Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

2764: Painted chromosomes

2764: Painted chromosomes

Like a paint-by-numbers picture, painted probes tint individual human chromosomes by targeting specific DNA sequences. Chromosome 13 is colored green, chromosome 14 is in red and chromosome 15 is painted yellow. The image shows two examples of fused chromosomes—a pair of chromosomes 15 connected head-to-head (yellow dumbbell-shaped structure) and linked chromosomes 13 and 14 (green and red dumbbell). These fused chromosomes—called dicentric chromosomes—may cause fertility problems or other difficulties in people.

Beth A. Sullivan, Duke University

View Media

3724: Snowflake DNA origami

3724: Snowflake DNA origami

An atomic force microscopy image shows DNA folded into an intricate, computer-designed structure. The image is featured on Biomedical Beat blog post Cool Images: A Holiday-Themed Collection. For more background on DNA origami, see Cool Image: DNA Origami. See also related image 3690.

Hao Yan, Arizona State University

View Media

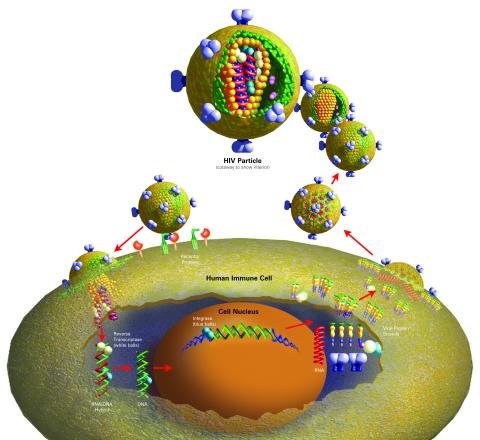

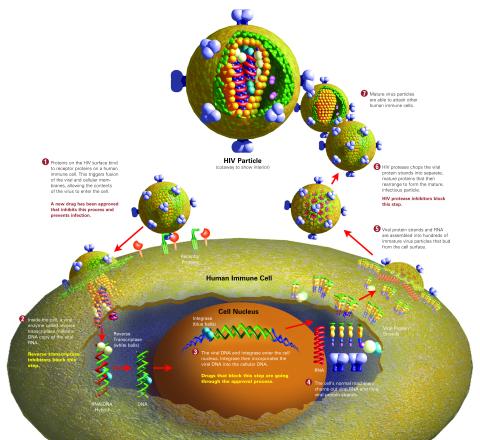

2514: Life of an AIDS virus (with labels)

2514: Life of an AIDS virus (with labels)

HIV is a retrovirus, a type of virus that carries its genetic material not as DNA but as RNA. Long before anyone had heard of HIV, researchers in labs all over the world studied retroviruses, tracing out their life cycle and identifying the key proteins the viruses use to infect cells. When HIV was identified as a retrovirus, these studies gave AIDS researchers an immediate jump-start. The previously identified viral proteins became initial drug targets. See images 2513 and 2515 for other versions of this illustration. Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

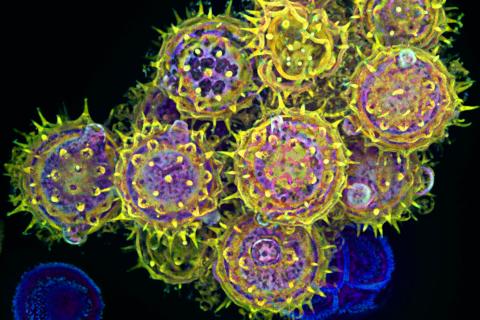

3609: Pollen grains: male germ cells in plants and a cause of seasonal allergies

3609: Pollen grains: male germ cells in plants and a cause of seasonal allergies

Those of us who get sneezy and itchy-eyed every spring or fall may have pollen grains, like those shown here, to blame. Pollen grains are the male germ cells of plants, released to fertilize the corresponding female plant parts. When they are instead inhaled into human nasal passages, they can trigger allergies.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Edna, Gil, and Amit Cukierman, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, Pa.

View Media

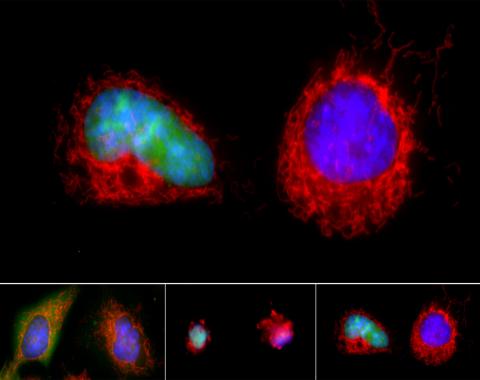

3486: Apoptosis reversed

3486: Apoptosis reversed

Two healthy cells (bottom, left) enter into apoptosis (bottom, center) but spring back to life after a fatal toxin is removed (bottom, right; top).

Hogan Tang of the Denise Montell Lab, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

View Media

3750: A dynamic model of the DNA helicase protein complex

3750: A dynamic model of the DNA helicase protein complex

This short video shows a model of the DNA helicase in yeast. This DNA helicase has 11 proteins that work together to unwind DNA during the process of copying it, called DNA replication. Scientists used a technique called cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which allowed them to study the helicase structure in solution rather than in static crystals. Cryo-EM in combination with computer modeling therefore allows researchers to see movements and other dynamic changes in the protein. The cryo-EM approach revealed the helicase structure at much greater resolution than could be obtained before. The researchers think that a repeated motion within the protein as shown in the video helps it move along the DNA strand. To read more about DNA helicase and this proposed mechanism, see this news release by Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Huilin Li, Stony Brook University

View Media

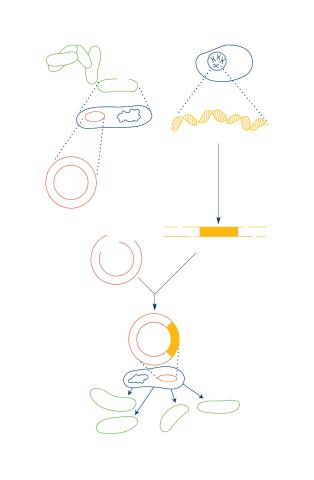

2564: Recombinant DNA

2564: Recombinant DNA

To splice a human gene into a plasmid, scientists take the plasmid out of an E. coli bacterium, cut the plasmid with a restriction enzyme, and splice in human DNA. The resulting hybrid plasmid can be inserted into another E. coli bacterium, where it multiplies along with the bacterium. There, it can produce large quantities of human protein. See image 2565 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

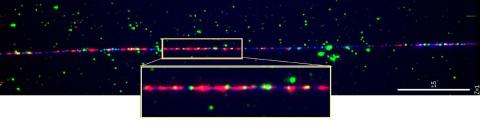

2475: Chromosome fiber 01

2475: Chromosome fiber 01

This microscopic image shows a chromatin fiber--a DNA molecule bound to naturally occurring proteins.

