Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

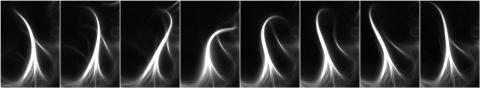

3344: Artificial cilia exhibit spontaneous beating

3344: Artificial cilia exhibit spontaneous beating

Researchers have created artificial cilia that wave like the real thing. Zvonimir Dogic and his Brandeis University colleagues combined just a few cilia proteins to create cilia that are able to wave and sweep material around--although more slowly and simply than real ones. The researchers are using the lab-made cilia to study how the structures coordinate their movements and what happens when they don't move properly. Featured in the August 18, 2011, issue of Biomedical Beat.

Zvonimir Dogic

View Media

2398: RNase A (1)

2398: RNase A (1)

A crystal of RNase A protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

1084: Natcher Building 04

1084: Natcher Building 04

NIGMS staff are located in the Natcher Building on the NIH campus.

Alisa Machalek, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

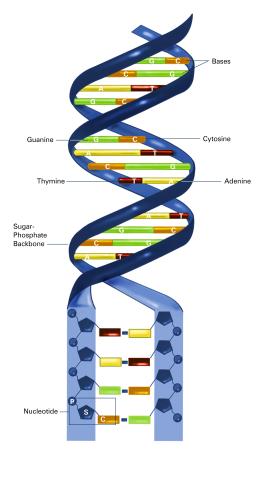

2542: Nucleotides make up DNA (with labels)

2542: Nucleotides make up DNA (with labels)

DNA consists of two long, twisted chains made up of nucleotides. Each nucleotide contains one base, one phosphate molecule, and the sugar molecule deoxyribose. The bases in DNA nucleotides are adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. See image 2541 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

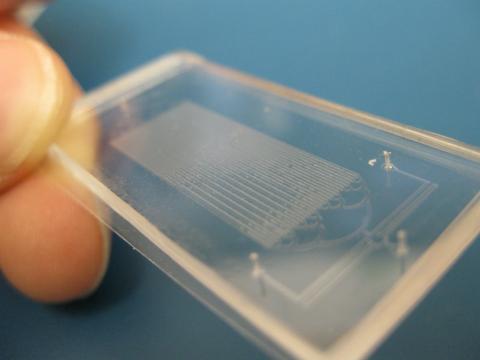

3265: Microfluidic chip

3265: Microfluidic chip

Microfluidic chips have many uses in biology labs. The one shown here was used by bioengineers to study bacteria, allowing the researchers to synchronize their fluorescing so they would blink in unison. Related to images 3266 and 3268. From a UC San Diego news release, "Researchers create living 'neon signs' composed of millions of glowing bacteria."

Jeff Hasty Lab, UC San Diego

View Media

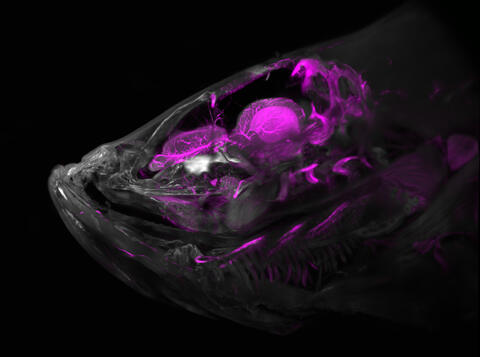

6934: Zebrafish head vasculature

6934: Zebrafish head vasculature

A zebrafish head with blood vessels shown in purple. Researchers often study zebrafish because they share many genes with humans, grow and reproduce quickly, and have see-through eggs and embryos, which make it easy to study early stages of development.

This image was captured using a light sheet microscope.

Related to video 6933.

This image was captured using a light sheet microscope.

Related to video 6933.

Prayag Murawala, MDI Biological Laboratory and Hannover Medical School.

View Media

2423: Protein map

2423: Protein map

Network diagram showing a map of protein-protein interactions in a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cell. This cluster includes 78 percent of the proteins in the yeast proteome. The color of a node represents the phenotypic effect of removing the corresponding protein (red, lethal; green, nonlethal; orange, slow growth; yellow, unknown).

