Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

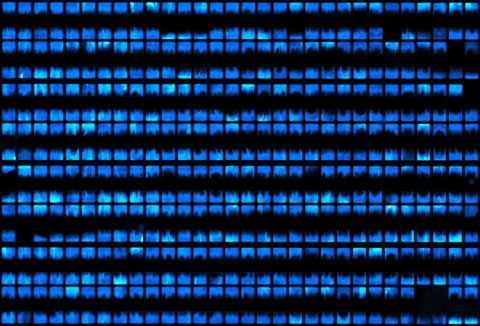

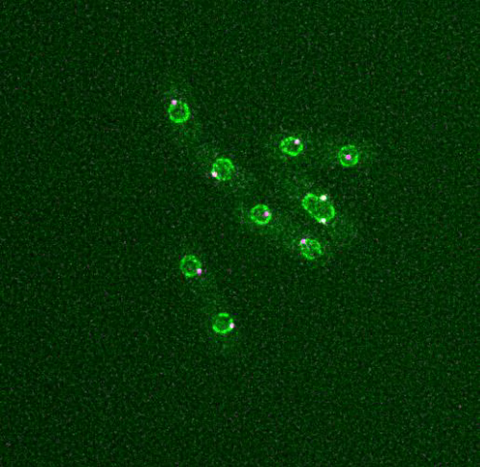

3266: Biopixels

3266: Biopixels

Bioengineers were able to coax bacteria to blink in unison on microfluidic chips. This image shows a small chip with about 500 blinking bacterial colonies or biopixels. Related to images 3265 and 3268. From a UC San Diego news release, "Researchers create living 'neon signs' composed of millions of glowing bacteria."

Jeff Hasty Lab, UC San Diego

View Media

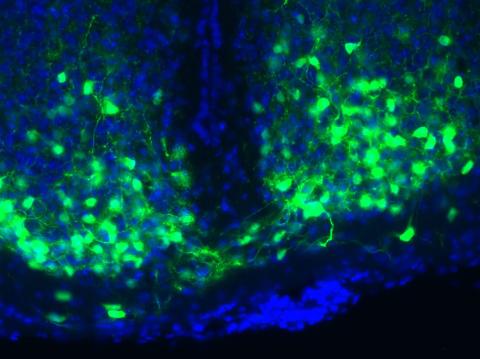

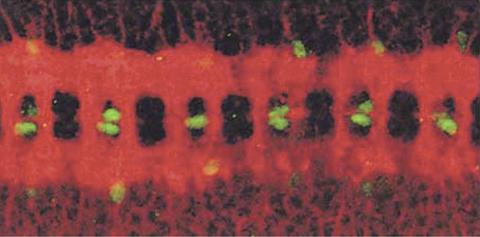

3547: Master clock of the mouse brain

3547: Master clock of the mouse brain

An image of the area of the mouse brain that serves as the 'master clock,' which houses the brain's time-keeping neurons. The nuclei of the clock cells are shown in blue. A small molecule called VIP, shown in green, enables neurons in the central clock in the mammalian brain to synchronize.

Erik Herzog, Washington University in St. Louis

View Media

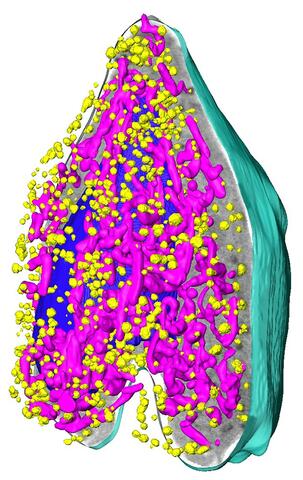

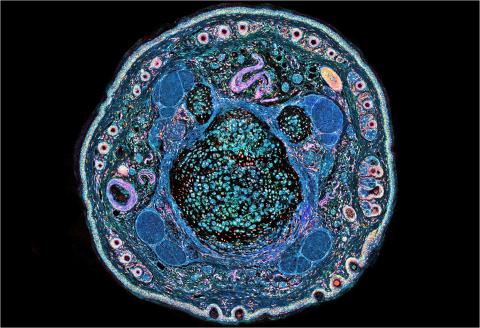

6605: Soft X-ray tomography of a pancreatic beta cell

6605: Soft X-ray tomography of a pancreatic beta cell

A color-coded, 3D model of a rat pancreatic β cell. This type of cell produces insulin, a hormone that helps regulate blood sugar. Visible are mitochondria (pink), insulin vesicles (yellow), the nucleus (dark blue), and the plasma membrane (teal). This model was created based on soft X-ray tomography (SXT) images.

Carolyn Larabell, University of California, San Francisco.

View Media

1091: Nerve and glial cells in fruit fly embryo

1091: Nerve and glial cells in fruit fly embryo

Glial cells (stained green) in a fruit fly developing embryo have survived thanks to a signaling pathway initiated by neighboring nerve cells (stained red).

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

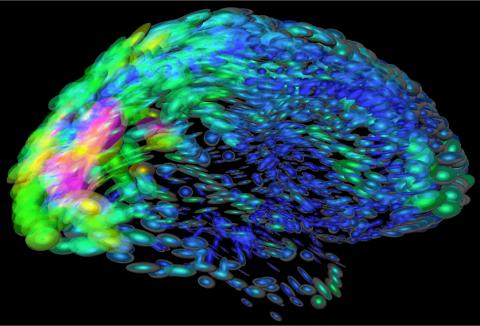

2419: Mapping brain differences

2419: Mapping brain differences

This image of the human brain uses colors and shapes to show neurological differences between two people. The blurred front portion of the brain, associated with complex thought, varies most between the individuals. The blue ovals mark areas of basic function that vary relatively little. Visualizations like this one are part of a project to map complex and dynamic information about the human brain, including genes, enzymes, disease states, and anatomy. The brain maps represent collaborations between neuroscientists and experts in math, statistics, computer science, bioinformatics, imaging, and nanotechnology.

