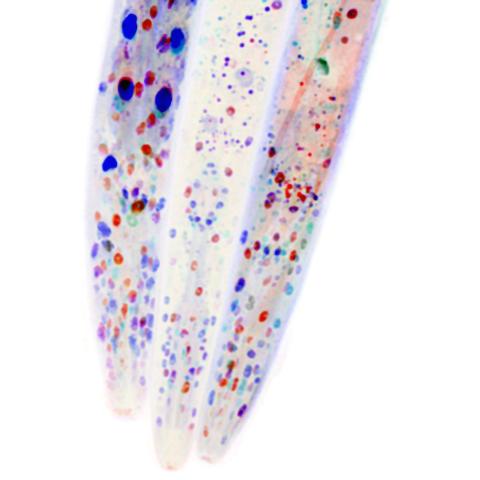

6534: Mosaicism in C. elegans (White Background)

6534: Mosaicism in C. elegans (White Background)

In the worm C. elegans, double-stranded RNA made in neurons can silence matching genes in a variety of cell types through the transport of RNA between cells. The head region of three worms that were genetically modified to express a fluorescent protein were imaged and the images were color-coded based on depth. The worm on the left lacks neuronal double-stranded RNA and thus every cell is fluorescent. In the middle worm, the expression of the fluorescent protein is silenced by neuronal double-stranded RNA and thus most cells are not fluorescent. The worm on the right lacks an enzyme that amplifies RNA for silencing. Surprisingly, the identities of the cells that depend on this enzyme for gene silencing are unpredictable. As a result, worms of identical genotype are nevertheless random mosaics for how the function of gene silencing is carried out. For more, see journal article and press release. Related to image 6532.

Snusha Ravikumar, Ph.D., University of Maryland, College Park, and Antony M. Jose, Ph.D., University of Maryland, College Park

View Media

2588: Genetic patchworks

2588: Genetic patchworks

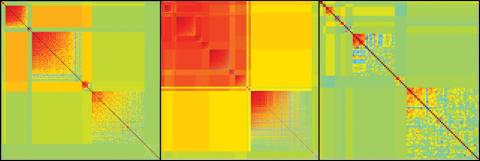

Each point in these colorful patchworks represents the correlation between two sleep-associated genes in fruit flies. Vibrant reds and oranges represent high and intermediate degrees of association between the genes, respectively. Genes in these areas show similar activity patterns in different fly lines. Cool blues represent gene pairs where one partner's activity is high and the other's is low. The green areas show pairs with activities that are not correlated. These quilt-like depictions help illustrate a recent finding that genes act in teams to influence sleep patterns.

Susan Harbison and Trudy Mackay, North Carolina State University

View Media

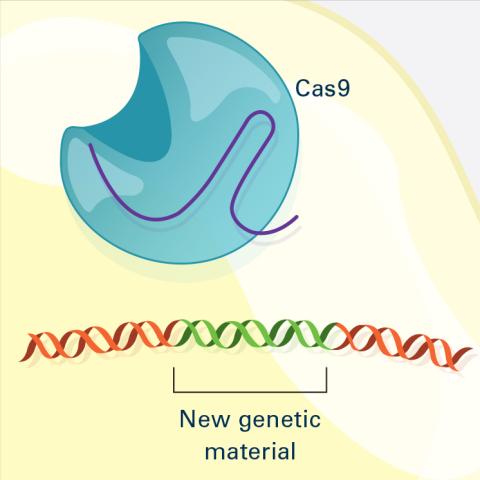

6488: CRISPR Illustration Frame 4

6488: CRISPR Illustration Frame 4

This illustration shows, in simplified terms, how the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used as a gene-editing tool. The CRISPR system has two components joined together: a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence) and a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA). This frame (4 out of 4) shows a repaired DNA strand with new genetic material that researchers can introduce, which the cell automatically incorporates into the gap when it repairs the broken DNA.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and find the full CRIPSR illustration here.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and find the full CRIPSR illustration here.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