Hawoong Jeong, KAIST, Korea

View Media

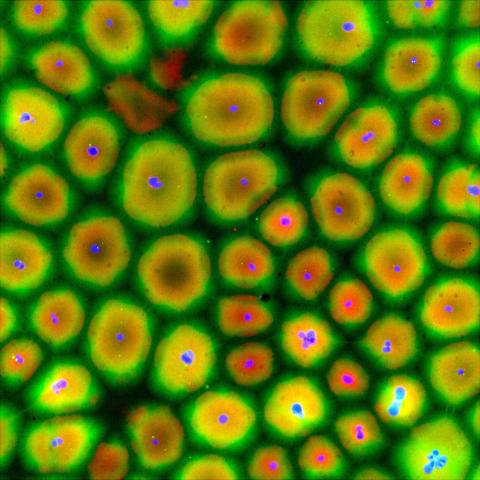

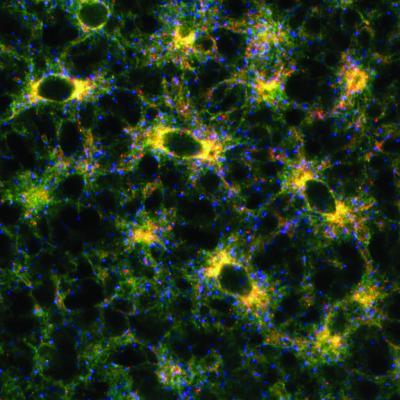

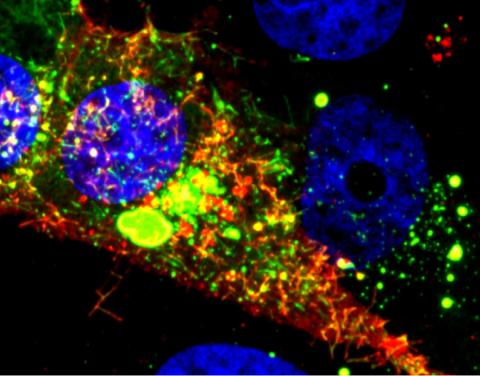

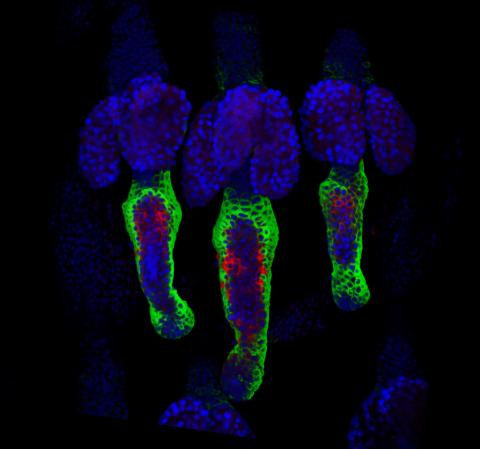

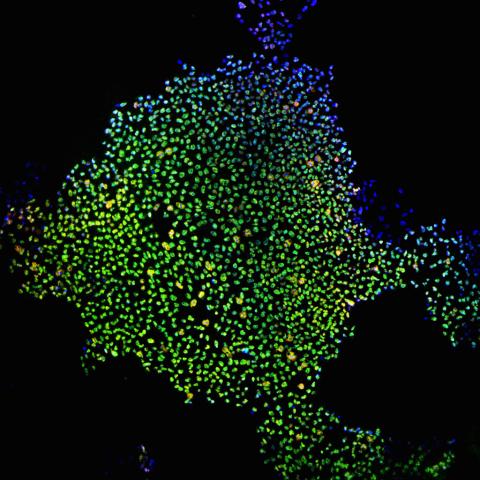

6584: Cell-like compartments from frog eggs

6584: Cell-like compartments from frog eggs

Cell-like compartments that spontaneously emerged from scrambled frog eggs, with nuclei (blue) from frog sperm. Endoplasmic reticulum (red) and microtubules (green) are also visible. Image created using epifluorescence microscopy.

For more photos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6585, 6586, 6591, 6592, and 6593.

For videos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6587, 6588, 6589, and 6590.

Xianrui Cheng, Stanford University School of Medicine.

View Media

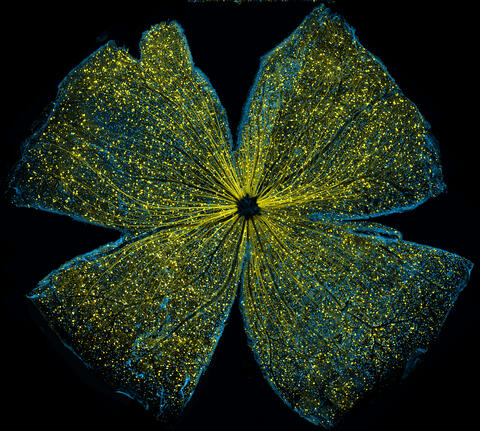

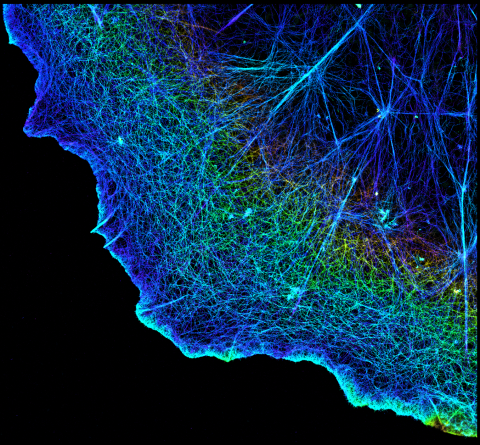

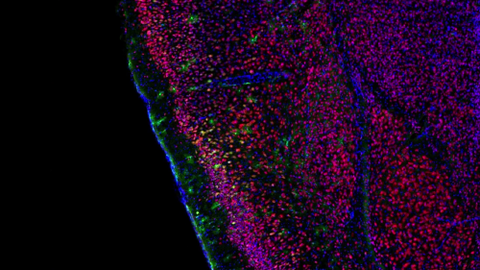

5793: Mouse retina

5793: Mouse retina

What looks like the gossamer wings of a butterfly is actually the retina of a mouse, delicately snipped to lay flat and sparkling with fluorescent molecules. The image is from a research project investigating the promise of gene therapy for glaucoma. It was created at an NIGMS-funded advanced microscopy facility that develops technology for imaging across many scales, from whole organisms to cells to individual molecules.

The ability to obtain high-resolution imaging of tissue as large as whole mouse retinas was made possible by a technique called large-scale mosaic confocal microscopy, which was pioneered by the NIGMS-funded National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research. The technique is similar to Google Earth in that it computationally stitches together many small, high-resolution images.

The ability to obtain high-resolution imaging of tissue as large as whole mouse retinas was made possible by a technique called large-scale mosaic confocal microscopy, which was pioneered by the NIGMS-funded National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research. The technique is similar to Google Earth in that it computationally stitches together many small, high-resolution images.

Tom Deerinck and Keunyoung (“Christine”) Kim, NCMIR

View Media

6850: Himastatin and bacteria

6850: Himastatin and bacteria

A model of the molecule himastatin overlaid on an image of Bacillus subtilis bacteria. Scientists first isolated himastatin from the bacterium Streptomyces himastatinicus, and the molecule shows antibiotic activity. The researchers who created this image developed a new, more concise way to synthesize himastatin so it can be studied more easily. They also tested the effects of himastatin and derivatives of the molecule on B. subtilis.

