Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

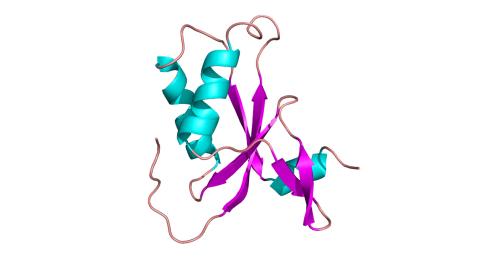

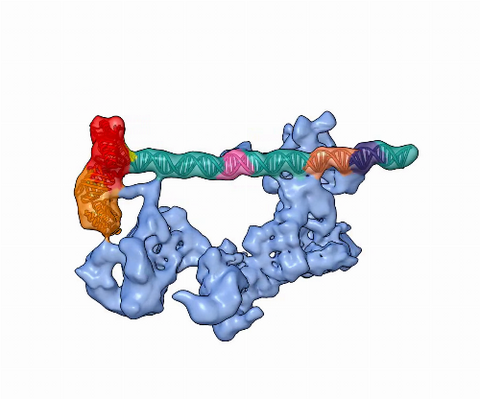

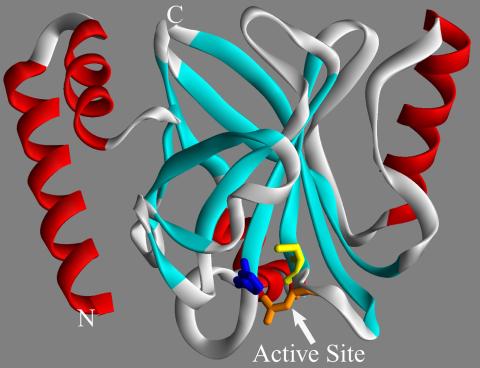

3427: Antitoxin GhoS (Illustration 1)

3427: Antitoxin GhoS (Illustration 1)

Structure of the bacterial antitoxin protein GhoS. GhoS inhibits the production of a bacterial toxin, GhoT, which can contribute to antibiotic resistance. GhoS is the first known bacterial antitoxin that works by cleaving the messenger RNA that carries the instructions for making the toxin. More information can be found in the paper: Wang X, Lord DM, Cheng HY, Osbourne DO, Hong SH, Sanchez-Torres V, Quiroga C, Zheng K, Herrmann T, Peti W, Benedik MJ, Page R, Wood TK. A new type V toxin-antitoxin system where mRNA for toxin GhoT is cleaved by antitoxin GhoS. Nat Chem Biol. 2012 Oct;8(10):855-61. Related to 3428.

Rebecca Page and Wolfgang Peti, Brown University and Thomas K. Wood, Pennsylvania State University

View Media

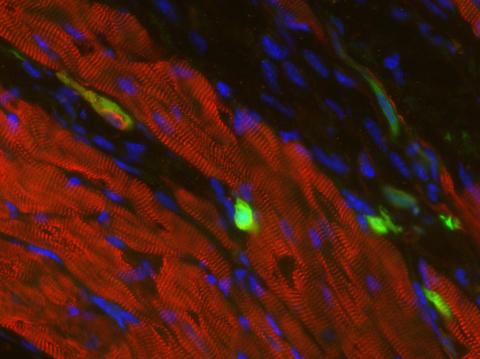

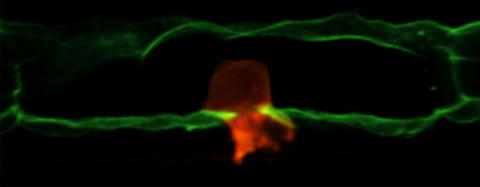

3273: Heart muscle with reprogrammed skin cells

3273: Heart muscle with reprogrammed skin cells

Skins cells were reprogrammed into heart muscle cells. The cells highlighted in green are remaining skin cells. Red indicates a protein that is unique to heart muscle. The technique used to reprogram the skin cells into heart cells could one day be used to mend heart muscle damaged by disease or heart attack. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Deepak Srivastava, Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, via CIRM

View Media

2361: Chromium X-ray source

2361: Chromium X-ray source

In the determination of protein structures by X-ray crystallography, this unique soft (l = 2.29Å) X-ray source is used to collect anomalous scattering data from protein crystals containing light atoms such as sulfur, calcium, zinc and phosphorous. These data can be used to image the protein.

The Southeast Collaboratory for Structural Genomics

View Media

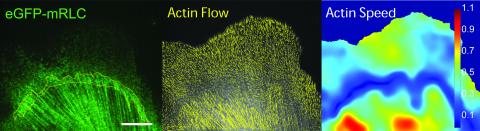

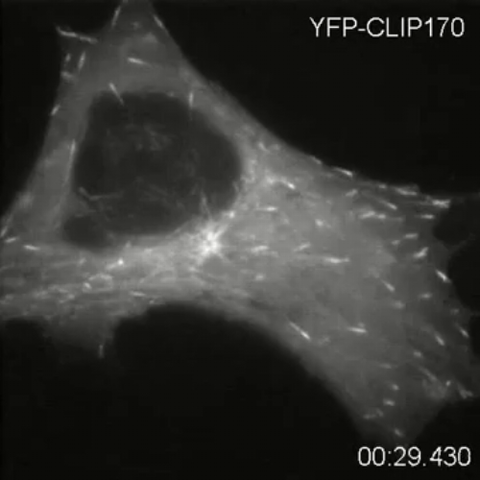

2784: Microtubule dynamics in real time

2784: Microtubule dynamics in real time

Cytoplasmic linker protein (CLIP)-170 is a microtubule plus-end-tracking protein that regulates microtubule dynamics and links microtubule ends to different intracellular structures. In this movie, the gene for CLIP-170 has been fused with green fluorescent protein (GFP). When the protein is expressed in cells, the activities can be monitored in real time. Here, you can see CLIP-170 streaming towards the edges of the cell.