Marc Green and Susan Forsburg, University of Southern California

View Media

3719: CRISPR illustration

3719: CRISPR illustration

This illustration shows, in simplified terms, how the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used as a gene-editing tool.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and download the four images of the CRIPSR illustration here.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and download the four images of the CRIPSR illustration here.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

View Media

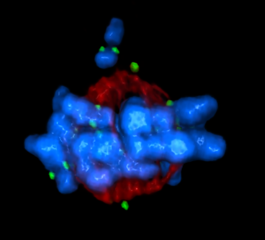

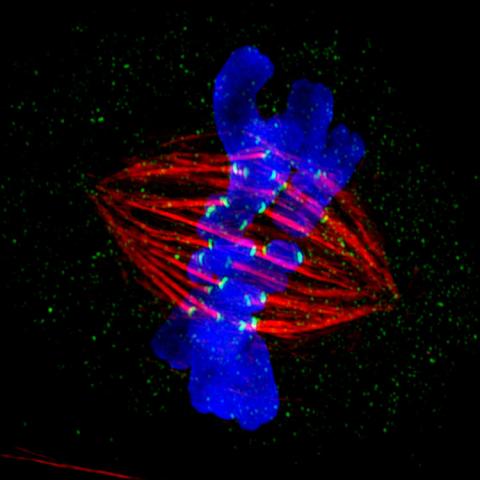

5765: Mitotic cell awaits chromosome alignment

5765: Mitotic cell awaits chromosome alignment

During mitosis, spindle microtubules (red) attach to chromosome pairs (blue), directing them to the spindle equator. This midline alignment is critical for equal distribution of chromosomes in the dividing cell. Scientists are interested in how the protein kinase Plk1 (green) regulates this activity in human cells. Image is a volume projection of multiple deconvolved z-planes acquired with a Nikon widefield fluorescence microscope. This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call. Related to image 5766.

The research that led to this image was funded by NIGMS.

View Media

The research that led to this image was funded by NIGMS.

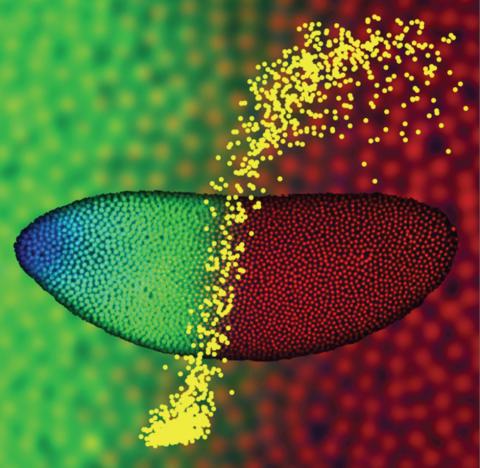

2733: Early development in Arabidopsis

2733: Early development in Arabidopsis

Early on, this Arabidopsis plant embryo picks sides: While one end will form the shoot, the other will take root underground. Short pieces of RNA in the bottom half (blue) make sure that shoot-forming genes are expressed only in the embryo's top half (green), eventually allowing a seedling to emerge with stems and leaves. Like animals, plants follow a carefully orchestrated polarization plan and errors can lead to major developmental defects, such as shoots above and below ground. Because the complex gene networks that coordinate this development in plants and animals share important similarities, studying polarity in Arabidopsis--a model organism--could also help us better understand human development.

Zachery R. Smith, Jeff Long lab at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies

View Media

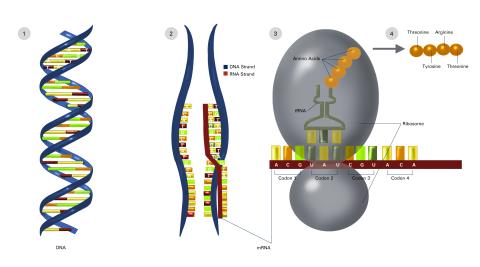

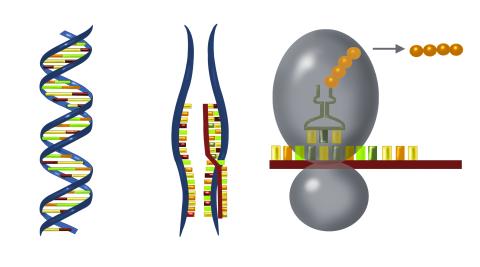

2549: Central dogma, illustrated (with labels and numbers for stages)

2549: Central dogma, illustrated (with labels and numbers for stages)

DNA encodes RNA, which encodes protein. DNA is transcribed to make messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA sequence (dark red strand) is complementary to the DNA sequence (blue strand). On ribosomes, transfer RNA (tRNA) reads three nucleotides at a time in mRNA to bring together the amino acids that link up to make a protein. See image 2548 for a version of this illustration that isn't numbered and 2547 for a an entirely unlabeled version. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2547: Central dogma, illustrated

2547: Central dogma, illustrated

DNA encodes RNA, which encodes protein. DNA is transcribed to make messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA sequence (dark red strand) is complementary to the DNA sequence (blue strand). On ribosomes, transfer RNA (tRNA) reads three nucleotides at a time in mRNA to bring together the amino acids that link up to make a protein. See image 2548 for a labeled version of this illustration and 2549 for a labeled and numbered version. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