More information about the research that produced this image can be found in the Science paper “Total synthesis of himastatin” by D’Angelo et al.

Related to image 6848 and video 6851.

More information about the research that produced this image can be found in the Science paper “Total synthesis of himastatin” by D’Angelo et al.

Related to image 6848 and video 6851.

Mohammad Movassaghi, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

View Media

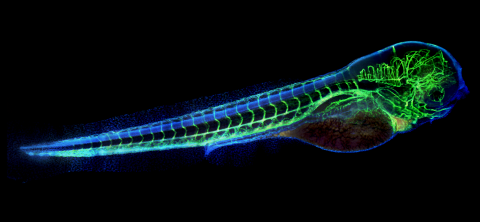

6661: Zebrafish embryo showing vasculature

6661: Zebrafish embryo showing vasculature

A zebrafish embryo. The blue areas are cell bodies, the green lines are blood vessels, and the red glow is blood. This image was created by stitching together five individual images captured with a hyperspectral multipoint confocal fluorescence microscope that was developed at the Eliceiri Lab.

Kevin Eliceiri, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

View Media

3718: A Bacillus subtilis biofilm grown in a Petri dish

3718: A Bacillus subtilis biofilm grown in a Petri dish

Bacterial biofilms are tightly knit communities of bacterial cells growing on, for example, solid surfaces, such as in water pipes or on teeth. Here, cells of the bacterium Bacillus subtilis have formed a biofilm in a laboratory culture. Researchers have discovered that the bacterial cells in a biofilm communicate with each other through electrical signals via specialized potassium ion channels to share resources, such as nutrients, with each other. This insight may help scientists to improve sanitation systems to prevent biofilms, which often resist common treatments, from forming and to develop better medicines to combat bacterial infections. See the Biomedical Beat blog post Bacterial Biofilms: A Charged Environment for more information.

Gürol Süel, UCSD

View Media

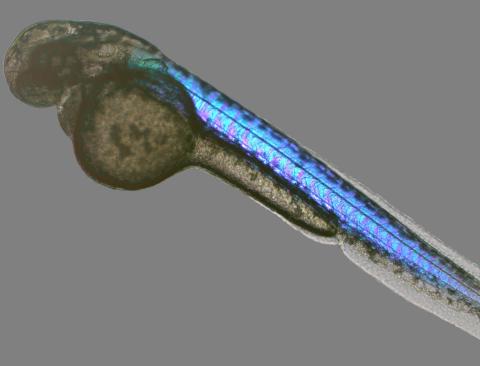

6897: Zebrafish embryo

6897: Zebrafish embryo

A zebrafish embryo showing its natural colors. Zebrafish have see-through eggs and embryos, making them ideal research organisms for studying the earliest stages of development. This image was taken in transmitted light under a polychromatic polarizing microscope.

Michael Shribak, Marine Biological Laboratory/University of Chicago.

View Media

2649: Endoplasmic reticulum

2649: Endoplasmic reticulum

Fluorescent markers show the interconnected web of tubes and compartments in the endoplasmic reticulum. The protein atlastin helps build and maintain this critical part of cells. The image is from a July 2009 news release.

Andrea Daga, Eugenio Medea Scientific Institute (Conegliano, Italy)

View Media

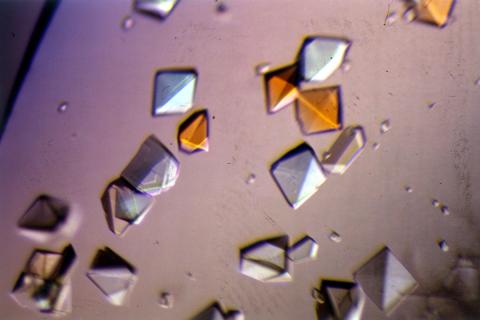

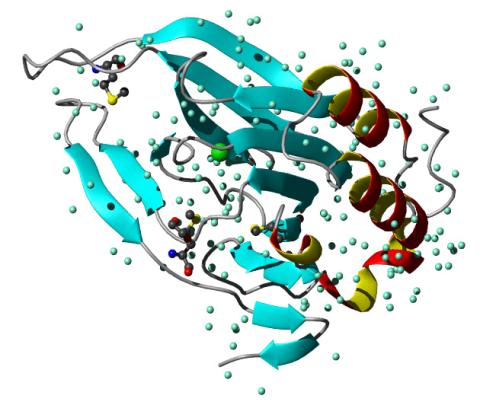

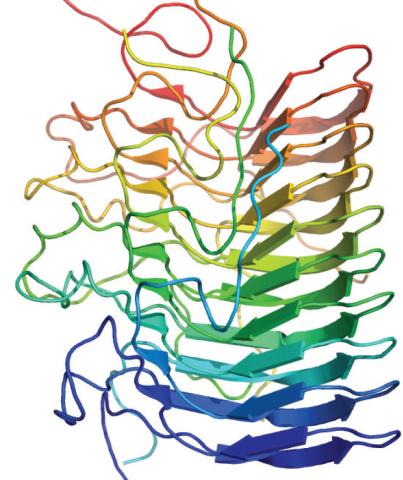

2412: Pig alpha amylase

2412: Pig alpha amylase

Crystals of porcine alpha amylase protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

3549: TonB protein in gram-negative bacteria

3549: TonB protein in gram-negative bacteria

The green in this image highlights a protein called TonB, which is produced by many gram-negative bacteria, including those that cause typhoid fever, meningitis and dysentery. TonB lets bacteria take up iron from the host's body, which they need to survive. More information about the research behind this image can be found in a Biomedical Beat Blog posting from August 2013.