Gary Borisy, Marine Biology Laboratory

View Media

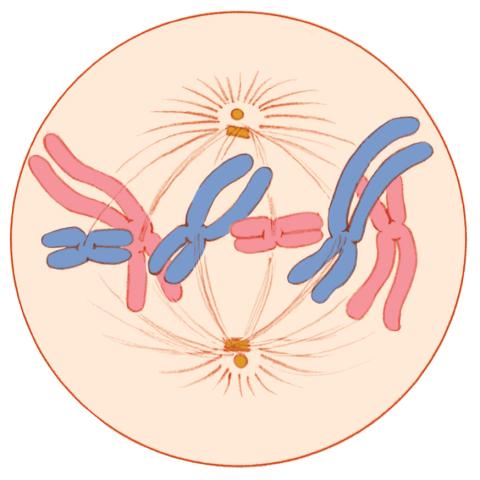

1329: Mitosis - metaphase

1329: Mitosis - metaphase

A cell in metaphase during mitosis: The copied chromosomes align in the middle of the spindle. Mitosis is responsible for growth and development, as well as for replacing injured or worn out cells throughout the body. For simplicity, mitosis is illustrated here with only six chromosomes.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

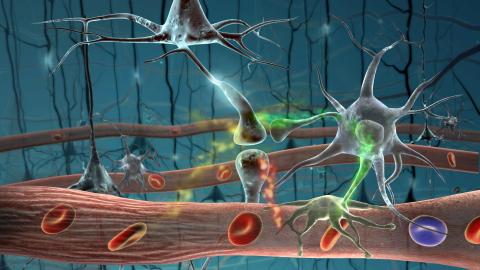

2323: Motion in the brain

2323: Motion in the brain

Amid a network of blood vessels and star-shaped support cells, neurons in the brain signal each other. The mists of color show the flow of important molecules like glucose and oxygen. This image is a snapshot from a 52-second simulation created by an animation artist. Such visualizations make biological processes more accessible and easier to understand.

Kim Hager and Neal Prakash, University of California, Los Angeles

View Media

2709: Retroviruses as fossils

2709: Retroviruses as fossils

DNA doesn't leave a fossil record in stone, the way bones do. Instead, the DNA code itself holds the best evidence for organisms' genetic history. Some of the most telling evidence about genetic history comes from retroviruses, the remnants of ancient viral infections.

Emily Harrington, science illustrator

View Media

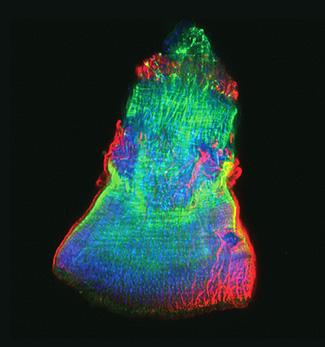

2418: Genetic imprinting in Arabidopsis

2418: Genetic imprinting in Arabidopsis

This delicate, birdlike projection is an immature seed of the Arabidopsis plant. The part in blue shows the cell that gives rise to the endosperm, the tissue that nourishes the embryo. The cell is expressing only the maternal copy of a gene called MEDEA. This phenomenon, in which the activity of a gene can depend on the parent that contributed it, is called genetic imprinting. In Arabidopsis, the maternal copy of MEDEA makes a protein that keeps the paternal copy silent and reduces the size of the endosperm. In flowering plants and mammals, this sort of genetic imprinting is thought to be a way for the mother to protect herself by limiting the resources she gives to any one embryo. Featured in the May 16, 2006, issue of Biomedical Beat.

Robert Fischer, University of California, Berkeley

View Media

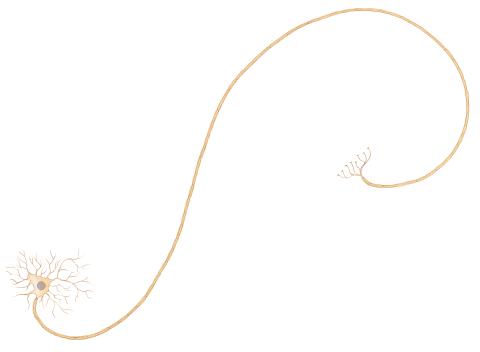

1338: Nerve cell

1338: Nerve cell

Nerve cells have long, invisibly thin fibers that carry electrical impulses throughout the body. Some of these fibers extend about 3 feet from the spinal cord to the toes.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

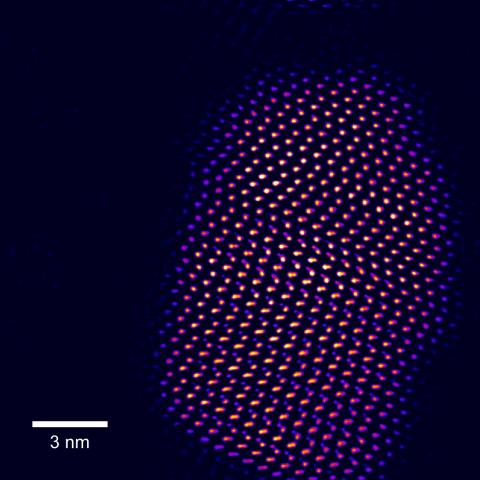

2332: Tiny points of light in a quantum dot

2332: Tiny points of light in a quantum dot

This fingertip-shaped group of lights is a microscopic crystal called a quantum dot. About 10,000 times thinner than a sheet of paper, the dot radiates brilliant colors under ultraviolet light. Dots such as this one allow researchers to label and track individual molecules in living cells and may be used for speedy disease diagnosis, DNA testing, and screening for illegal drugs.