View Media

1019: Lily mitosis 13

1019: Lily mitosis 13

A light microscope image of cells from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue. Here, two cells have formed after a round of mitosis.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

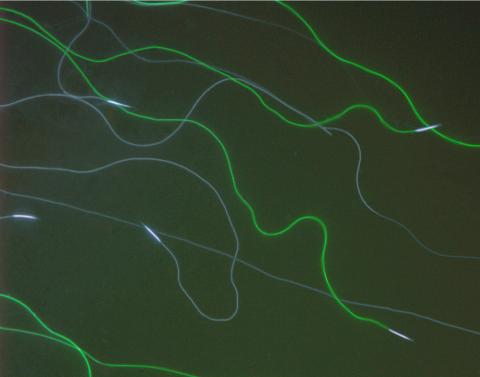

2683: GFP sperm

2683: GFP sperm

Fruit fly sperm cells glow bright green when they express the gene for green fluorescent protein (GFP).

View Media

3597: DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC)

3597: DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC)

A study published in March 2012 used cryo-electron microscopy to determine the structure of the DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC), a semi-circular, protein complex (yellow) that recognizes and binds DNA to start the replication process. The ORC appears to wrap around and bend approximately 70 base pairs of double stranded DNA (red and blue). Also shown is the protein Cdc6 (green), which is also involved in the initiation of DNA replication. Related to video 3307 that shows the structure from different angles. From a Brookhaven National Laboratory news release, "Study Reveals How Protein Machinery Binds and Wraps DNA to Start Replication."

Huilin Li, Brookhaven National Laboratory

View Media

2475: Chromosome fiber 01

2475: Chromosome fiber 01

This microscopic image shows a chromatin fiber--a DNA molecule bound to naturally occurring proteins.

Marc Green and Susan Forsburg, University of Southern California

View Media

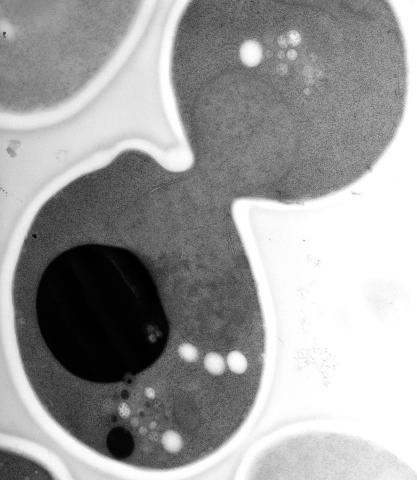

5770: EM of yeast cell division

5770: EM of yeast cell division

Cell division is an incredibly coordinated process. It not only ensures that the new cells formed during this event have a full set of chromosomes, but also that they are endowed with all the cellular materials, including proteins, lipids and small functional compartments called organelles, that are required for normal cell activity. This proper apportioning of essential cell ingredients helps each cell get off to a running start.

This image shows an electron microscopy (EM) thin section taken at 10,000x magnification of a dividing yeast cell over-expressing the protein ubiquitin, which is involved in protein degradation and recycling. The picture features mother and daughter endosome accumulations (small organelles with internal vesicles), a darkly stained vacuole and a dividing nucleus in close contact with a cadre of lipid droplets (unstained spherical bodies). Other dynamic events are also visible, such as spindle microtubules in the nucleus and endocytic pits at the plasma membrane.

These extensive details were revealed thanks to a preservation method involving high-pressure freezing, freeze-substitution and Lowicryl HM20 embedding.

This image shows an electron microscopy (EM) thin section taken at 10,000x magnification of a dividing yeast cell over-expressing the protein ubiquitin, which is involved in protein degradation and recycling. The picture features mother and daughter endosome accumulations (small organelles with internal vesicles), a darkly stained vacuole and a dividing nucleus in close contact with a cadre of lipid droplets (unstained spherical bodies). Other dynamic events are also visible, such as spindle microtubules in the nucleus and endocytic pits at the plasma membrane.

These extensive details were revealed thanks to a preservation method involving high-pressure freezing, freeze-substitution and Lowicryl HM20 embedding.