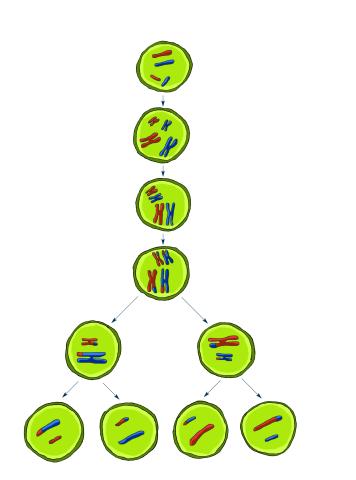

2545: Meiosis illustration

2545: Meiosis illustration

Meiosis is the process whereby a cell reduces its chromosomes from diploid to haploid in creating eggs or sperm. See image 2546 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

3254: Pulsating response to stress in bacteria - video

3254: Pulsating response to stress in bacteria - video

By attaching fluorescent proteins to the genetic circuit responsible for B. subtilis's stress response, researchers can observe the cells' pulses as green flashes. This video shows flashing cells as they multiply over the course of more than 12 hours. In response to a stressful environment like one lacking food, B. subtilis activates a large set of genes that help it respond to the hardship. Instead of leaving those genes on as previously thought, researchers discovered that the bacteria flip the genes on and off, increasing the frequency of these pulses with increasing stress. See entry 3253 for a related still image.

Michael Elowitz, Caltech University

View Media

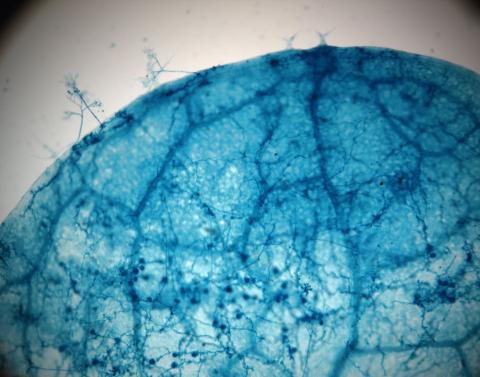

2782: Disease-susceptible Arabidopsis leaf

2782: Disease-susceptible Arabidopsis leaf

This is a magnified view of an Arabidopsis thaliana leaf after several days of infection with the pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. The pathogen's blue hyphae grow throughout the leaf. On the leaf's edges, stalk-like structures called sporangiophores are beginning to mature and will release the pathogen's spores. Inside the leaf, the large, deep blue spots are structures called oopsorangia, also full of spores. Compare this response to that shown in Image 2781. Jeff Dangl has been funded by NIGMS to study the interactions between pathogens and hosts that allow or suppress infection.

Jeff Dangl, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

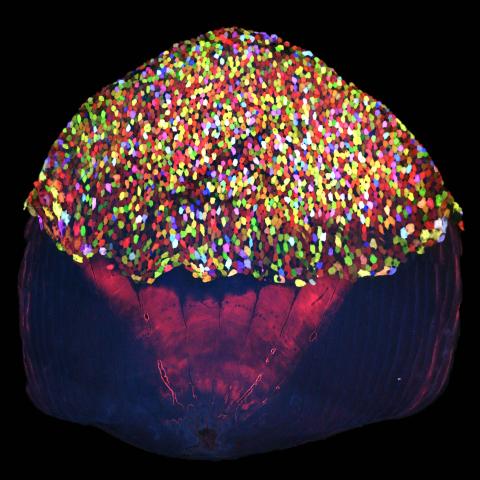

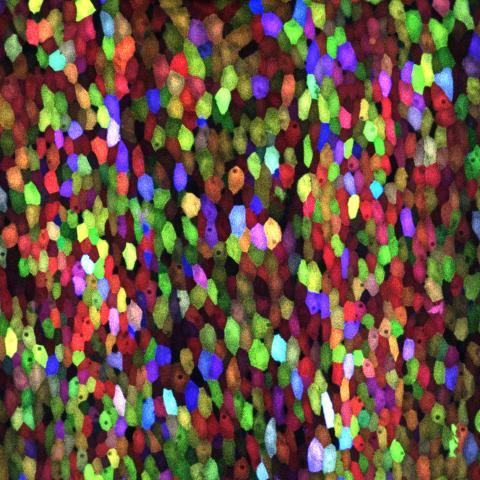

3783: A multicolored fish scale 2

3783: A multicolored fish scale 2

Each of the tiny colored specs in this image is a cell on the surface of a fish scale. To better understand how wounds heal, scientists have inserted genes that make cells brightly glow in different colors into the skin cells of zebrafish, a fish often used in laboratory research. The colors enable the researchers to track each individual cell, for example, as it moves to the location of a cut or scrape over the course of several days. These technicolor fish endowed with glowing skin cells dubbed "skinbow" provide important insight into how tissues recover and regenerate after an injury.

For more information on skinbow fish, see the Biomedical Beat blog post Visualizing Skin Regeneration in Real Time and a press release from Duke University highlighting this research. Related to image 3782.

For more information on skinbow fish, see the Biomedical Beat blog post Visualizing Skin Regeneration in Real Time and a press release from Duke University highlighting this research. Related to image 3782.

Chen-Hui Chen and Kenneth Poss, Duke University

View Media

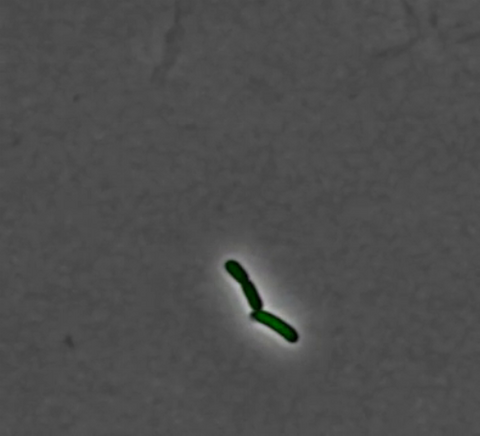

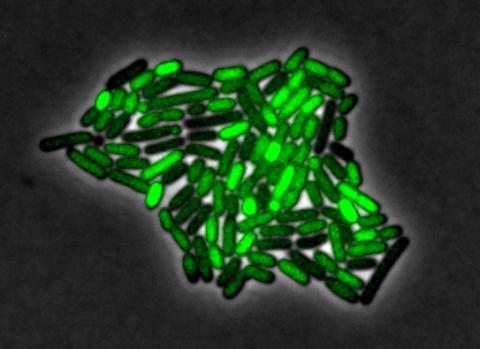

3253: Pulsating response to stress in bacteria

3253: Pulsating response to stress in bacteria

By attaching fluorescent proteins to the genetic circuit responsible for B. subtilis's stress response, researchers can observe the cells' pulses as green flashes. In response to a stressful environment like one lacking food, B. subtilis activates a large set of genes that help it respond to the hardship. Instead of leaving those genes on as previously thought, researchers discovered that the bacteria flip the genes on and off, increasing the frequency of these pulses with increasing stress. See entry 3254 for the related video.