Arthur Toga, University of California, Los Angeles

View Media

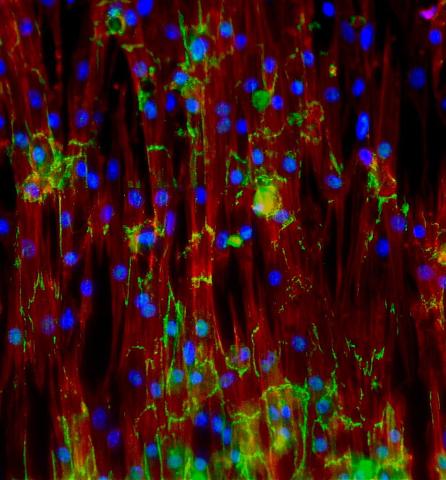

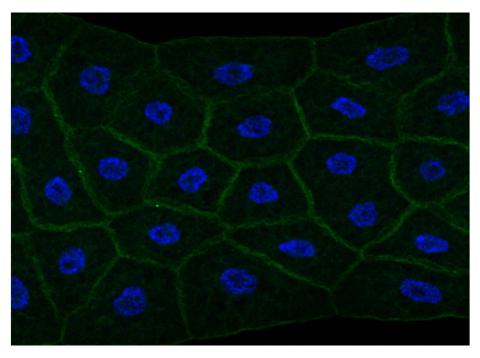

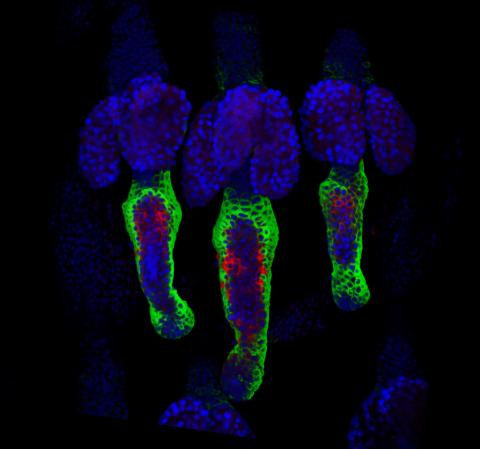

3282: Mouse heart muscle cells

3282: Mouse heart muscle cells

This image shows neonatal mouse heart cells. These cells were grown in the lab on a chip that aligns the cells in a way that mimics what is normally seen in the body. Green shows the protein N-cadherin, which indicates normal connections between cells. Red indicates the muscle protein actin, and blue indicates the cell nuclei. The work shown here was part of a study attempting to grow heart tissue in the lab to repair damage after a heart attack. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Related to images 3281 and 3283.

Kara McCloskey lab, University of California, Merced, via CIRM

View Media

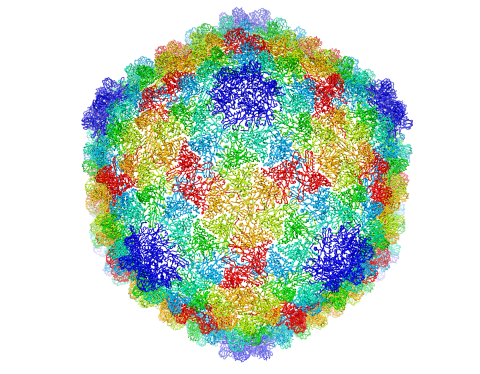

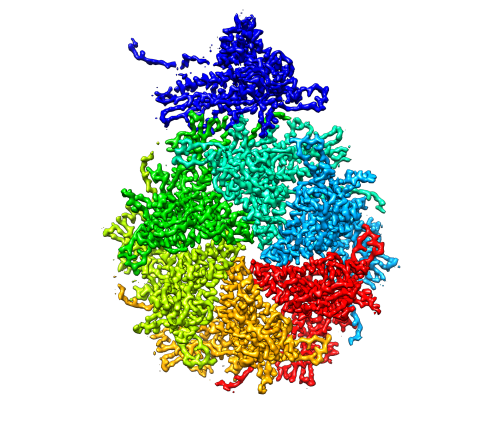

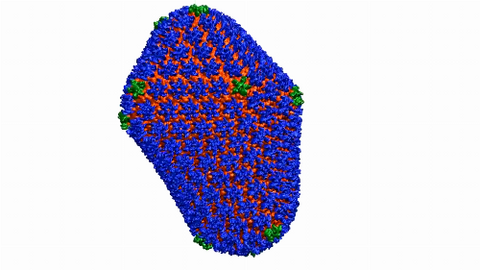

5874: Bacteriophage P22 capsid

5874: Bacteriophage P22 capsid

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has the power to capture details of proteins and other small biological structures at the molecular level. This image shows proteins in the capsid, or outer cover, of bacteriophage P22, a virus that infects the Salmonella bacteria. Each color shows the structure and position of an individual protein in the capsid. Thousands of cryo-EM scans capture the structure and shape of all the individual proteins in the capsid and their position relative to other proteins. A computer model combines these scans into the three-dimension image shown here. Related to image 5875.