Sandra Rosenthal and James McBride, Vanderbilt University, and Stephen Pennycook, Oak Ridge National Laboratory

View Media

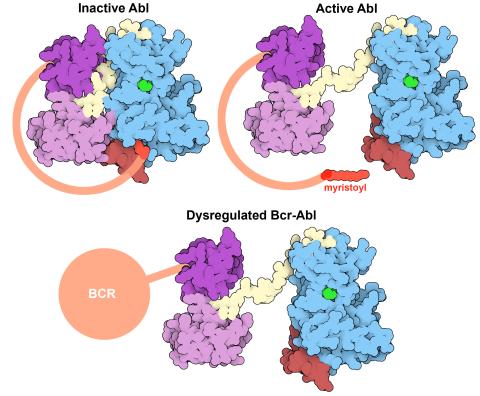

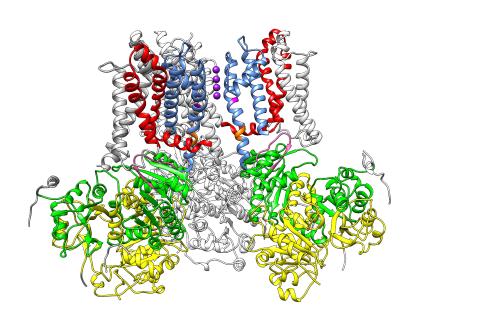

7004: Protein kinases as cancer chemotherapy targets

7004: Protein kinases as cancer chemotherapy targets

Protein kinases—enzymes that add phosphate groups to molecules—are cancer chemotherapy targets because they play significant roles in almost all aspects of cell function, are tightly regulated, and contribute to the development of cancer and other diseases if any alterations to their regulation occur. Genetic abnormalities affecting the c-Abl tyrosine kinase are linked to chronic myelogenous leukemia, a cancer of immature cells in the bone marrow. In the noncancerous form of the protein, binding of a myristoyl group to the kinase domain inhibits the activity of the protein until it is needed (top left shows the inactive form, top right shows the open and active form). The cancerous variant of the protein, called Bcr-Abl, lacks this autoinhibitory myristoyl group and is continually active (bottom). ATP is shown in green bound in the active site of the kinase.

Find these in the RCSB Protein Data Bank: c-Abl tyrosine kinase and regulatory domains (PDB entry 1OPL) and F-actin binding domain (PDB entry 1ZZP).

Find these in the RCSB Protein Data Bank: c-Abl tyrosine kinase and regulatory domains (PDB entry 1OPL) and F-actin binding domain (PDB entry 1ZZP).

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

2637: Activated mast cell surface

2637: Activated mast cell surface

A scanning electron microscope image of an activated mast cell. This image illustrates the interesting topography of the cell membrane, which is populated with receptors. The distribution of receptors may affect cell signaling. This image relates to a July 27, 2009 article in Computing Life.

Bridget Wilson, University of New Mexico

View Media

6522: Fruit fly ovary

6522: Fruit fly ovary

In this image of a stained fruit fly ovary, the ovary is packed with immature eggs (with DNA stained blue). The cytoskeleton (in pink) is a collection of fibers that gives a cell shape and support. The signal-transmitting molecules like STAT (in yellow) are common to reproductive processes in humans. Researchers used this image to show molecular staining and high-resolution imaging techniques to students.

Crystal D. Rogers, Ph.D., University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine; and Mariano A. Loza-Coll, Ph.D., California State University, Northridge.

View Media

2337: Beta2-adrenergic receptor protein

2337: Beta2-adrenergic receptor protein

Crystal structure of the beta2-adrenergic receptor protein. This is the first known structure of a human G protein-coupled receptor, a large family of proteins that control critical bodily functions and the action of about half of today's pharmaceuticals. Featured as one of the November 2007 Protein Structure Initiative Structures of the Month.

The Stevens Laboratory, The Scripps Research Institute

View Media

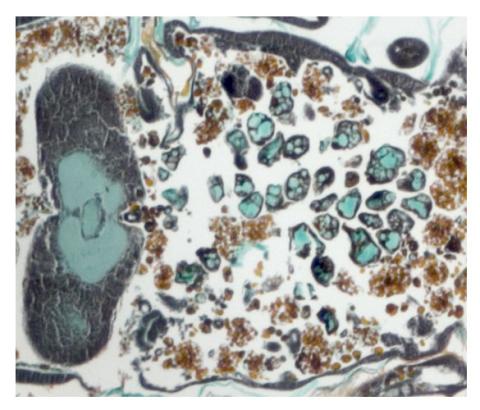

2759: Cross section of a Drosophila melanogaster pupa lacking Draper

2759: Cross section of a Drosophila melanogaster pupa lacking Draper

In the absence of the engulfment receptor Draper, salivary gland cells (light blue) persist in the thorax of a developing Drosophila melanogaster pupa. See image 2758 for a cross section of a normal pupa that does express Draper.