Michael Elowitz, Caltech University

View Media

5766: A chromosome goes missing in anaphase

5766: A chromosome goes missing in anaphase

Anaphase is the critical step during mitosis when sister chromosomes are disjoined and directed to opposite spindle poles, ensuring equal distribution of the genome during cell division. In this image, one pair of sister chromosomes at the top was lost and failed to divide after chemical inhibition of polo-like kinase 1. This image depicts chromosomes (blue) separating away from the spindle mid-zone (red). Kinetochores (green) highlight impaired movement of some chromosomes away from the mid-zone or the failure of sister chromatid separation (top). Scientists are interested in detailing the signaling events that are disrupted to produce this effect. The image is a volume projection of multiple deconvolved z-planes acquired with a Nikon widefield fluorescence microscope.

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call. The research that led to this image was funded by NIGMS.

Related to image 5765.

View Media

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call. The research that led to this image was funded by NIGMS.

Related to image 5765.

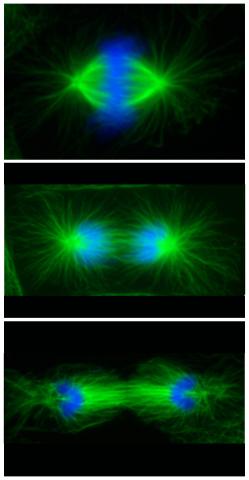

3442: Cell division phases in Xenopus frog cells

3442: Cell division phases in Xenopus frog cells

These images show three stages of cell division in Xenopus XL177 cells, which are derived from tadpole epithelial cells. They are (from top): metaphase, anaphase and telophase. The microtubules are green and the chromosomes are blue. Related to 3443.

Claire Walczak, who took them while working as a postdoc in the laboratory of Timothy Mitchison

View Media

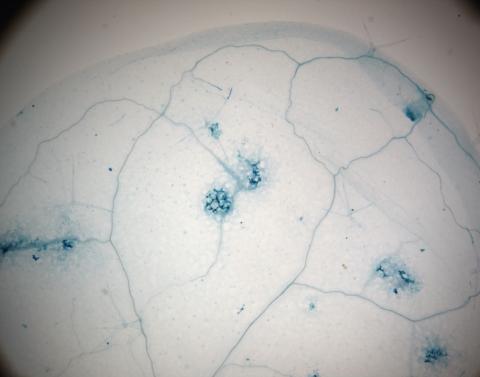

2781: Disease-resistant Arabidopsis leaf

2781: Disease-resistant Arabidopsis leaf

This is a magnified view of an Arabidopsis thaliana leaf a few days after being exposed to the pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. The plant from which this leaf was taken is genetically resistant to the pathogen. The spots in blue show areas of localized cell death where infection occurred, but it did not spread. Compare this response to that shown in Image 2782. Jeff Dangl has been funded by NIGMS to study the interactions between pathogens and hosts that allow or suppress infection.

Jeff Dangl, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

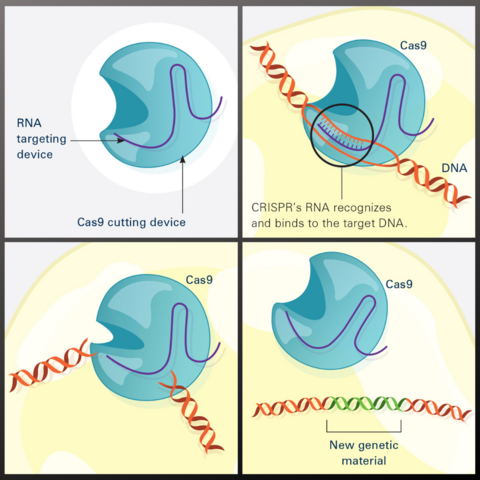

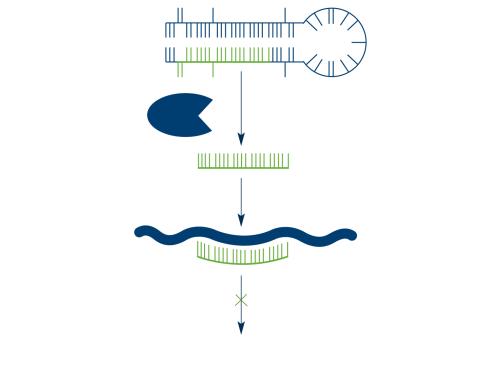

7036: CRISPR Illustration

7036: CRISPR Illustration

This illustration shows, in simplified terms, how the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used as a gene-editing tool.

Frame 1 shows the two components of the CRISPR system: a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA), and a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence).

In frame 2, the CRISPR machine locates the target DNA sequence once inserted into a cell.

In frame 3, the Cas9 enzyme cuts both strands of the DNA.

Frame 4 shows a repaired DNA strand with new genetic material that researchers can introduce, which the cell automatically incorporates into the gap when it repairs the broken DNA.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video.

Download the individual frames: Frame 1, Frame 2, Frame 3, and Frame 4.

Frame 1 shows the two components of the CRISPR system: a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA), and a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence).

In frame 2, the CRISPR machine locates the target DNA sequence once inserted into a cell.

In frame 3, the Cas9 enzyme cuts both strands of the DNA.

Frame 4 shows a repaired DNA strand with new genetic material that researchers can introduce, which the cell automatically incorporates into the gap when it repairs the broken DNA.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video.

Download the individual frames: Frame 1, Frame 2, Frame 3, and Frame 4.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

View Media

6983: Genetic mosaicism in fruit flies

6983: Genetic mosaicism in fruit flies

Fat tissue from the abdomen of a genetically mosaic adult fruit fly. Genetic mosaicism means that the fly has cells with different genotypes even though it formed from a single zygote. This specific mosaicism results in accumulation of a critical fly adipokine (blue-green) within the fat tissue cells that have reduced expression a key nutrient sensing gene (in left panel). The dotted line shows the cells lacking the gene that is present and functioning in the rest of the cells. Nuclei are labelled in magenta. This image was captured using a confocal microscope and shows a maximum intensity projection of many slices.