Phillip Klebba, Kansas State University

View Media

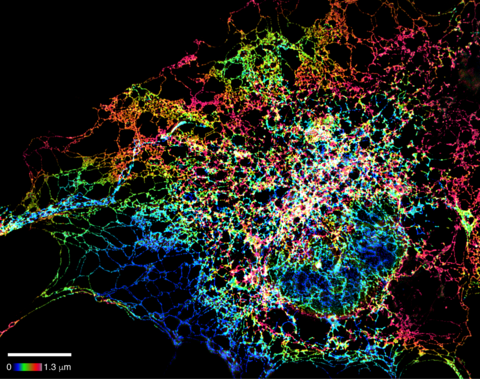

3749: 3D image of actin in a cell

3749: 3D image of actin in a cell

Actin is an essential protein in a cell's skeleton (cytoskeleton). It forms a dense network of thin filaments in the cell. Here, researchers have used a technique called stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) to visualize the actin network in a cell in three dimensions. The actin strands were labeled with a dye called Alexa Fluor 647-phalloidin. This image appears in a study published by Nature Methods, which reports how researchers use STORM to visualize the cytoskeleton.

Xiaowei Zhuang, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Harvard University

View Media

2723: iPS cell facility at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research

2723: iPS cell facility at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research

This lab space was designed for work on the induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell collection, part of the NIGMS Human Genetic Cell Repository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research.

Courtney Sill, Coriell Institute for Medical Research

View Media

6556: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 72 hour

6556: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 72 hour

Floral pattern emerging as two bacterial species, motile Acinetobacter baylyi and non-motile Escherichia coli (green), are grown together for 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface from a small inoculum in the center of a Petri dish.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6553 for a photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6555 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6553 for a photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6555 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

L. Xiong et al, eLife 2020;9: e48885

View Media

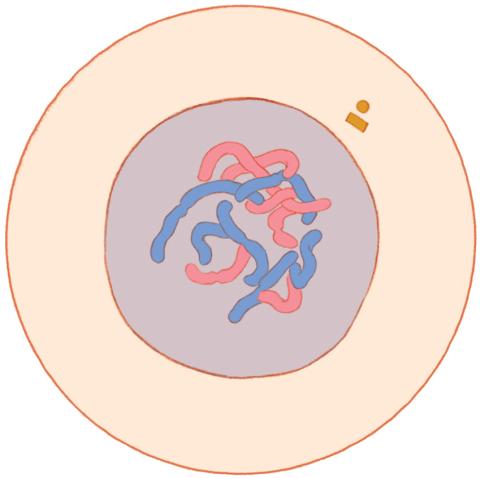

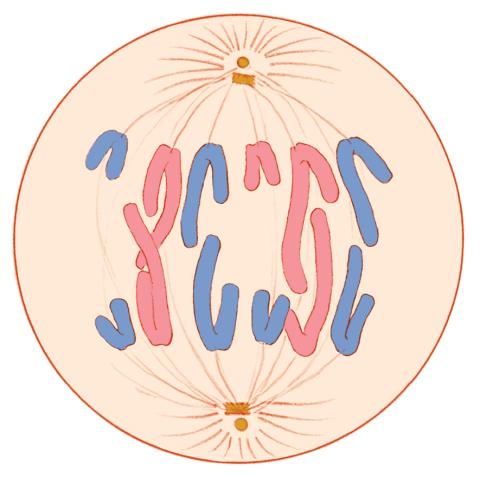

1316: Mitosis - interphase

1316: Mitosis - interphase

A cell in interphase, at the start of mitosis: Chromosomes duplicate, and the copies remain attached to each other. Mitosis is responsible for growth and development, as well as for replacing injured or worn out cells throughout the body. For simplicity, mitosis is illustrated here with only six chromosomes.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

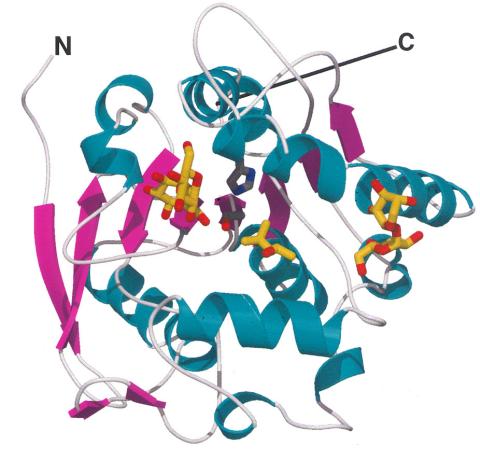

2347: Cysteine dioxygenase from mouse

2347: Cysteine dioxygenase from mouse

Model of the mammalian iron enzyme cysteine dioxygenase from a mouse.

Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics, PSI

View Media

2793: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with hydrogens 04

2793: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with hydrogens 04

Ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743, brand name Yondelis), was discovered and isolated from a sea squirt, Ecteinascidia turbinata, by NIGMS grantee Kenneth Rinehart at the University of Illinois. It was synthesized by NIGMS grantees E.J. Corey and later by Samuel Danishefsky. Multiple versions of this structure are available as entries 2790-2797.