Christina McPhee and Eric Baehrecke, University of Massachusetts Medical School

View Media

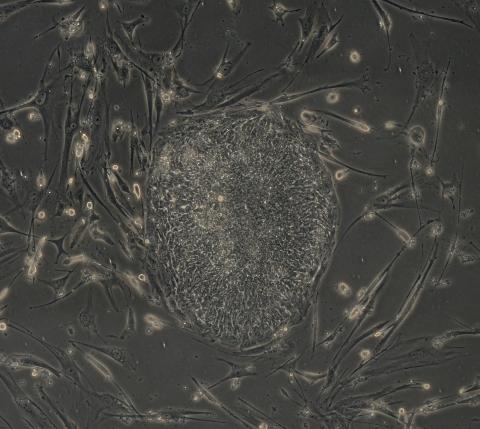

2605: Induced stem cells from adult skin 03

2605: Induced stem cells from adult skin 03

The human skin cells pictured contain genetic modifications that make them pluripotent, essentially equivalent to embryonic stem cells. A scientific team from the University of Wisconsin-Madison including researchers Junying Yu, James Thomson, and their colleagues produced the transformation by introducing a set of four genes into human fibroblasts, skin cells that are easy to obtain and grow in culture.

James Thomson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

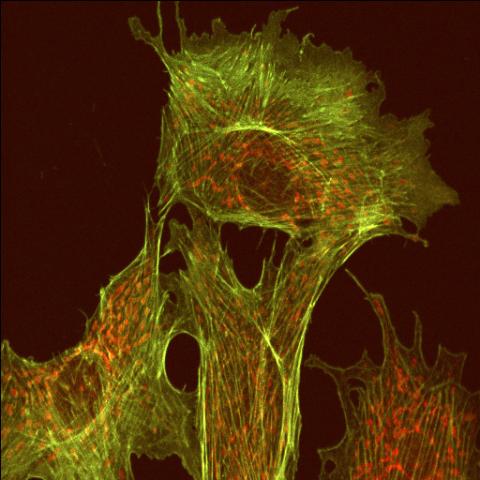

1102: Endothelial cell

1102: Endothelial cell

This image shows two components of the cytoskeleton, microtubules (green) and actin filaments (red), in an endothelial cell derived from a cow lung. The cystoskeleton provides the cell with an inner framework and enables it to move and change shape.

Tina Weatherby Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

View Media

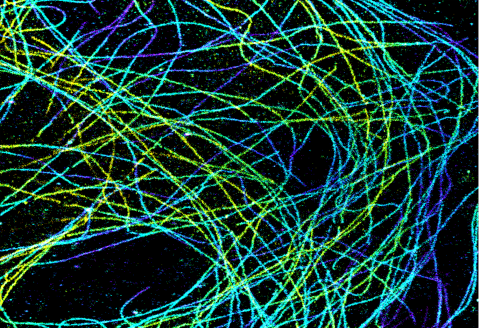

6891: Microtubules in African green monkey cells

6891: Microtubules in African green monkey cells

Microtubules in African green monkey cells. Microtubules are strong, hollow fibers that provide cells with structural support. Here, the microtubules have been color-coded based on their distance from the microscope lens: purple is closest to the lens, and yellow is farthest away. This image was captured using Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy (STORM).

Related to images 6889, 6890, and 6892.

Related to images 6889, 6890, and 6892.

Melike Lakadamyali, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

View Media

2791: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with hydrogens 02

2791: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with hydrogens 02

Ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743, brand name Yondelis), was discovered and isolated from a sea squirt, Ecteinascidia turbinata, by NIGMS grantee Kenneth Rinehart at the University of Illinois. It was synthesized by NIGMS grantees E.J. Corey and later by Samuel Danishefsky. Multiple versions of this structure are available as entries 2790-2797.

Timothy Jamison, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

View Media

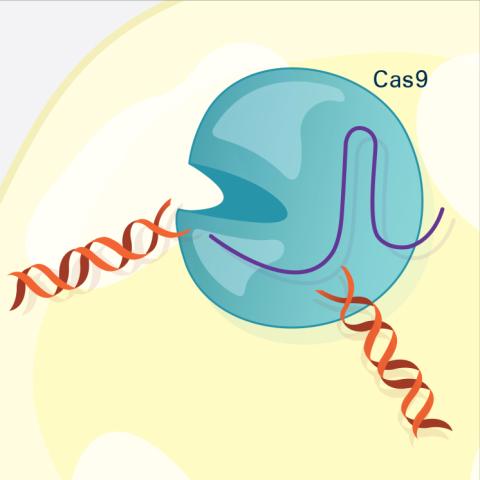

6487: CRISPR Illustration Frame 3

6487: CRISPR Illustration Frame 3

This illustration shows, in simplified terms, how the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used as a gene-editing tool. The CRISPR system has two components joined together: a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence) and a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA). In this frame (3 of 4), the Cas9 enzyme cuts both strands of the DNA.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and find the full CRIPSR illustration here.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and find the full CRIPSR illustration here.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