Dr. Wah Chiu, Baylor College of Medicine

View Media

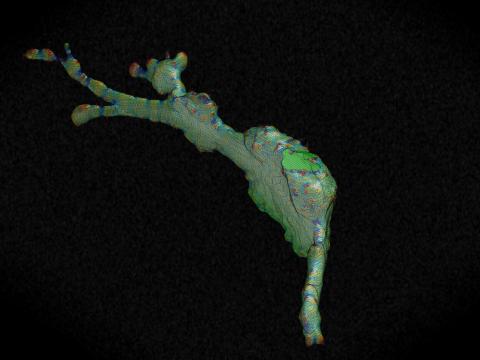

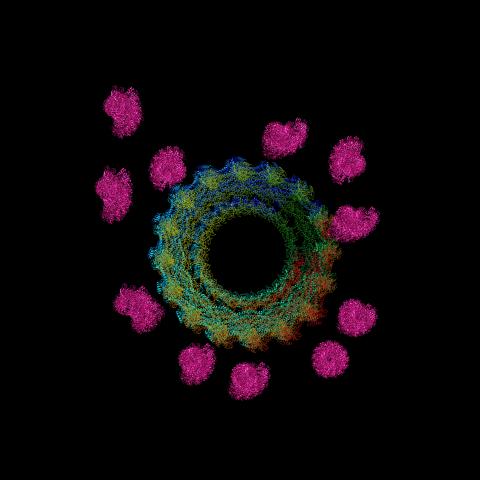

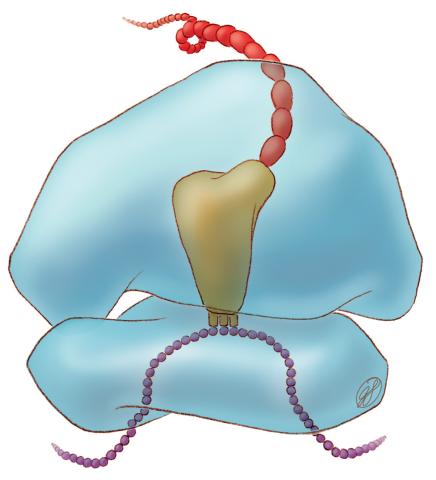

6571: Actin filaments bundled around the dynamin helical polymer

6571: Actin filaments bundled around the dynamin helical polymer

Multiple actin filaments (magenta) are organized around a dynamin helical polymer (rainbow colored) in this model derived from cryo-electron tomography. By bundling actin, dynamin increases the strength of a cell’s skeleton and plays a role in cell-cell fusion, a process involved in conception, development, and regeneration.

Elizabeth Chen, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

View Media

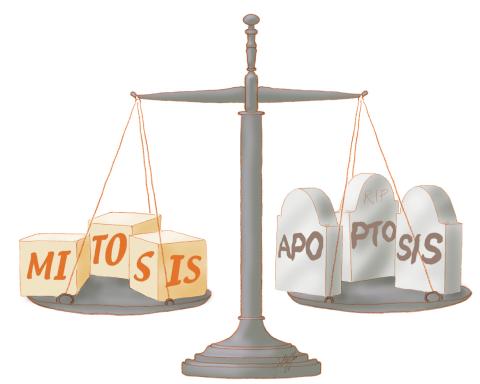

1336: Life in balance

1336: Life in balance

Mitosis creates cells, and apoptosis kills them. The processes often work together to keep us healthy.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

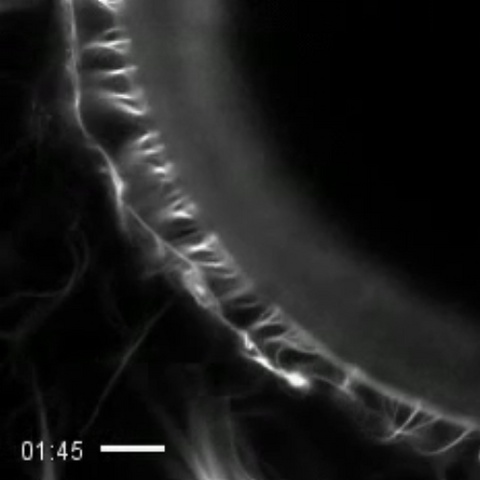

3616: Weblike sheath covering developing egg chambers in a giant grasshopper

3616: Weblike sheath covering developing egg chambers in a giant grasshopper

The lubber grasshopper, found throughout the southern United States, is frequently used in biology classes to teach students about the respiratory system of insects. Unlike mammals, which have red blood cells that carry oxygen throughout the body, insects have breathing tubes that carry air through their exoskeleton directly to where it's needed. This image shows the breathing tubes embedded in the weblike sheath cells that cover developing egg chambers.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Kevin Edwards, Johny Shajahan, and Doug Whitman, Illinois State University.

View Media

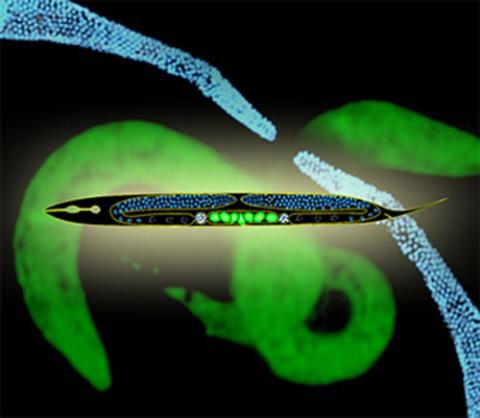

2333: Worms and human infertility

2333: Worms and human infertility

This montage of tiny, transparent C. elegans--or roundworms--may offer insight into understanding human infertility. Researchers used fluorescent dyes to label the worm cells and watch the process of sex cell division, called meiosis, unfold as nuclei (blue) move through the tube-like gonads. Such visualization helps the scientists identify mechanisms that enable these roundworms to reproduce successfully. Because meiosis is similar in all sexually reproducing organisms, what the scientists learn could apply to humans.