Timothy Jamison, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

View Media

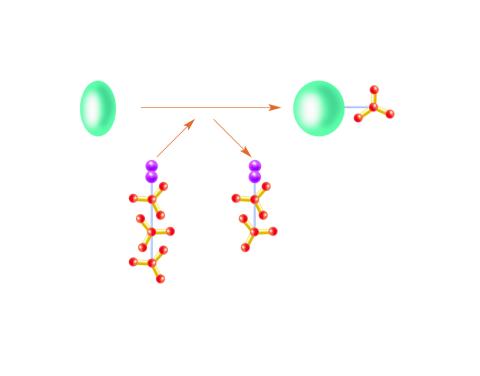

2534: Kinases

2534: Kinases

Kinases are enzymes that add phosphate groups (red-yellow structures) to proteins (green), assigning the proteins a code. In this reaction, an intermediate molecule called ATP (adenosine triphosphate) donates a phosphate group from itself, becoming ADP (adenosine diphosphate). See image 2535 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in Medicines By Design.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

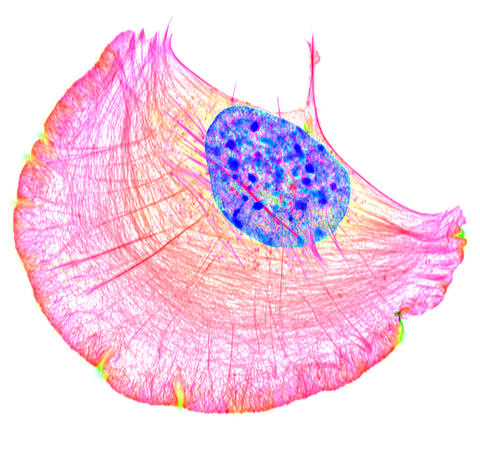

6964: Crawling cell

6964: Crawling cell

A crawling cell with DNA shown in blue and actin filaments, which are a major component of the cytoskeleton, visible in pink. Actin filaments help enable cells to crawl. This image was captured using structured illumination microscopy.

Dylan T. Burnette, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

View Media

6781: Video of Calling Cards in a mouse brain

6781: Video of Calling Cards in a mouse brain

The green spots in this mouse brain are cells labeled with Calling Cards, a technology that records molecular events in brain cells as they mature. Understanding these processes during healthy development can guide further research into what goes wrong in cases of neuropsychiatric disorders. Also fluorescently labeled in this video are neurons (red) and nuclei (blue). Calling Cards and its application are described in the Cell paper “Self-Reporting Transposons Enable Simultaneous Readout of Gene Expression and Transcription Factor Binding in Single Cells” by Moudgil et al.; and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences paper “A viral toolkit for recording transcription factor–DNA interactions in live mouse tissues” by Cammack et al. This video was created for the NIH Director’s Blog post The Amazing Brain: Tracking Molecular Events with Calling Cards.

Related to image 6780.

Related to image 6780.

NIH Director's Blog

View Media

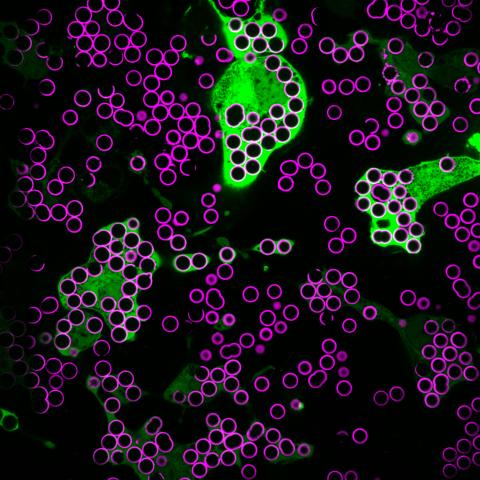

7009: Hungry, hungry macrophages

7009: Hungry, hungry macrophages

Macrophages (green) are the professional eaters of our immune system. They are constantly surveilling our tissues for targets—such as bacteria, dead cells, or even cancer—and clearing them before they can cause harm. In this image, researchers were testing how macrophages responded to different molecules that were attached to silica beads (magenta) coated with a lipid bilayer to mimic a cell membrane.

Find more information on this image in the NIH Director’s Blog post "How to Feed a Macrophage."

Find more information on this image in the NIH Director’s Blog post "How to Feed a Macrophage."

Meghan Morrissey, University of California, Santa Barbara.

View Media

2728: Sponge

2728: Sponge

Many of today's medicines come from products found in nature, such as this sponge found off the coast of Palau in the Pacific Ocean. Chemists have synthesized a compound called Palau'amine, which appears to act against cancer, bacteria and fungi. In doing so, they invented a new chemical technique that will empower the synthesis of other challenging molecules.

Phil Baran, Scripps Research Institute

View Media

6539: Pathways: What is Basic Science?

6539: Pathways: What is Basic Science?

Learn about basic science, sometimes called “pure” or “fundamental” science, and how it contributes to the development of medical treatments. Discover more resources from NIGMS’ Pathways collaboration with Scholastic. View the video on YouTube for closed captioning.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