View Media

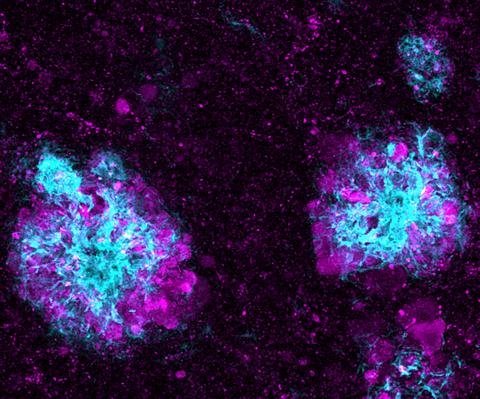

5771: Lysosome clusters around amyloid plaques

5771: Lysosome clusters around amyloid plaques

It's probably most people's least favorite activity, but we still need to do it--take out our trash. Otherwise our homes will get cluttered and smelly, and eventually, we'll get sick. The same is true for our cells: garbage disposal is an ongoing and essential activity, and our cells have a dedicated waste-management system that helps keep them clean and neat. One major waste-removal agent in the cell is the lysosome. Lysosomes are small structures, called organelles, and help the body to dispose of proteins and other molecules that have become damaged or worn out.

This image shows a massive accumulation of lysosomes (visualized with LAMP1 immunofluorescence, in purple) within nerve cells that surround amyloid plaques (visualized with beta-amyloid immunofluorescence, in light blue) in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Scientists have linked accumulation of lysosomes around amyloid plaques to impaired waste disposal in nerve cells, ultimately resulting in cell death.

This image shows a massive accumulation of lysosomes (visualized with LAMP1 immunofluorescence, in purple) within nerve cells that surround amyloid plaques (visualized with beta-amyloid immunofluorescence, in light blue) in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Scientists have linked accumulation of lysosomes around amyloid plaques to impaired waste disposal in nerve cells, ultimately resulting in cell death.

Swetha Gowrishankar and Shawn Ferguson, Yale School of Medicine

View Media

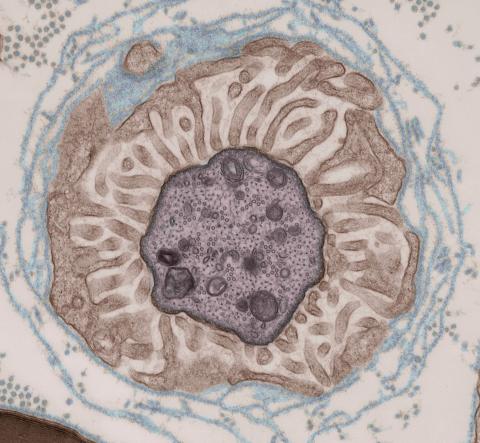

5730: Dynamic cryo-EM model of the human transcription preinitiation complex

5730: Dynamic cryo-EM model of the human transcription preinitiation complex

Gene transcription is a process by which information encoded in DNA is transcribed into RNA. It's essential for all life and requires the activity of proteins, called transcription factors, that detect where in a DNA strand transcription should start. In eukaryotes (i.e., those that have a nucleus and mitochondria), a protein complex comprising 14 different proteins is responsible for sniffing out transcription start sites and starting the process. This complex represents the core machinery to which an enzyme, named RNA polymerase, can bind to and read the DNA and transcribe it to RNA. Scientists have used cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to visualize the TFIID-RNA polymerase-DNA complex in unprecedented detail. This animation shows the different TFIID components as they contact DNA and recruit the RNA polymerase for gene transcription.

To learn more about the research that has shed new light on gene transcription, see this news release from Berkeley Lab.

Related to image 3766.

To learn more about the research that has shed new light on gene transcription, see this news release from Berkeley Lab.

Related to image 3766.

Eva Nogales, Berkeley Lab

View Media

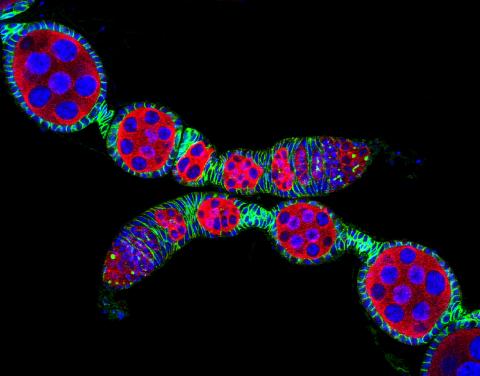

5772: Confocal microscopy image of two Drosophila ovarioles

5772: Confocal microscopy image of two Drosophila ovarioles

Ovarioles in female insects are tubes in which egg cells (called oocytes) form at one end and complete their development as they reach the other end of the tube. This image, taken with a confocal microscope, shows ovarioles in a very popular lab animal, the fruit fly Drosophila. The basic structure of ovarioles supports very rapid egg production, with some insects (like termites) producing several thousand eggs per day. Each insect ovary typically contains four to eight ovarioles, but this number varies widely depending on the insect species.

Scientists use insect ovarioles, for example, to study the basic processes that help various insects, including those that cause disease (like some mosquitos and biting flies), reproduce very quickly.

Scientists use insect ovarioles, for example, to study the basic processes that help various insects, including those that cause disease (like some mosquitos and biting flies), reproduce very quickly.