Related to images 6982, 6984, and 6985.

Related to images 6982, 6984, and 6985.

Akhila Rajan, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center

View Media

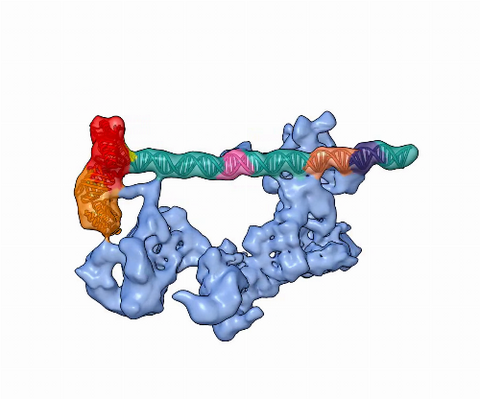

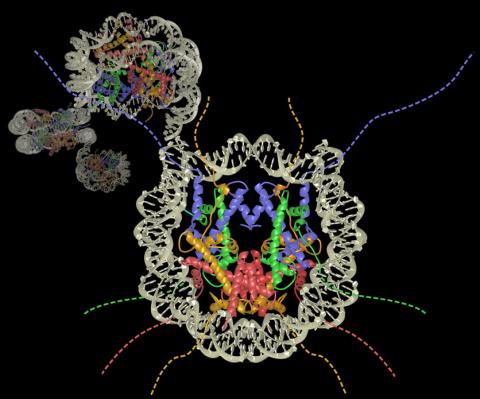

3597: DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC)

3597: DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC)

A study published in March 2012 used cryo-electron microscopy to determine the structure of the DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC), a semi-circular, protein complex (yellow) that recognizes and binds DNA to start the replication process. The ORC appears to wrap around and bend approximately 70 base pairs of double stranded DNA (red and blue). Also shown is the protein Cdc6 (green), which is also involved in the initiation of DNA replication. Related to video 3307 that shows the structure from different angles. From a Brookhaven National Laboratory news release, "Study Reveals How Protein Machinery Binds and Wraps DNA to Start Replication."

Huilin Li, Brookhaven National Laboratory

View Media

2513: Life of an AIDS virus

2513: Life of an AIDS virus

HIV is a retrovirus, a type of virus that carries its genetic material not as DNA but as RNA. Long before anyone had heard of HIV, researchers in labs all over the world studied retroviruses, tracing out their life cycle and identifying the key proteins the viruses use to infect cells. When HIV was identified as a retrovirus, these studies gave AIDS researchers an immediate jump-start. The previously identified viral proteins became initial drug targets. See images 2514 and 2515 for labeled versions of this illustration. Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

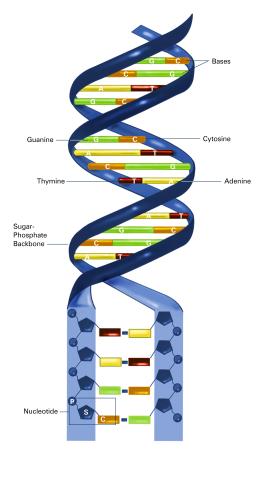

2542: Nucleotides make up DNA (with labels)

2542: Nucleotides make up DNA (with labels)

DNA consists of two long, twisted chains made up of nucleotides. Each nucleotide contains one base, one phosphate molecule, and the sugar molecule deoxyribose. The bases in DNA nucleotides are adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. See image 2541 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

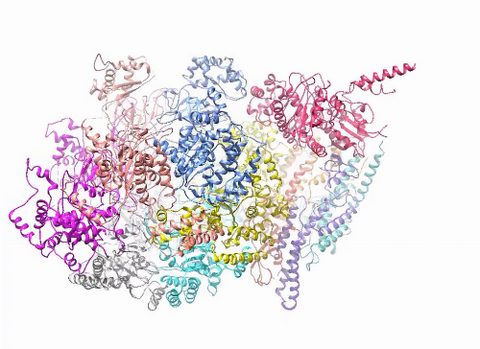

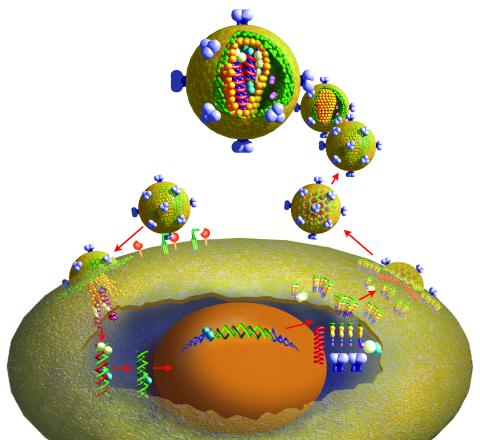

5730: Dynamic cryo-EM model of the human transcription preinitiation complex

5730: Dynamic cryo-EM model of the human transcription preinitiation complex

Gene transcription is a process by which information encoded in DNA is transcribed into RNA. It's essential for all life and requires the activity of proteins, called transcription factors, that detect where in a DNA strand transcription should start. In eukaryotes (i.e., those that have a nucleus and mitochondria), a protein complex comprising 14 different proteins is responsible for sniffing out transcription start sites and starting the process. This complex represents the core machinery to which an enzyme, named RNA polymerase, can bind to and read the DNA and transcribe it to RNA. Scientists have used cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to visualize the TFIID-RNA polymerase-DNA complex in unprecedented detail. This animation shows the different TFIID components as they contact DNA and recruit the RNA polymerase for gene transcription.

To learn more about the research that has shed new light on gene transcription, see this news release from Berkeley Lab.

Related to image 3766.

To learn more about the research that has shed new light on gene transcription, see this news release from Berkeley Lab.

Related to image 3766.