Matthew West and Greg Odorizzi, University of Colorado

View Media

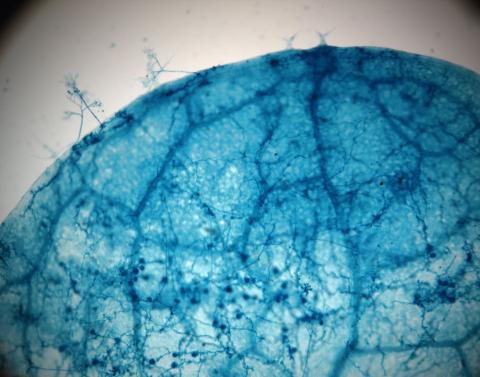

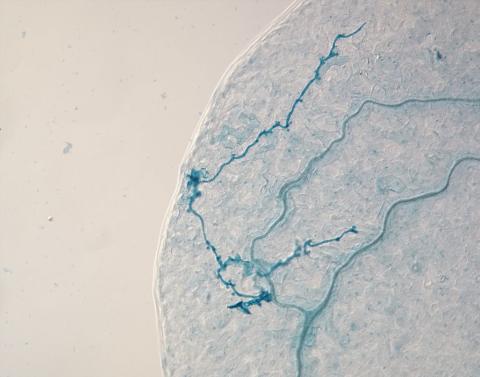

2782: Disease-susceptible Arabidopsis leaf

2782: Disease-susceptible Arabidopsis leaf

This is a magnified view of an Arabidopsis thaliana leaf after several days of infection with the pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. The pathogen's blue hyphae grow throughout the leaf. On the leaf's edges, stalk-like structures called sporangiophores are beginning to mature and will release the pathogen's spores. Inside the leaf, the large, deep blue spots are structures called oopsorangia, also full of spores. Compare this response to that shown in Image 2781. Jeff Dangl has been funded by NIGMS to study the interactions between pathogens and hosts that allow or suppress infection.

Jeff Dangl, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

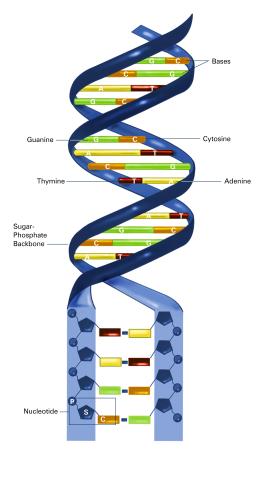

2542: Nucleotides make up DNA (with labels)

2542: Nucleotides make up DNA (with labels)

DNA consists of two long, twisted chains made up of nucleotides. Each nucleotide contains one base, one phosphate molecule, and the sugar molecule deoxyribose. The bases in DNA nucleotides are adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. See image 2541 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2604: Induced stem cells from adult skin 02

2604: Induced stem cells from adult skin 02

These cells are induced stem cells made from human adult skin cells that were genetically reprogrammed to mimic embryonic stem cells. The induced stem cells were made potentially safer by removing the introduced genes and the viral vector used to ferry genes into the cells, a loop of DNA called a plasmid. The work was accomplished by geneticist Junying Yu in the laboratory of James Thomson, a University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health professor and the director of regenerative biology for the Morgridge Institute for Research.

James Thomson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

2780: Arabidopsis leaf injected with a pathogen

2780: Arabidopsis leaf injected with a pathogen

This is a magnified view of an Arabidopsis thaliana leaf eight days after being infected with the pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis, which is closely related to crop pathogens that cause 'downy mildew' diseases. It is also more distantly related to the agent that caused the Irish potato famine. The veins of the leaf are light blue; in darker blue are the pathogen's hyphae growing through the leaf. The small round blobs along the length of the hyphae are called haustoria; each is invading a single plant cell to suck nutrients from the cell. Jeff Dangl and other NIGMS-supported researchers investigate how this pathogen and other like it use virulence mechanisms to suppress host defense and help the pathogens grow.