Abby Dernburg, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

View Media

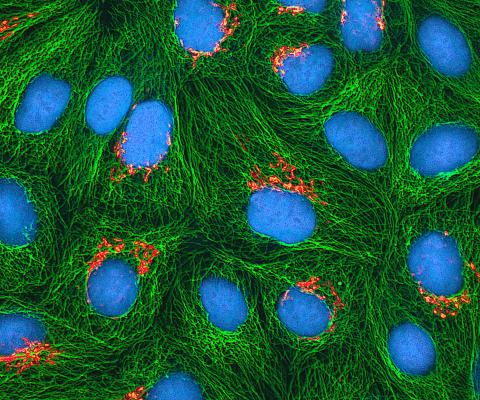

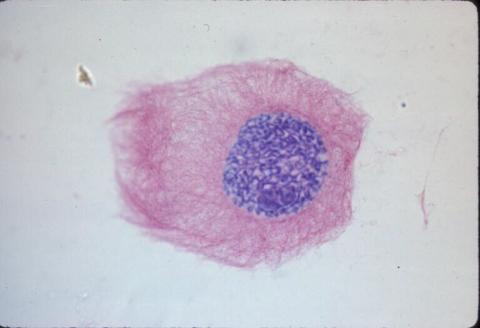

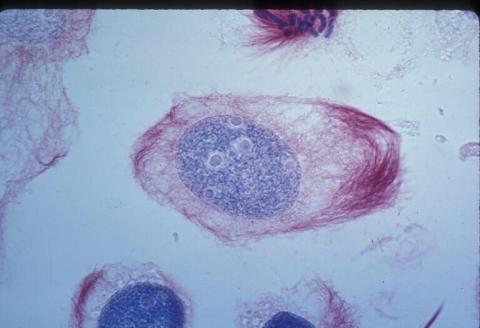

3522: HeLa cells

3522: HeLa cells

Multiphoton fluorescence image of cultured HeLa cells with a fluorescent protein targeted to the Golgi apparatus (orange), microtubules (green) and counterstained for DNA (cyan). Nikon RTS2000MP custom laser scanning microscope. See related images 3518, 3519, 3520, 3521.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

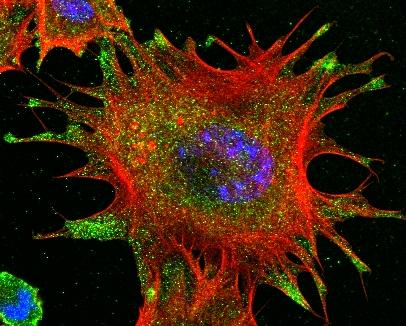

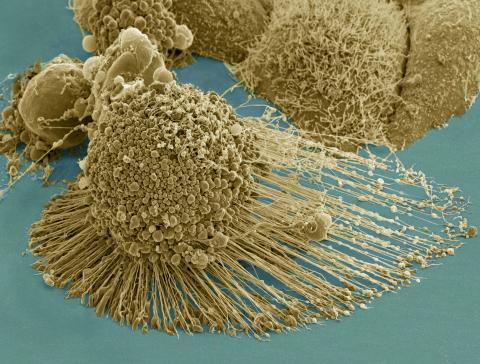

3331: mDia1 antibody staining- 02

3331: mDia1 antibody staining- 02

Cells move forward with lamellipodia and filopodia supported by networks and bundles of actin filaments. Proper, controlled cell movement is a complex process. Recent research has shown that an actin-polymerizing factor called the Arp2/3 complex is the key component of the actin polymerization engine that drives amoeboid cell motility. ARPC3, a component of the Arp2/3 complex, plays a critical role in actin nucleation. In this photo, the ARPC3-/- fibroblast cells were fixed and stained with Alexa 546 phalloidin for F-actin (red), mDia1 (green), and DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). In ARPC3-/- fibroblast cells, mDia1 is localized at the tips of the filopodia-like structures. Related to images 3328, 3329, 3330, 3332, and 3333.

Rong Li and Praveen Suraneni, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

View Media

3737: A bundle of myelinated peripheral nerve cells (axons)

3737: A bundle of myelinated peripheral nerve cells (axons)

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is most prevalent in connective tissues but also is present between the stems (axons) of nerve cells. The axons of nerve cells are surrounded by the ECM encasing myelin-supplying Schwann cells, which insulate the axons to help speed the transmission of electric nerve impulses along the axons.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

1292: Smooth ER

1292: Smooth ER

The endoplasmic reticulum comes in two types: Rough ER is covered with ribosomes and prepares newly made proteins; smooth ER specializes in making lipids and breaking down toxic molecules.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

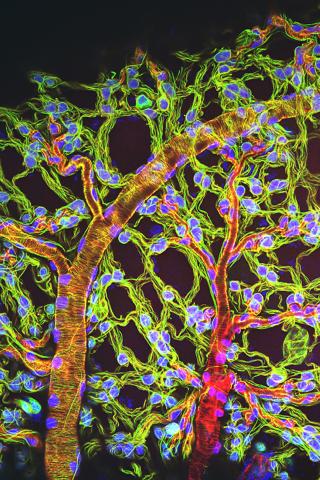

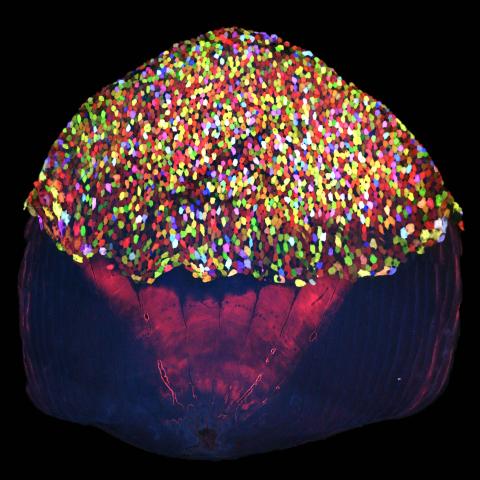

3783: A multicolored fish scale 2

3783: A multicolored fish scale 2

Each of the tiny colored specs in this image is a cell on the surface of a fish scale. To better understand how wounds heal, scientists have inserted genes that make cells brightly glow in different colors into the skin cells of zebrafish, a fish often used in laboratory research. The colors enable the researchers to track each individual cell, for example, as it moves to the location of a cut or scrape over the course of several days. These technicolor fish endowed with glowing skin cells dubbed "skinbow" provide important insight into how tissues recover and regenerate after an injury.

For more information on skinbow fish, see the Biomedical Beat blog post Visualizing Skin Regeneration in Real Time and a press release from Duke University highlighting this research. Related to image 3782.

For more information on skinbow fish, see the Biomedical Beat blog post Visualizing Skin Regeneration in Real Time and a press release from Duke University highlighting this research. Related to image 3782.

Chen-Hui Chen and Kenneth Poss, Duke University

View Media

5875: Bacteriophage P22 capsid, detail

5875: Bacteriophage P22 capsid, detail

Detail of a subunit of the capsid, or outer cover, of bacteriophage P22, a virus that infects the Salmonella bacteria. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) was used to capture details of the capsid proteins, each shown here in a separate color. Thousands of cryo-EM scans capture the structure and shape of all the individual proteins in the capsid and their position relative to other proteins. A computer model combines these scans into the image shown here. Related to image 5874.