Eva Nogales, Berkeley Lab

View Media

2593: Precise development in the fruit fly embryo

2593: Precise development in the fruit fly embryo

This 2-hour-old fly embryo already has a blueprint for its formation, and the process for following it is so precise that the difference of just a few key molecules can change the plans. Here, blue marks a high concentration of Bicoid, a key signaling protein that directs the formation of the fly's head. It also regulates another important protein, Hunchback (green), that further maps the head and thorax structures and partitions the embryo in half (red is DNA). The yellow dots overlaying the embryo plot the concentration of Bicoid versus Hunchback proteins within each nucleus. The image illustrates the precision with which an embryo interprets and locates its halfway boundary, approaching limits set by simple physical principles. This image was a finalist in the 2008 Drosophila Image Award.

Thomas Gregor, Princeton University

View Media

2515: Life of an AIDS virus (with labels and stages)

2515: Life of an AIDS virus (with labels and stages)

HIV is a retrovirus, a type of virus that carries its genetic material not as DNA but as RNA. Long before anyone had heard of HIV, researchers in labs all over the world studied retroviruses, tracing out their life cycle and identifying the key proteins the viruses use to infect cells. When HIV was identified as a retrovirus, these studies gave AIDS researchers an immediate jump-start. The previously identified viral proteins became initial drug targets. See images 2513 and 2514 for other versions of this illustration. Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

3782: A multicolored fish scale 1

3782: A multicolored fish scale 1

Each of the colored specs in this image is a cell on the surface of a fish scale. To better understand how wounds heal, scientists have inserted genes that make cells brightly glow in different colors into the skin cells of zebrafish, a fish often used in laboratory research. The colors enable the researchers to track each individual cell, for example, as it moves to the location of a cut or scrape over the course of several days. These technicolor fish endowed with glowing skin cells dubbed "skinbow" provide important insight into how tissues recover and regenerate after an injury.

For more information on skinbow fish, see the Biomedical Beat blog post Visualizing Skin Regeneration in Real Time and a press release from Duke University highlighting this research. Related to image 3783.

For more information on skinbow fish, see the Biomedical Beat blog post Visualizing Skin Regeneration in Real Time and a press release from Duke University highlighting this research. Related to image 3783.

Chen-Hui Chen and Kenneth Poss, Duke University

View Media

2728: Sponge

2728: Sponge

Many of today's medicines come from products found in nature, such as this sponge found off the coast of Palau in the Pacific Ocean. Chemists have synthesized a compound called Palau'amine, which appears to act against cancer, bacteria and fungi. In doing so, they invented a new chemical technique that will empower the synthesis of other challenging molecules.

Phil Baran, Scripps Research Institute

View Media

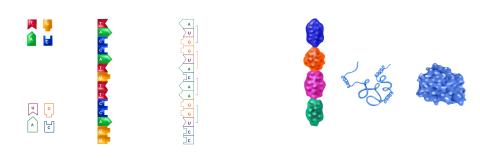

2509: From DNA to Protein

2509: From DNA to Protein

Nucleotides in DNA are copied into RNA, where they are read three at a time to encode the amino acids in a protein. Many parts of a protein fold as the amino acids are strung together.

See image 2510 for a labeled version of this illustration.

Featured in The Structures of Life.

See image 2510 for a labeled version of this illustration.

Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

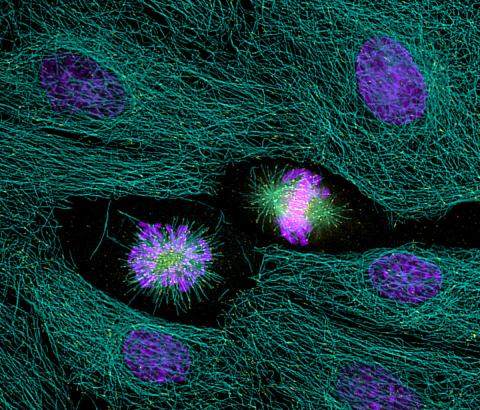

3445: Dividing cell in metaphase

3445: Dividing cell in metaphase

This image of a mammalian epithelial cell, captured in metaphase, was the winning image in the high- and super-resolution microscopy category of the 2012 GE Healthcare Life Sciences Cell Imaging Competition. The image shows microtubules (red), kinetochores (green) and DNA (blue). The DNA is fixed in the process of being moved along the microtubules that form the structure of the spindle.

The image was taken using the DeltaVision OMX imaging system, affectionately known as the "OMG" microscope, and was displayed on the NBC screen in New York's Times Square during the weekend of April 20-21, 2013. It was also part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

The image was taken using the DeltaVision OMX imaging system, affectionately known as the "OMG" microscope, and was displayed on the NBC screen in New York's Times Square during the weekend of April 20-21, 2013. It was also part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Jane Stout in the laboratory of Claire Walczak, Indiana University, GE Healthcare 2012 Cell Imaging Competition

View Media

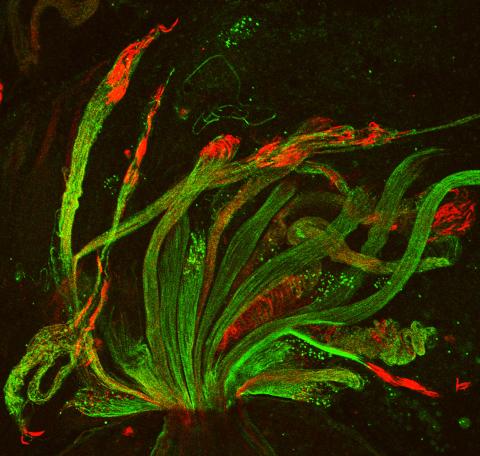

3590: Fruit fly spermatids

3590: Fruit fly spermatids

Developing spermatids (precursors of mature sperm cells) begin as small, round cells and mature into long-tailed, tadpole-shaped ones. In the sperm cell's head is the cell nucleus; in its tail is the power to outswim thousands of competitors to fertilize an egg. As seen in this microscopy image, fruit fly spermatids start out as groups of interconnected cells. A small lipid molecule called PIP2 helps spermatids tell their heads from their tails. Here, PIP2 (red) marks the nuclei and a cell skeleton-building protein called tubulin (green) marks the tails. When PIP2 levels are too low, some spermatids get mixed up and grow with their heads at the wrong end. Because sperm development is similar across species, studies in fruit flies could help researchers understand male infertility in humans.