2004 Olympus BioScapes Competition

View Media

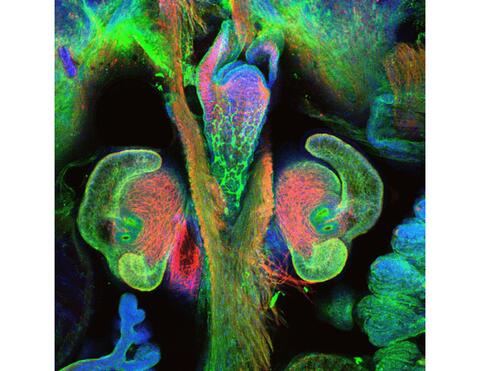

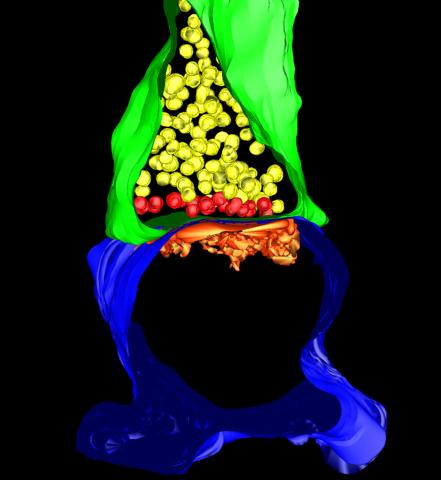

7017: The nascent juvenile light organ of the Hawaiian bobtail squid

7017: The nascent juvenile light organ of the Hawaiian bobtail squid

A light organ (~0.5 mm across) of a Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes, with different tissues are stained various colors. The two pairs of ciliated appendages, or “arms,” on the sides of the organ move Vibrio fischeri bacterial cells closer to the two sets of three pores (two seen in this image) at the base of the arms that each lead to an interior crypt. This image was taken using a confocal fluorescence microscope.

Related to images 7016, 7018, 7019, and 7020.

Related to images 7016, 7018, 7019, and 7020.

Margaret J. McFall-Ngai, Carnegie Institution for Science/California Institute of Technology, and Edward G. Ruby, California Institute of Technology.

View Media

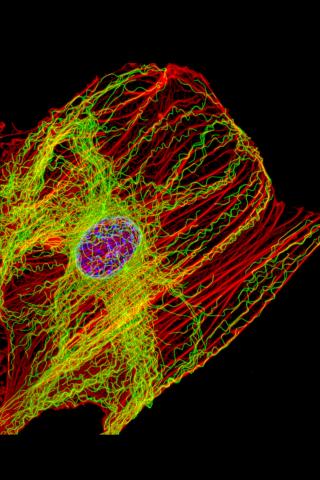

3617: Cells keep their shape with actin filaments and microtubules

3617: Cells keep their shape with actin filaments and microtubules

This image shows a normal fibroblast, a type of cell that is common in connective tissue and frequently studied in research labs. This cell has a healthy skeleton composed of actin (red) and microtubles (green). Actin fibers act like muscles to create tension and microtubules act like bones to withstand compression.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

James J. Faust and David G. Capco, Arizona State University

View Media

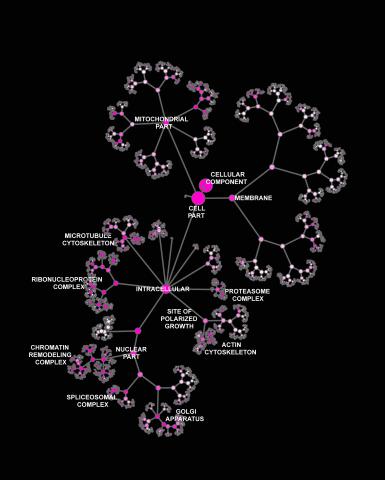

3437: Network diagram of genes, cellular components and processes (labeled)

3437: Network diagram of genes, cellular components and processes (labeled)

This image shows the hierarchical ontology of genes, cellular components and processes derived from large genomic datasets. From Dutkowski et al. A gene ontology inferred from molecular networks Nat Biotechnol. 2013 Jan;31(1):38-45. Related to 3436.

Janusz Dutkowski and Trey Ideker, University of California, San Diego

View Media

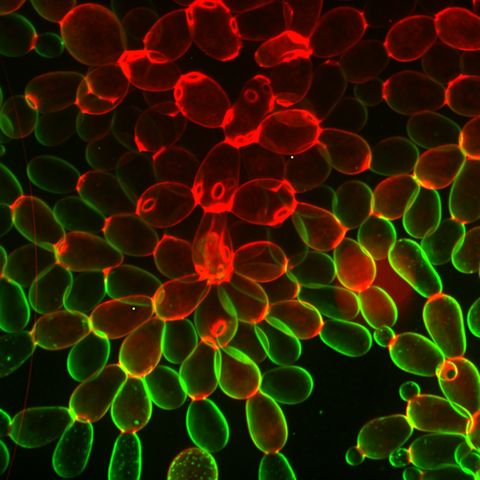

6969: Snowflake yeast 1

6969: Snowflake yeast 1

Multicellular yeast called snowflake yeast that researchers created through many generations of directed evolution from unicellular yeast. Stained cell membranes (green) and cell walls (red) reveal the connections between cells. Younger cells take up more cell membrane stain, while older cells take up more cell wall stain, leading to the color differences seen here. This image was captured using spinning disk confocal microscopy.

Related to images 6970 and 6971.

Related to images 6970 and 6971.

William Ratcliff, Georgia Institute of Technology.