Dr. Wah Chiu, Baylor College of Medicine

View Media

1281: Translation

1281: Translation

Ribosomes manufacture proteins based on mRNA instructions. Each ribosome reads mRNA, recruits tRNA molecules to fetch amino acids, and assembles the amino acids in the proper order.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

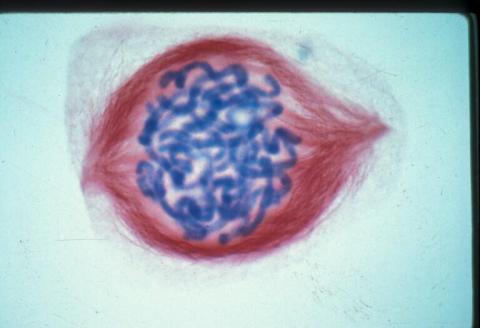

1015: Lily mitosis 05

1015: Lily mitosis 05

A light microscope image of a cell from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue. Here, condensed chromosomes are clearly visible.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

3494: How cilia do the wave

3494: How cilia do the wave

Thin, hair-like biological structures called cilia are tiny but mighty. Each one, made up of more than 600 different proteins, works together with hundreds of others in a tightly-packed layer to move like a crowd at a ball game doing "the wave." Their synchronized motion helps sweep mucus from the lungs and usher eggs from the ovaries into the uterus. By controlling how fluid flows around an embryo, cilia also help ensure that organs like the heart develop on the correct side of your body.

Zvonimir Dogic, Brandeis University

View Media

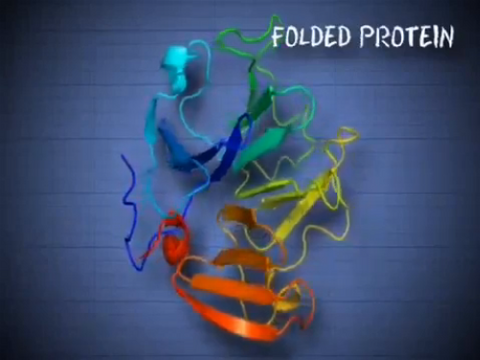

6602: See how immune cell acid destroys bacterial proteins

6602: See how immune cell acid destroys bacterial proteins

This animation shows the effect of exposure to hypochlorous acid, which is found in certain types of immune cells, on bacterial proteins. The proteins unfold and stick to one another, leading to cell death.

American Chemistry Council

View Media

1013: Lily mitosis 03

1013: Lily mitosis 03

A light microscope image of a cell from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

2757: Draper, shown in the fatbody of a Drosophila melanogaster larva

2757: Draper, shown in the fatbody of a Drosophila melanogaster larva

The fly fatbody is a nutrient storage and mobilization organ akin to the mammalian liver. The engulfment receptor Draper (green) is located at the cell surface of fatbody cells. The cell nuclei are shown in blue.

Christina McPhee and Eric Baehrecke, University of Massachusetts Medical School

View Media

3592: Math from the heart

3592: Math from the heart

Watch a cell ripple toward a beam of light that turns on a movement-related protein.

View Media

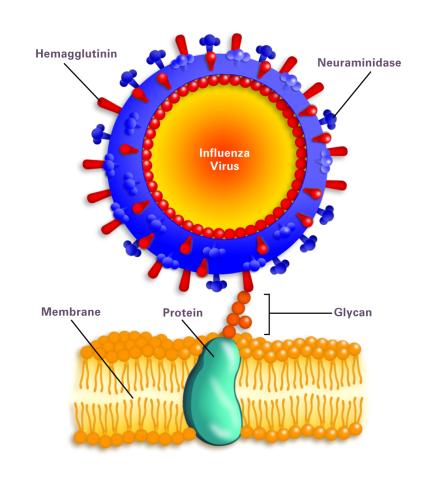

2505: Influenza virus attaches to host membrane (with labels)

2505: Influenza virus attaches to host membrane (with labels)

Influenza A infects a host cell when hemagglutinin grips onto glycans on its surface. Neuraminidase, an enzyme that chews sugars, helps newly made virus particles detach so they can infect other cells. Related to 213.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

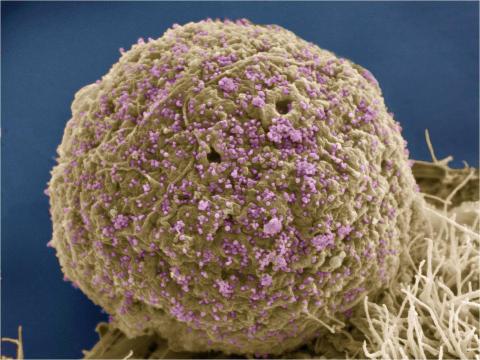

3386: HIV Infected Cell

3386: HIV Infected Cell

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), shown here as tiny purple spheres, causes the disease known as AIDS (for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). HIV can infect multiple cells in your body, including brain cells, but its main target is a cell in the immune system called the CD4 lymphocyte (also called a T-cell or CD4 cell).

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

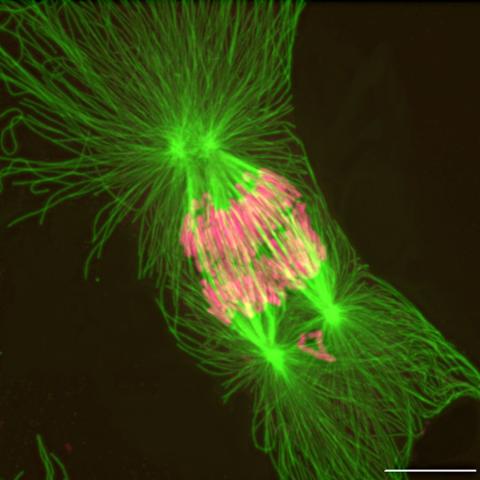

2739: Tetrapolar mitosis

2739: Tetrapolar mitosis

This image shows an abnormal, tetrapolar mitosis. Chromosomes are highlighted pink. The cells shown are S3 tissue cultured cells from Xenopus laevis, African clawed frog.