Jeff Dangl, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

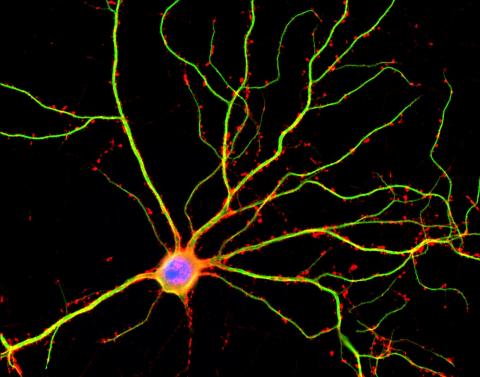

3687: Hippocampal neuron in culture

3687: Hippocampal neuron in culture

Hippocampal neuron in culture. Dendrites are green, dendritic spines are red and DNA in cell's nucleus is blue. Image is featured on Biomedical Beat blog post Anesthesia and Brain Cells: A Temporary Disruption?

Shelley Halpain, UC San Diego

View Media

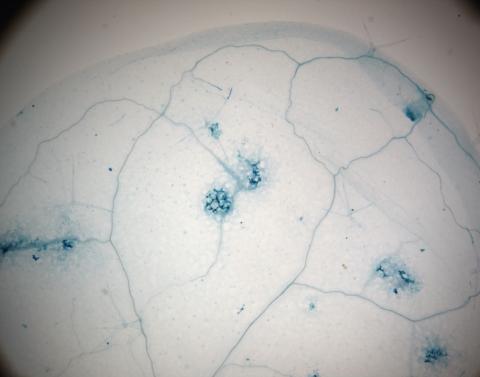

2781: Disease-resistant Arabidopsis leaf

2781: Disease-resistant Arabidopsis leaf

This is a magnified view of an Arabidopsis thaliana leaf a few days after being exposed to the pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. The plant from which this leaf was taken is genetically resistant to the pathogen. The spots in blue show areas of localized cell death where infection occurred, but it did not spread. Compare this response to that shown in Image 2782. Jeff Dangl has been funded by NIGMS to study the interactions between pathogens and hosts that allow or suppress infection.

Jeff Dangl, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

7036: CRISPR Illustration

7036: CRISPR Illustration

This illustration shows, in simplified terms, how the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used as a gene-editing tool.

Frame 1 shows the two components of the CRISPR system: a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA), and a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence).

In frame 2, the CRISPR machine locates the target DNA sequence once inserted into a cell.

In frame 3, the Cas9 enzyme cuts both strands of the DNA.

Frame 4 shows a repaired DNA strand with new genetic material that researchers can introduce, which the cell automatically incorporates into the gap when it repairs the broken DNA.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video.

Download the individual frames: Frame 1, Frame 2, Frame 3, and Frame 4.

Frame 1 shows the two components of the CRISPR system: a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA), and a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence).

In frame 2, the CRISPR machine locates the target DNA sequence once inserted into a cell.

In frame 3, the Cas9 enzyme cuts both strands of the DNA.

Frame 4 shows a repaired DNA strand with new genetic material that researchers can introduce, which the cell automatically incorporates into the gap when it repairs the broken DNA.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video.

Download the individual frames: Frame 1, Frame 2, Frame 3, and Frame 4.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

View Media

2318: Gene silencing

2318: Gene silencing

Pretty in pink, the enzyme histone deacetylase (HDA6) stands out against a background of blue-tinted DNA in the nucleus of an Arabidopsis plant cell. Here, HDA6 concentrates in the nucleolus (top center), where ribosomal RNA genes reside. The enzyme silences the ribosomal RNA genes from one parent while those from the other parent remain active. This chromosome-specific silencing of ribosomal RNA genes is an unusual phenomenon observed in hybrid plants.