Lacramioara Fabian, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada

View Media

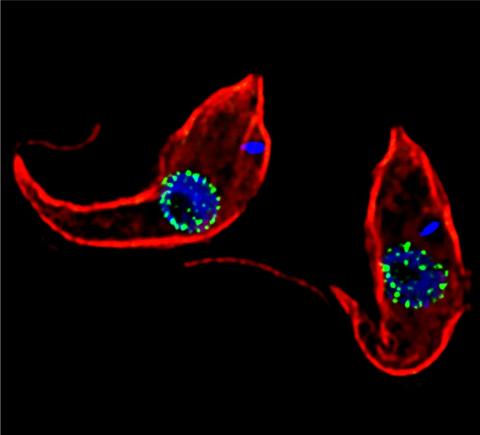

3765: Trypanosoma brucei, the cause of sleeping sickness

3765: Trypanosoma brucei, the cause of sleeping sickness

Trypanosoma brucei is a single-cell parasite that causes sleeping sickness in humans. Scientists have been studying trypanosomes for some time because of their negative effects on human and also animal health, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, because these organisms evolved on a separate path from those of animals and plants more than a billion years ago, researchers study trypanosomes to find out what traits they may harbor that are common to or different from those of other eukaryotes (i.e., those organisms having a nucleus and mitochondria). This image shows the T. brucei cell membrane in red, the DNA in the nucleus and kinetoplast (a structure unique to protozoans, including trypanosomes, which contains mitochondrial DNA) in blue and nuclear pore complexes (which allow molecules to pass into or out of the nucleus) in green. Scientists have found that the trypanosome nuclear pore complex has a unique mechanism by which it attaches to the nuclear envelope. In addition, the trypanosome nuclear pore complex differs from those of other eukaryotes because its components have a near-complete symmetry, and it lacks almost all of the proteins that in other eukaryotes studied so far are required to assemble the pore.

Michael Rout, Rockefeller University

View Media

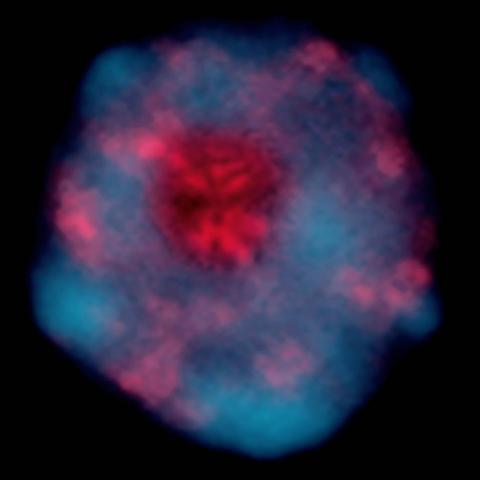

2318: Gene silencing

2318: Gene silencing

Pretty in pink, the enzyme histone deacetylase (HDA6) stands out against a background of blue-tinted DNA in the nucleus of an Arabidopsis plant cell. Here, HDA6 concentrates in the nucleolus (top center), where ribosomal RNA genes reside. The enzyme silences the ribosomal RNA genes from one parent while those from the other parent remain active. This chromosome-specific silencing of ribosomal RNA genes is an unusual phenomenon observed in hybrid plants.

Olga Pontes and Craig Pikaard, Washington University

View Media

2429: Highlighted cells

2429: Highlighted cells

The cytoskeleton (green) and DNA (purple) are highlighed in these cells by immunofluorescence.

Torsten Wittmann, Scripps Research Institute

View Media

5764: Host infection stimulates antibiotic resistance

5764: Host infection stimulates antibiotic resistance

This illustration shows pathogenic bacteria behave like a Trojan horse: switching from antibiotic susceptibility to resistance during infection. Salmonella are vulnerable to antibiotics while circulating in the blood (depicted by fire on red blood cell) but are highly resistant when residing within host macrophages. This leads to treatment failure with the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria.

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call, and the research was funded in part by NIGMS.

View Media

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call, and the research was funded in part by NIGMS.

2556: Dicer generates microRNAs

2556: Dicer generates microRNAs

The enzyme Dicer generates microRNAs by chopping larger RNA molecules into tiny Velcro®-like pieces. MicroRNAs stick to mRNA molecules and prevent the mRNAs from being made into proteins. See image 2557 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

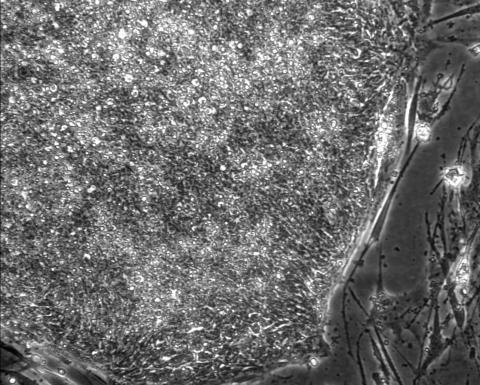

2603: Induced stem cells from adult skin 01

2603: Induced stem cells from adult skin 01

These cells are induced stem cells made from human adult skin cells that were genetically reprogrammed to mimic embryonic stem cells. The induced stem cells were made potentially safer by removing the introduced genes and the viral vector used to ferry genes into the cells, a loop of DNA called a plasmid. The work was accomplished by geneticist Junying Yu in the laboratory of James Thomson, a University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health professor and the director of regenerative biology for the Morgridge Institute for Research.

James Thomson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

2417: Fly by night

2417: Fly by night

This fruit fly expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the same pattern as the period gene, a gene that regulates circadian rhythm and is expressed in all sensory neurons on the surface of the fly.

Jay Hirsh, University of Virginia

View Media

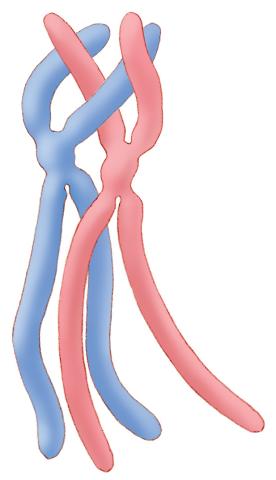

1315: Chromosomes before crossing over

1315: Chromosomes before crossing over

Duplicated pair of chromosomes lined up and ready to cross over.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

2741: Nucleosome

2741: Nucleosome

Like a strand of white pearls, DNA wraps around an assembly of special proteins called histones (colored) to form the nucleosome, a structure responsible for regulating genes and condensing DNA strands to fit into the cell's nucleus. Researchers once thought that nucleosomes regulated gene activity through their histone tails (dotted lines), but a 2010 study revealed that the structures' core also plays a role. The finding sheds light on how gene expression is regulated and how abnormal gene regulation can lead to cancer.