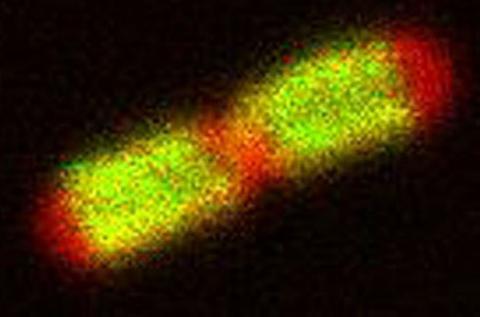

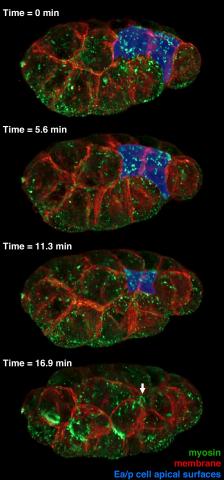

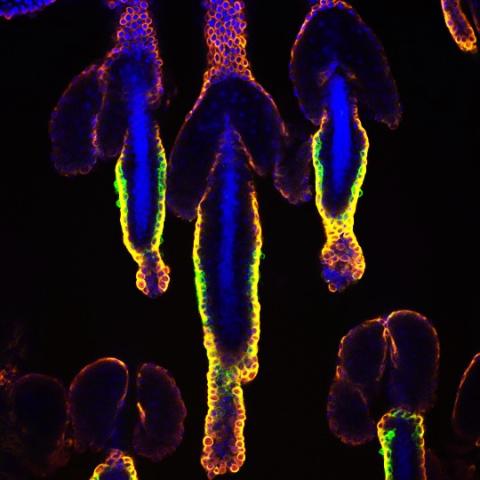

3297: Four timepoints in gastrulation

3297: Four timepoints in gastrulation

It has been said that gastrulation is the most important event in a person's life. This part of early embryonic development transforms a simple ball of cells and begins to define cell fate and the body axis. In a study published in Science magazine in March 2012, NIGMS grantee Bob Goldstein and his research group studied how contractions of actomyosin filaments in C. elegans and Drosophila embryos lead to dramatic rearrangements of cell and embryonic structure. This research is described in detail in the following article: "Triggering a Cell Shape Change by Exploiting Preexisting Actomyosin Contractions." In these images, myosin (green) and plasma membrane (red) are highlighted at four timepoints in gastrulation in the roundworm C. elegans. The blue highlights in the top three frames show how cells are internalized, and the site of closure around the involuting cells is marked with an arrow in the last frame. See related video 3334.

Bob Goldstein, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

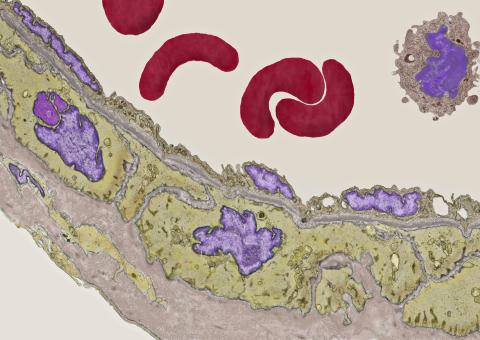

3738: Transmission electron microscopy of coronary artery wall with elastin-rich ECM pseudocolored in light brown

3738: Transmission electron microscopy of coronary artery wall with elastin-rich ECM pseudocolored in light brown

Elastin is a fibrous protein in the extracellular matrix (ECM). It is abundant in artery walls like the one shown here. As its name indicates, elastin confers elasticity. Elastin fibers are at least five times stretchier than rubber bands of the same size. Tissues that expand, such as blood vessels and lungs, need to be both strong and elastic, so they contain both collagen (another ECM protein) and elastin. In this photo, the elastin-rich ECM is colored grayish brown and is most visible at the bottom of the photo. The curved red structures near the top of the image are red blood cells.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

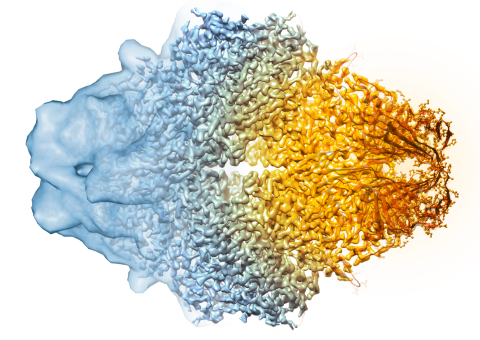

5882: Beta-galactosidase montage showing cryo-EM improvement--transparent background

5882: Beta-galactosidase montage showing cryo-EM improvement--transparent background

Composite image of beta-galactosidase showing how cryo-EM’s resolution has improved dramatically in recent years. Older images to the left, more recent to the right. Related to image 5883. NIH Director Francis Collins featured this on his blog on January 14, 2016.

Veronica Falconieri, Sriram Subramaniam Lab, National Cancer Institute

View Media

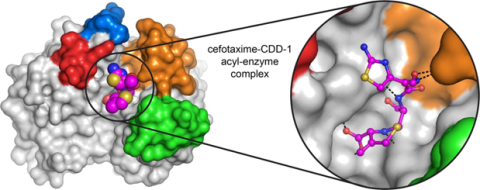

6767: Space-filling model of a cefotaxime-CCD-1 complex

6767: Space-filling model of a cefotaxime-CCD-1 complex

CCD-1 is an enzyme produced by the bacterium Clostridioides difficile that helps it resist antibiotics. Using X-ray crystallography, researchers determined the structure of a complex between CCD-1 and the antibiotic cefotaxime (purple, yellow, and blue molecule). The structure revealed that CCD-1 provides extensive hydrogen bonding (shown as dotted lines) and stabilization of the antibiotic in the active site, leading to efficient degradation of the antibiotic.

Related to images 6764, 6765, and 6766.

Related to images 6764, 6765, and 6766.

Keith Hodgson, Stanford University.

View Media

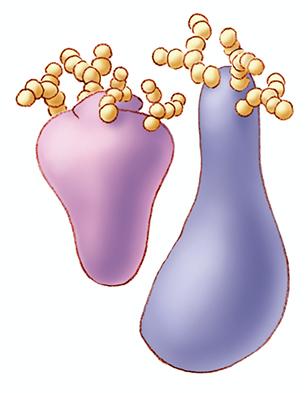

1270: Glycoproteins

1270: Glycoproteins

About half of all human proteins include chains of sugar molecules that are critical for the proteins to function properly. Appears in the NIGMS booklet Inside the Cell.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

3567: RSV-Infected Cell

3567: RSV-Infected Cell

Viral RNA (red) in an RSV-infected cell. More information about the research behind this image can be found in a Biomedical Beat Blog posting from January 2014.

Eric Alonas and Philip Santangelo, Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University

View Media

1083: Natcher Building 03

1083: Natcher Building 03

NIGMS staff are located in the Natcher Building on the NIH campus.