View Media

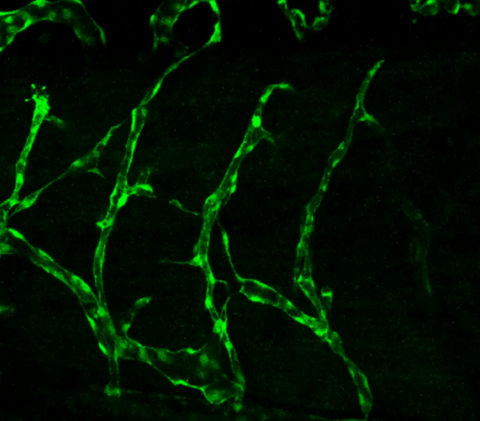

3403: Disrupted vascular development in frog embryos

3403: Disrupted vascular development in frog embryos

Disassembly of vasculature in kdr:GFP frogs following addition of 250 µM TBZ. Related to images 3404 and 3505.

Hye Ji Cha, University of Texas at Austin

View Media

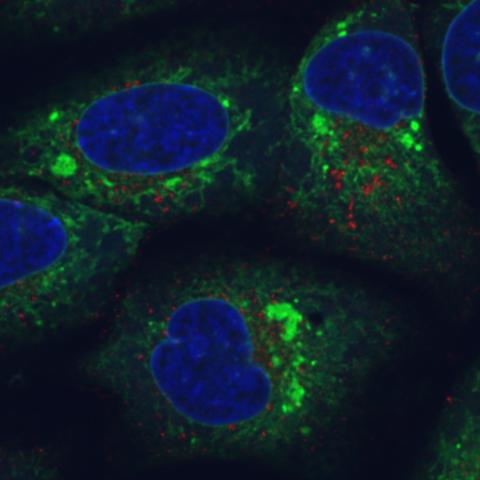

6773: Endoplasmic reticulum abnormalities

6773: Endoplasmic reticulum abnormalities

Human cells with the gene that codes for the protein FIT2 deleted. Green indicates an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resident protein. The lack of FIT2 affected the structure of the ER and caused the resident protein to cluster in ER membrane aggregates, seen as large, bright-green spots. Red shows where the degradation of cell parts—called autophagy—is taking place, and the nucleus is visible in blue. This image was captured using a confocal microscope.

Michel Becuwe, Harvard University.

View Media

2386: Sortase b from B. anthracis

2386: Sortase b from B. anthracis

Structure of sortase b from the bacterium B. anthracis, which causes anthrax. Sortase b is an enzyme used to rob red blood cells of iron, which the bacteria need to survive.

Midwest Center for Structural Genomics, PSI

View Media

5759: TEM cross-section of C. elegans (roundworm)

5759: TEM cross-section of C. elegans (roundworm)

The worm Caenorhabditis elegans is a popular laboratory animal because its small size and fairly simple body make it easy to study. Scientists use this small worm to answer many research questions in developmental biology, neurobiology, and genetics. This image, which was taken with transmission electron microscopy (TEM), shows a cross-section through C. elegans, revealing various internal structures.

The image is from a figure in an article published in the journal eLife. There is an annotated version of this graphic at 5760.

The image is from a figure in an article published in the journal eLife. There is an annotated version of this graphic at 5760.

Piali Sengupta, Brandeis University

View Media

3740: Transmission electron microscopy showing cross-section of the node of Ranvier

3740: Transmission electron microscopy showing cross-section of the node of Ranvier

Nodes of Ranvier are short gaps in the myelin sheath surrounding myelinated nerve cells (axons). Myelin insulates axons, and the node of Ranvier is where the axon is exposed to the extracellular environment, allowing for the transmission of action potentials at these nodes via ion flows between the inside and outside of the axon. The image shows a cross-section through the node, with the surrounding extracellular matrix encasing and supporting the axon shown in cyan.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

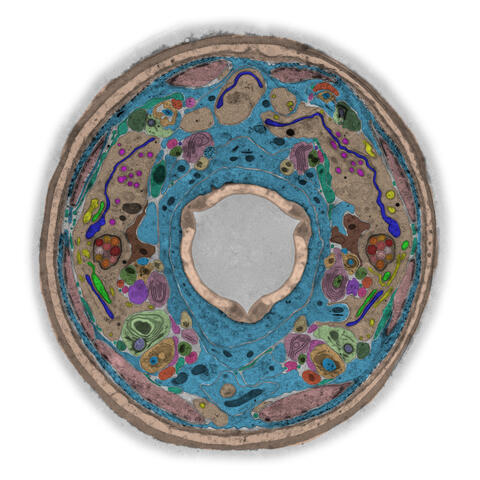

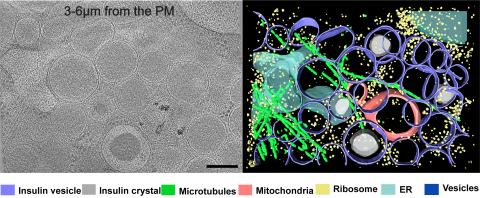

6607: Cryo-ET cell cross-section visualizing insulin vesicles

6607: Cryo-ET cell cross-section visualizing insulin vesicles

On the left, a cross-section slice of a rat pancreas cell captured using cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET). On the right, a color-coded, 3D version of the image highlighting cell structures. Visible features include insulin vesicles (purple rings), insulin crystals (gray circles), microtubules (green rods), ribosomes (small yellow circles). The black line at the bottom right of the left image represents 200 nm. Related to image 6608.

Xianjun Zhang, University of Southern California.

View Media

5885: 3-D Architecture of a Synapse

5885: 3-D Architecture of a Synapse

This image shows the structure of a synapse, or junction between two nerve cells in three dimensions. From the brain of a mouse.