Olga Pontes and Craig Pikaard, Washington University

View Media

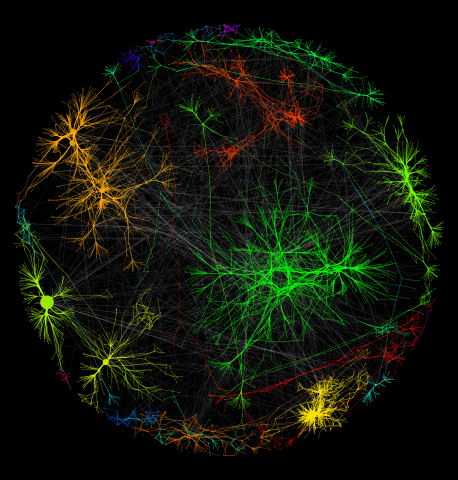

3730: A molecular interaction network in yeast 1

3730: A molecular interaction network in yeast 1

The image visualizes a part of the yeast molecular interaction network. The lines in the network represent connections among genes (shown as little dots) and different-colored networks indicate subnetworks, for instance, those in specific locations or pathways in the cell. Researchers use gene or protein expression data to build these networks; the network shown here was visualized with a program called Cytoscape. By following changes in the architectures of these networks in response to altered environmental conditions, scientists can home in on those genes that become central "hubs" (highly connected genes), for example, when a cell encounters stress. They can then further investigate the precise role of these genes to uncover how a cell's molecular machinery deals with stress or other factors. Related to images 3732 and 3733.

Keiichiro Ono, UCSD

View Media

5764: Host infection stimulates antibiotic resistance

5764: Host infection stimulates antibiotic resistance

This illustration shows pathogenic bacteria behave like a Trojan horse: switching from antibiotic susceptibility to resistance during infection. Salmonella are vulnerable to antibiotics while circulating in the blood (depicted by fire on red blood cell) but are highly resistant when residing within host macrophages. This leads to treatment failure with the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria.

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call, and the research was funded in part by NIGMS.

View Media

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call, and the research was funded in part by NIGMS.

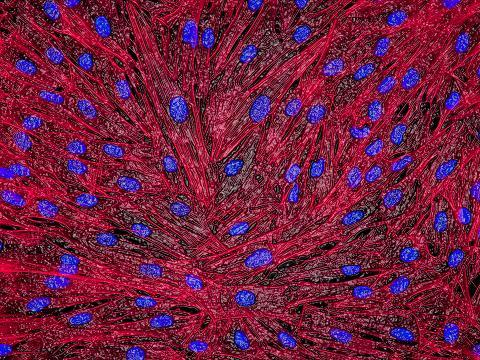

3670: DNA and actin in cultured fibroblast cells

3670: DNA and actin in cultured fibroblast cells

DNA (blue) and actin (red) in cultured fibroblast cells.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

6999: HIV enzyme

6999: HIV enzyme

These images model the molecular structures of three enzymes with critical roles in the life cycle of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). At the top, reverse transcriptase (orange) creates a DNA copy (yellow) of the virus's RNA genome (blue). In the middle image, integrase (magenta) inserts this DNA copy in the DNA genome (green) of the infected cell. At the bottom, much later in the viral life cycle, protease (turquoise) chops up a chain of HIV structural protein (purple) to generate the building blocks for making new viruses. See these enzymes in action on PDB 101’s video A Molecular View of HIV Therapy.

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

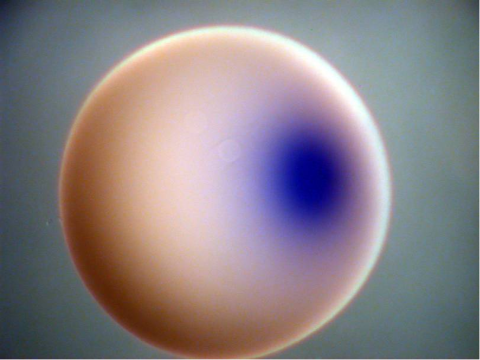

2753: Xenopus laevis egg

2753: Xenopus laevis egg

Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog, has long been used as a model organism for studying embryonic development. In this image, RNA encoding the transcription factor Sox 7 (dark blue) is shown to predominate at the vegetal pole, the yolk-rich portion, of a Xenopus laevis frog egg. Sox 7 protein is important to the regulation of embryonic development.

Michael Klymkowsky, University of Colorado, Boulder

View Media