Karolin Luger, Colorado State University

View Media

3656: Fruit fly ovary_2

3656: Fruit fly ovary_2

A fruit fly ovary, shown here, contains as many as 20 eggs. Fruit flies are not merely tiny insects that buzz around overripe fruit--they are a venerable scientific tool. Research on the flies has shed light on many aspects of human biology, including biological rhythms, learning, memory and neurodegenerative diseases. Another reason fruit flies are so useful in a lab (and so successful in fruit bowls) is that they reproduce rapidly. About three generations can be studied in a single month. Related to image 3607.

Denise Montell, University of California, Santa Barbara

View Media

2443: Mapping human genetic variation

2443: Mapping human genetic variation

This map paints a colorful portrait of human genetic variation around the world. Researchers analyzed the DNA of 485 people and tinted the genetic types in different colors to produce one of the most detailed maps of its kind ever made. The map shows that genetic variation decreases with increasing distance from Africa, which supports the idea that humans originated in Africa, spread to the Middle East, then to Asia and Europe, and finally to the Americas. The data also offers a rich resource that scientists could use to pinpoint the genetic basis of diseases prevalent in diverse populations. Featured in the March 19, 2008, issue of Biomedical Beat.

Noah Rosenberg and Martin Soave, University of Michigan

View Media

6771: Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito larvae

6771: Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito larvae

Mosquito larvae with genes edited by CRISPR swimming in water. This species of mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, can transmit West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and avian malaria, among other diseases. The researchers who took this video optimized the gene-editing tool CRISPR for Culex quinquefasciatus that could ultimately help stop the mosquitoes from spreading pathogens. The work is described in the Nature Communications paper "Optimized CRISPR tools and site-directed transgenesis towards gene drive development in Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes" by Feng et al. Related to images 6769 and 6770.

Valentino Gantz, University of California, San Diego.

View Media

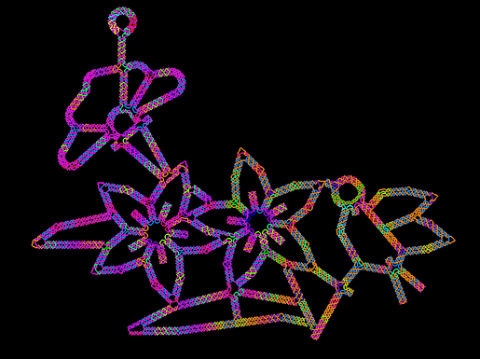

3689: Computer sketch of bird-and-flower DNA origami

3689: Computer sketch of bird-and-flower DNA origami

A computer-generated sketch of a DNA origami folded into a flower-and-bird structure. See also related image 3690.

Hao Yan, Arizona State University

View Media

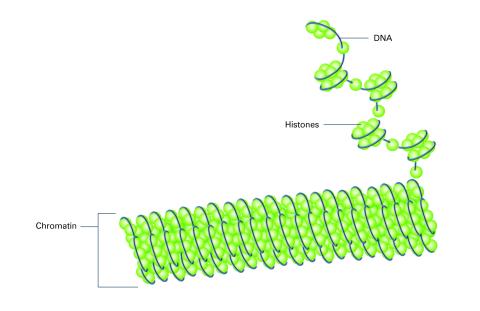

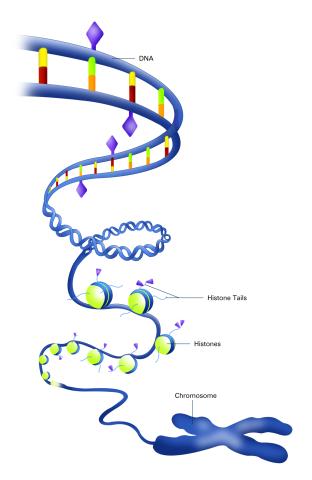

2561: Histones in chromatin (with labels)

2561: Histones in chromatin (with labels)

Histone proteins loop together with double-stranded DNA to form a structure that resembles beads on a string. See image 2560 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2563: Epigenetic code (with labels)

2563: Epigenetic code (with labels)

The "epigenetic code" controls gene activity with chemical tags that mark DNA (purple diamonds) and the "tails" of histone proteins (purple triangles). These markings help determine whether genes will be transcribed by RNA polymerase. Genes hidden from access to RNA polymerase are not expressed. See image 2562 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

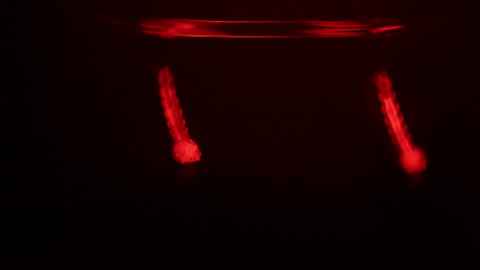

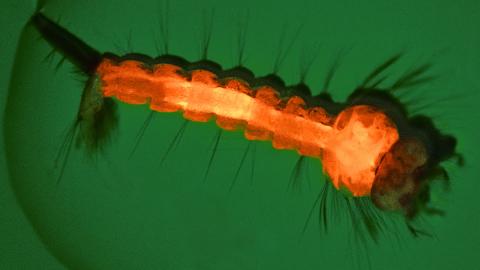

6769: Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito larva

6769: Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito larva

A mosquito larva with genes edited by CRISPR. The red-orange glow is a fluorescent protein used to track the edits. This species of mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, can transmit West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and avian malaria, among other diseases. The researchers who took this image developed a gene-editing toolkit for Culex quinquefasciatus that could ultimately help stop the mosquitoes from spreading pathogens. The work is described in the Nature Communications paper "Optimized CRISPR tools and site-directed transgenesis towards gene drive development in Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes" by Feng et al. Related to image 6770 and video 6771.

Valentino Gantz, University of California, San Diego.

View Media