Gary Gorbsky, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation

View Media

6519: Human fibroblast undergoing cell division

6519: Human fibroblast undergoing cell division

During cell division, cells physically divide after separating their genetic material to create two daughter cells that are genetically identical to the parent cell. This process is important so that new cells can grow and develop. In this image, a human fibroblast cell—a type of connective tissue cell that plays a key role in wound healing and tissue repair—is dividing into two daughter cells. A cell protein called actin appears gray, the myosin II (part of the family of motor proteins responsible for muscle contractions) appears green, and DNA appears magenta.

Nilay Taneja, Vanderbilt University, and Dylan T. Burnette, Ph.D., Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

View Media

3395: NCMIR mouse tail

3395: NCMIR mouse tail

Stained cross section of a mouse tail.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

6601: Atomic-level structure of the HIV capsid

6601: Atomic-level structure of the HIV capsid

This animation shows atoms of the HIV capsid, the shell that encloses the virus's genetic material. Scientists determined the exact structure of the capsid using a variety of imaging techniques and analyses. They then entered this data into a supercomputer to produce this image. Related to image 3477.

Juan R. Perilla and the Theoretical and Computational Biophysics Group, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

View Media

1012: Lily mitosis 02

1012: Lily mitosis 02

A light microscope image of a cell from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

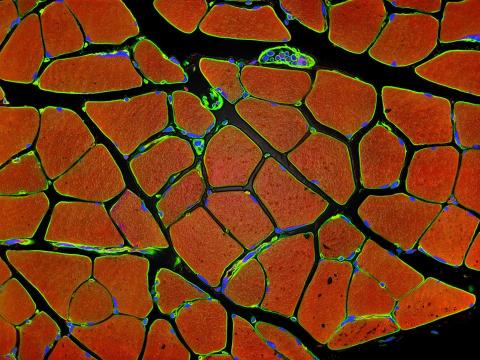

3677: Human skeletal muscle

3677: Human skeletal muscle

Cross section of human skeletal muscle. Image taken with a confocal fluorescent light microscope.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

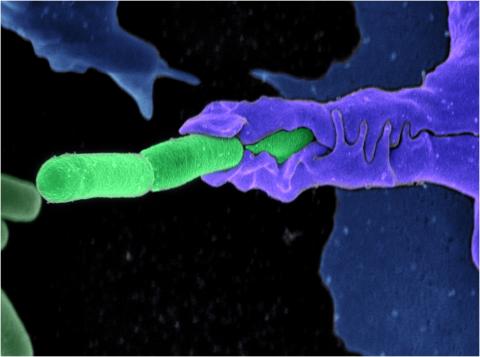

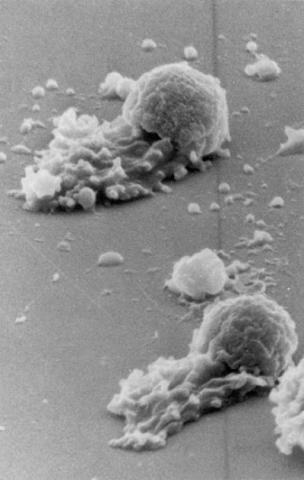

3612: Anthrax bacteria (green) being swallowed by an immune system cell

3612: Anthrax bacteria (green) being swallowed by an immune system cell

Multiple anthrax bacteria (green) being enveloped by an immune system cell (purple). Anthrax bacteria live in soil and form dormant spores that can survive for decades. When animals eat or inhale these spores, the bacteria activate and rapidly increase in number. Today, a highly effective and widely used vaccine has made the disease uncommon in domesticated animals and rare in humans.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Camenzind G. Robinson, Sarah Guilman, and Arthur Friedlander, United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases

View Media

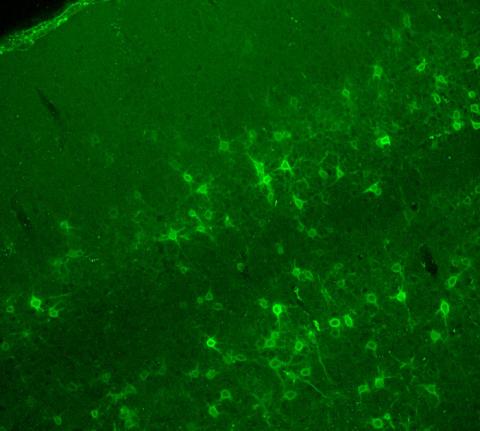

3742: Confocal microscopy of perineuronal nets in the brain 2

3742: Confocal microscopy of perineuronal nets in the brain 2

The photo shows a confocal microscopy image of perineuronal nets (PNNs), which are specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) structures in the brain. The PNN surrounds some nerve cells in brain regions including the cortex, hippocampus and thalamus. Researchers study the PNN to investigate their involvement stabilizing the extracellular environment and forming nets around nerve cells and synapses in the brain. Abnormalities in the PNNs have been linked to a variety of disorders, including epilepsy and schizophrenia, and they limit a process called neural plasticity in which new nerve connections are formed. To visualize the PNNs, researchers labeled them with Wisteria floribunda agglutinin (WFA)-fluorescein. Related to image 3741.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