Alisa Machalek, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

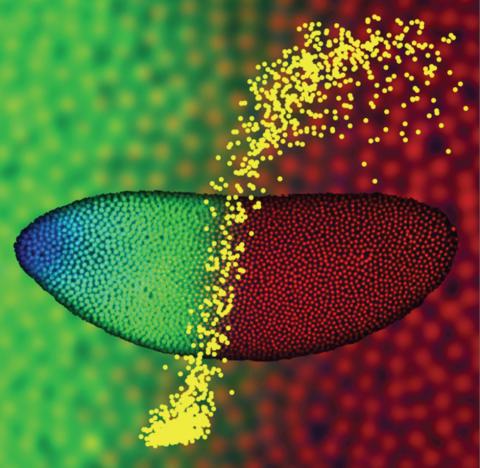

2593: Precise development in the fruit fly embryo

2593: Precise development in the fruit fly embryo

This 2-hour-old fly embryo already has a blueprint for its formation, and the process for following it is so precise that the difference of just a few key molecules can change the plans. Here, blue marks a high concentration of Bicoid, a key signaling protein that directs the formation of the fly's head. It also regulates another important protein, Hunchback (green), that further maps the head and thorax structures and partitions the embryo in half (red is DNA). The yellow dots overlaying the embryo plot the concentration of Bicoid versus Hunchback proteins within each nucleus. The image illustrates the precision with which an embryo interprets and locates its halfway boundary, approaching limits set by simple physical principles. This image was a finalist in the 2008 Drosophila Image Award.

Thomas Gregor, Princeton University

View Media

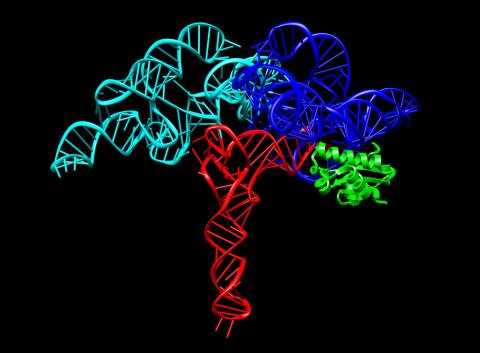

3660: Ribonuclease P structure

3660: Ribonuclease P structure

Ribbon diagram showing the structure of Ribonuclease P with tRNA.

PDB entry 3Q1Q, molecular modeling by Fred Friedman, NIGMS

View Media

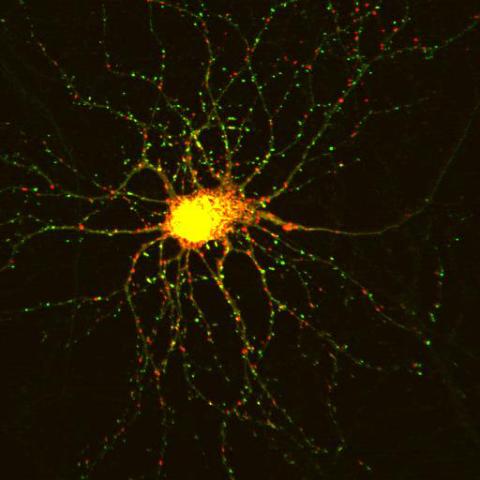

3509: Neuron with labeled synapses

3509: Neuron with labeled synapses

In this image, recombinant probes known as FingRs (Fibronectin Intrabodies Generated by mRNA display) were expressed in a cortical neuron, where they attached fluorescent proteins to either PSD95 (green) or Gephyrin (red). PSD-95 is a marker for synaptic strength at excitatory postsynaptic sites, and Gephyrin plays a similar role at inhibitory postsynaptic sites. Thus, using FingRs it is possible to obtain a map of synaptic connections onto a particular neuron in a living cell in real time.

Don Arnold and Richard Roberts, University of Southern California.

View Media

5855: Dense tubular matrices in the peripheral endoplasmic reticulum (ER) 1

5855: Dense tubular matrices in the peripheral endoplasmic reticulum (ER) 1

Superresolution microscopy work on endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in the peripheral areas of the cell showing details of the structure and arrangement in a complex web of tubes. The ER is a continuous membrane that extends like a net from the envelope of the nucleus outward to the cell membrane. The ER plays several roles within the cell, such as in protein and lipid synthesis and transport of materials between organelles. The ER has a flexible structure to allow it to accomplish these tasks by changing shape as conditions in the cell change. Shown here an image created by super-resolution microscopy of the ER in the peripheral areas of the cell showing details of the structure and the arrangements in a complex web of tubes. Related to images 5856 and 5857.

Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Janelia Research Campus, Virginia

View Media

6553: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 48 hours (photo 1)

6553: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 48 hours (photo 1)

Floral pattern emerging as two bacterial species, motile Acinetobacter baylyi (red) and non-motile Escherichia coli (green), are grown together for 48 hours on 1% agar surface from a small inoculum in the center of a Petri dish.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6555 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6555 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

L. Xiong et al, eLife 2020;9: e48885

View Media

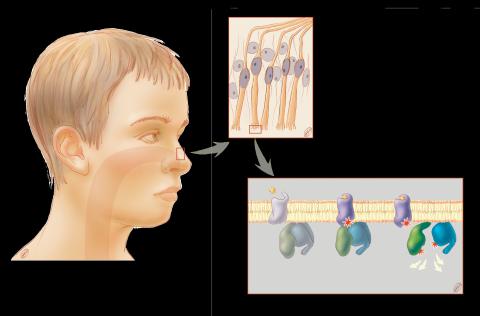

1291: Olfactory system

1291: Olfactory system

Sensory organs have cells equipped for detecting signals from the environment, such as odors. Receptors in the membranes of nerve cells in the nose bind to odor molecules, triggering a cascade of chemical reactions tranferred by G proteins into the cytoplasm.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

2594: Katanin protein regulates anaphase

2594: Katanin protein regulates anaphase

The microtubule severing protein, katanin, localizes to chromosomes and regulates anaphase A in mitosis. The movement of chromosomes on the mitotic spindle requires the depolymerization of microtubule ends. The figure shows the mitotic localization of the microtubule severing protein katanin (green) relative to spindle microtubules (red) and kinetochores/chromosomes (blue). Katanin targets to chromosomes during both metaphase (top) and anaphase (bottom) and is responsible for inducing the depolymerization of attached microtubule plus-ends. This image was a finalist in the 2008 Drosophila Image Award.