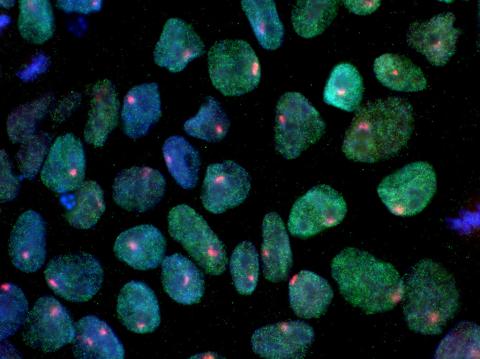

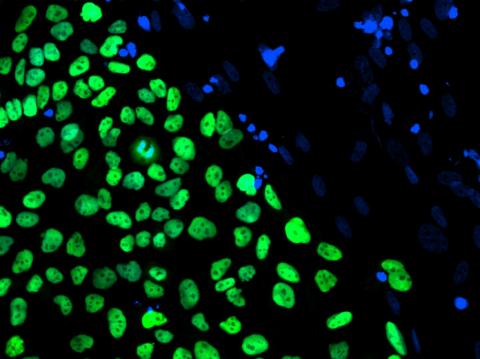

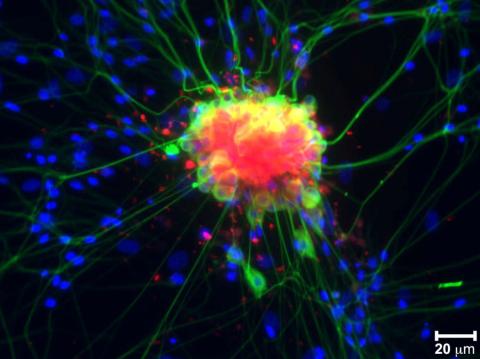

3279: Induced pluripotent stem cells from skin 02

3279: Induced pluripotent stem cells from skin 02

These induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) were derived from a woman's skin. Blue show nuclei. Green show a protein found in iPS cells but not in skin cells (NANOG). The red dots show the inactivated X chromosome in each cell. These cells can develop into a variety of cell types. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Related to image 3278.

Kathrin Plath lab, University of California, Los Angeles, via CIRM

View Media

6776: Tracking cells in a gastrulating zebrafish embryo

6776: Tracking cells in a gastrulating zebrafish embryo

During development, a zebrafish embryo is transformed from a ball of cells into a recognizable body plan by sweeping convergence and extension cell movements. This process is called gastrulation. Each line in this video represents the movement of a single zebrafish embryo cell over the course of 3 hours. The video was created using time-lapse confocal microscopy. Related to image 6775.

Liliana Solnica-Krezel, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

View Media

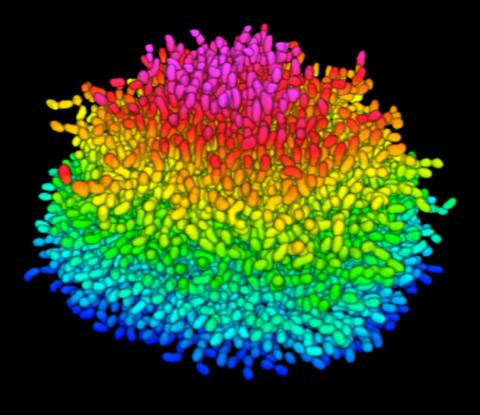

5825: A Growing Bacterial Biofilm

5825: A Growing Bacterial Biofilm

A growing Vibrio cholerae (cholera) biofilm. Cholera bacteria form colonies called biofilms that enable them to resist antibiotic therapy within the body and other challenges to their growth.

Each slightly curved comma shape represents an individual bacterium from assembled confocal microscopy images. Different colors show each bacterium’s position in the biofilm in relation to the surface on which the film is growing.

Each slightly curved comma shape represents an individual bacterium from assembled confocal microscopy images. Different colors show each bacterium’s position in the biofilm in relation to the surface on which the film is growing.

Jing Yan, Ph.D., and Bonnie Bassler, Ph.D., Department of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ.

View Media

3519: HeLa cells

3519: HeLa cells

Scanning electron micrograph of an apoptotic HeLa cell. Zeiss Merlin HR-SEM. See related images 3518, 3520, 3521, 3522.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media

3275: Human embryonic stem cells on feeder cells

3275: Human embryonic stem cells on feeder cells

The nuclei stained green highlight human embryonic stem cells grown under controlled conditions in a laboratory. Blue represents the DNA of surrounding, supportive feeder cells. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. See related image 3724.

Julie Baker lab, Stanford University School of Medicine, via CIRM

View Media

3497: Wound healing in process

3497: Wound healing in process

Wound healing requires the action of stem cells. In mice that lack the Sept2/ARTS gene, stem cells involved in wound healing live longer and wounds heal faster and more thoroughly than in normal mice. This confocal microscopy image from a mouse lacking the Sept2/ARTS gene shows a tail wound in the process of healing. See more information in the article in Science.

Related to images 3498 and 3500.

Related to images 3498 and 3500.

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

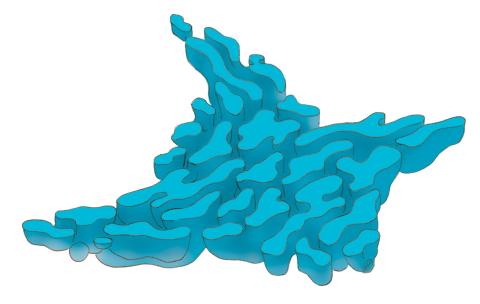

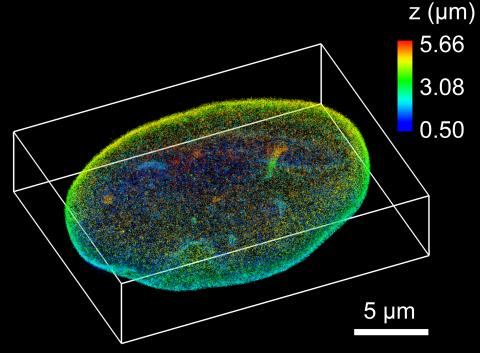

6572: Nuclear Lamina

6572: Nuclear Lamina

The 3D single-molecule super-resolution reconstruction of the entire nuclear lamina in a HeLa cell was acquired using the TILT3D platform. TILT3D combines a tilted light sheet with point-spread function (PSF) engineering to provide a flexible imaging platform for 3D single-molecule super-resolution imaging in mammalian cells.

See 6573 for 3 separate views of this structure.

See 6573 for 3 separate views of this structure.

Anna-Karin Gustavsson, Ph.D.

View Media

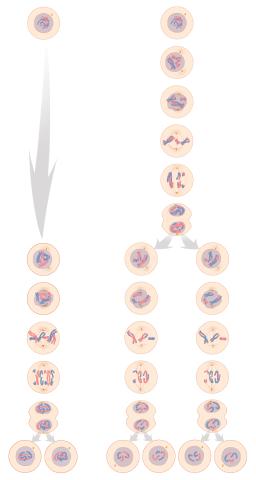

1333: Mitosis and meiosis compared

1333: Mitosis and meiosis compared

Meiosis is used to make sperm and egg cells. During meiosis, a cell's chromosomes are copied once, but the cell divides twice. During mitosis, the chromosomes are copied once, and the cell divides once. For simplicity, cells are illustrated with only three pairs of chromosomes. See image 6788 for a labeled version of this illustration.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

6795: Dividing yeast cells with nuclear envelopes and spindle pole bodies

6795: Dividing yeast cells with nuclear envelopes and spindle pole bodies

Time-lapse video of yeast cells undergoing cell division. Nuclear envelopes are shown in green, and spindle pole bodies, which help pull apart copied genetic information, are shown in magenta. This video was captured using wide-field microscopy with deconvolution.

Related to images 6791, 6792, 6793, 6794, 6797, 6798, and video 6796.

Related to images 6791, 6792, 6793, 6794, 6797, 6798, and video 6796.

Alaina Willet, Kathy Gould’s lab, Vanderbilt University.

View Media

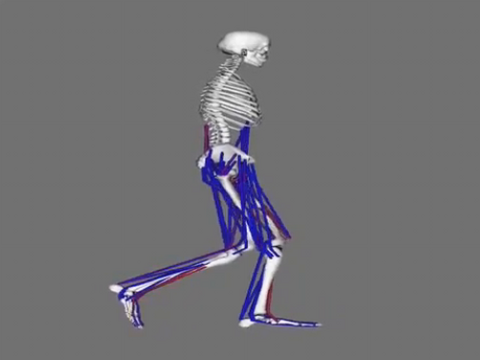

6598: Simulation of leg muscles moving

6598: Simulation of leg muscles moving

When we walk, muscles and nerves interact in intricate ways. This simulation, which is based on data from a six-foot-tall man, shows these interactions.

Chand John and Eran Guendelman, Stanford University

View Media

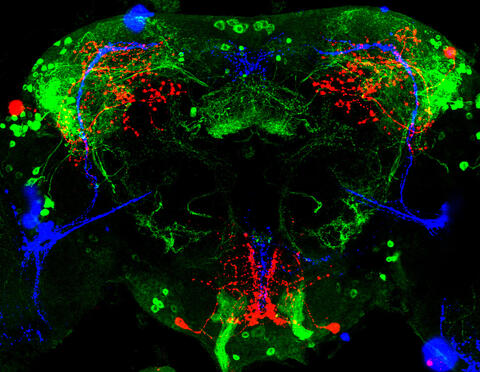

3754: Circadian rhythm neurons in the fruit fly brain

3754: Circadian rhythm neurons in the fruit fly brain

Some nerve cells (neurons) in the brain keep track of the daily cycle. This time-keeping mechanism, called the circadian clock, is found in all animals including us. The circadian clock controls our daily activities such as sleep and wakefulness. Researchers are interested in finding the neuron circuits involved in this time keeping and how the information about daily time in the brain is relayed to the rest of the body. In this image of a brain of the fruit fly Drosophila the time-of-day information flowing through the brain has been visualized by staining the neurons involved: clock neurons (shown in blue) function as "pacemakers" by communicating with neurons that produce a short protein called leucokinin (LK) (red), which, in turn, relays the time signal to other neurons, called LK-R neurons (green). This signaling cascade set in motion by the pacemaker neurons helps synchronize the fly's daily activity with the 24-hour cycle. To learn more about what scientists have found out about circadian pacemaker neurons in the fruit fly see this news release by New York University. This work was featured in the Biomedical Beat blog post Cool Image: A Circadian Circuit.

Justin Blau, New York University

View Media

3489: Worm sperm

3489: Worm sperm

To develop a system for studying cell motility in unnatrual conditions -- a microscope slide instead of the body -- Tom Roberts and Katsuya Shimabukuro at Florida State University disassembled and reconstituted the motility parts used by worm sperm cells.

Tom Roberts, Florida State University

View Media

3251: Spinal nerve cells

3251: Spinal nerve cells

Neurons (green) and glial cells from isolated dorsal root ganglia express COX-2 (red) after exposure to an inflammatory stimulus (cell nuclei are blue). Lawrence Marnett and colleagues have demonstrated that certain drugs selectively block COX-2 metabolism of endocannabinoids -- naturally occurring analgesic molecules -- in stimulated dorsal root ganglia. Featured in the October 20, 2011 issue of Biomedical Beat.

Lawrence Marnett, Vanderbilt University

View Media

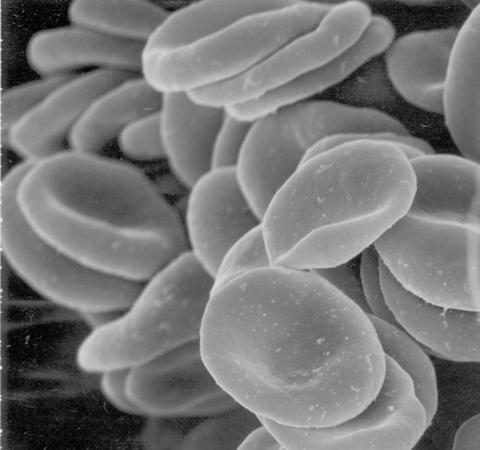

1101: Red blood cells

1101: Red blood cells

This image of human red blood cells was obtained with the help of a scanning electron microscope, an instrument that uses a finely focused electron beam to yield detailed images of the surface of a sample.

Tina Weatherby Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

View Media