David Sharp, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

View Media

2378: Most abundant protein in M. tuberculosis

2378: Most abundant protein in M. tuberculosis

Model of a protein, antigen 85B, that is the most abundant protein exported by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which causes most cases of tuberculosis. Antigen 85B is involved in building the bacterial cell wall and is an attractive drug target. Based on its structure, scientists have suggested a new class of antituberculous drugs.

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Center, PSI

View Media

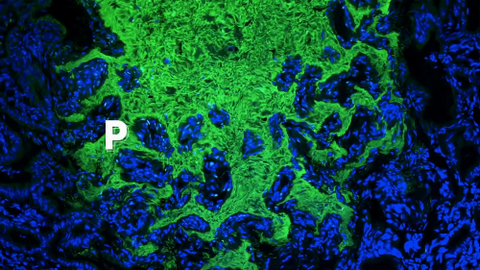

3500: Wound healing in process

3500: Wound healing in process

Wound healing requires the action of stem cells. In mice that lack the Sept2/ARTS gene, stem cells involved in wound healing live longer and wounds heal faster and more thoroughly than in normal mice. This confocal microscopy image from a mouse lacking the Sept2/ARTS gene shows a tail wound in the process of healing. See more information in the article in Science.

Related to images 3497 and 3498.

Related to images 3497 and 3498.

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

3497: Wound healing in process

3497: Wound healing in process

Wound healing requires the action of stem cells. In mice that lack the Sept2/ARTS gene, stem cells involved in wound healing live longer and wounds heal faster and more thoroughly than in normal mice. This confocal microscopy image from a mouse lacking the Sept2/ARTS gene shows a tail wound in the process of healing. See more information in the article in Science.

Related to images 3498 and 3500.

Related to images 3498 and 3500.

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

1328: Mitosis - anaphase

1328: Mitosis - anaphase

A cell in anaphase during mitosis: Chromosomes separate into two genetically identical groups and move to opposite ends of the spindle. Mitosis is responsible for growth and development, as well as for replacing injured or worn out cells throughout the body. For simplicity, mitosis is illustrated here with only six chromosomes.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

3542: Structure of amyloid-forming prion protein

3542: Structure of amyloid-forming prion protein

This structure from an amyloid-forming prion protein shows one way beta sheets can stack. Image originally appeared in a December 2012 PLOS Biology paper.

Douglas Fowler, University of Washington

View Media

2604: Induced stem cells from adult skin 02

2604: Induced stem cells from adult skin 02

These cells are induced stem cells made from human adult skin cells that were genetically reprogrammed to mimic embryonic stem cells. The induced stem cells were made potentially safer by removing the introduced genes and the viral vector used to ferry genes into the cells, a loop of DNA called a plasmid. The work was accomplished by geneticist Junying Yu in the laboratory of James Thomson, a University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health professor and the director of regenerative biology for the Morgridge Institute for Research.

James Thomson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

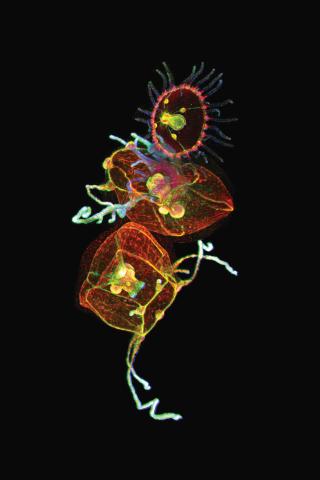

3636: Jellyfish, viewed with ZEISS Lightsheet Z.1 microscope

3636: Jellyfish, viewed with ZEISS Lightsheet Z.1 microscope

Jellyfish are especially good models for studying the evolution of embryonic tissue layers. Despite being primitive, jellyfish have a nervous system (stained green here) and musculature (red). Cell nuclei are stained blue. By studying how tissues are distributed in this simple organism, scientists can learn about the evolution of the shapes and features of diverse animals.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Helena Parra, Pompeu Fabra University, Spain

View Media

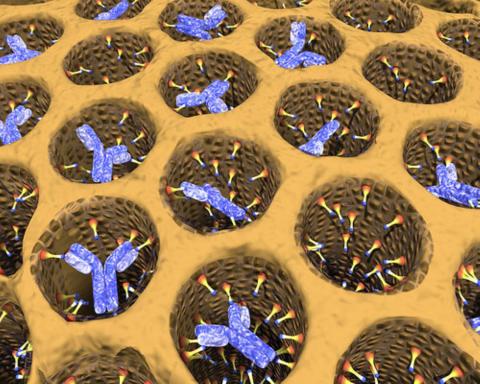

2750: Antibodies in silica honeycomb

2750: Antibodies in silica honeycomb

Antibodies are among the most promising therapies for certain forms of cancer, but patients must take them intravenously, exposing healthy tissues to the drug and increasing the risk of side effects. A team of biochemists packed the anticancer antibodies into porous silica particles to deliver a heavy dose directly to tumors in mice.

Chenghong Lei, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory & Karl Erik Hellstrom, University of Washington

View Media