Anton Maximov, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA

View Media

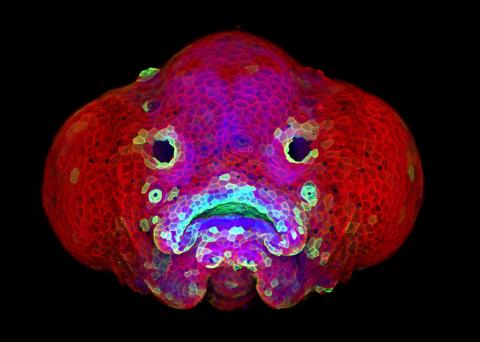

5881: Zebrafish larva

5881: Zebrafish larva

You are face to face with a 6-day-old zebrafish larva. What look like eyes will become nostrils, and the bulges on either side will become eyes. Scientists use fast-growing, transparent zebrafish to see body shapes form and organs develop over the course of just a few days. Images like this one help researchers understand how gene mutations can lead to facial abnormalities such as cleft lip and palate in people.

This image won a 2016 FASEB BioArt award. In addition, NIH Director Francis Collins featured this on his blog on January 26, 2017.

This image won a 2016 FASEB BioArt award. In addition, NIH Director Francis Collins featured this on his blog on January 26, 2017.

Oscar Ruiz and George Eisenhoffer, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

View Media

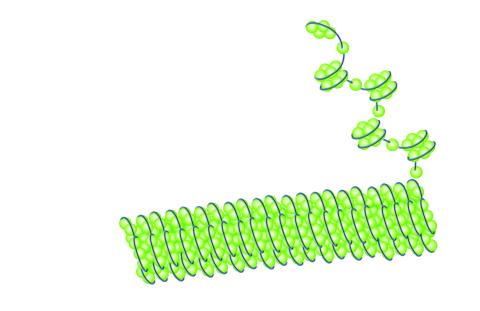

2560: Histones in chromatin

2560: Histones in chromatin

Histone proteins loop together with double-stranded DNA to form a structure that resembles beads on a string. See image 2561 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

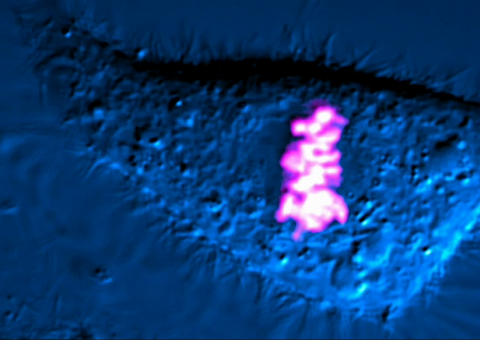

6965: Dividing cell

6965: Dividing cell

As this cell was undergoing cell division, it was imaged with two microscopy techniques: differential interference contrast (DIC) and confocal. The DIC view appears in blue and shows the entire cell. The confocal view appears in pink and shows the chromosomes.

Dylan T. Burnette, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

View Media

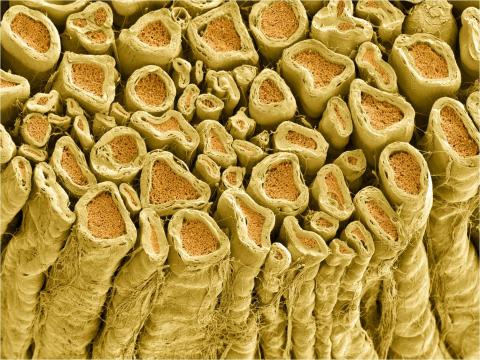

3396: Myelinated axons 1

3396: Myelinated axons 1

Myelinated axons in a rat spinal root. Myelin is a type of fat that forms a sheath around and thus insulates the axon to protect it from losing the electrical current needed to transmit signals along the axon. The axoplasm inside the axon is shown in pink. Related to 3397.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

3593: Isolated Planarian Pharynx

3593: Isolated Planarian Pharynx

The feeding tube, or pharynx, of a planarian worm with cilia shown in red and muscle fibers shown in green

View Media

1293: Sperm cell

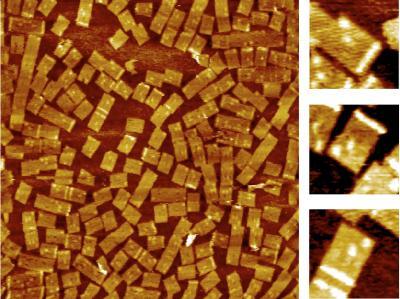

2455: Golden gene chips

2455: Golden gene chips

A team of chemists and physicists used nanotechnology and DNA's ability to self-assemble with matching RNA to create a new kind of chip for measuring gene activity. When RNA of a gene of interest binds to a DNA tile (gold squares), it creates a raised surface (white areas) that can be detected by a powerful microscope. This nanochip approach offers manufacturing and usage advantages over existing gene chips and is a key step toward detecting gene activity in a single cell. Featured in the February 20, 2008, issue of Biomedical Beat.

Hao Yan and Yonggang Ke, Arizona State University

View Media

2707: Anchor cell in basement membrane

2707: Anchor cell in basement membrane

An anchor cell (red) pushes through the basement membrane (green) that surrounds it. Some cells are able to push through the tough basement barrier to carry out important tasks--and so can cancer cells, when they spread from one part of the body to another. No one has been able to recreate basement membranes in the lab and they're hard to study in humans, so Duke University researchers turned to the simple worm C. elegans. The researchers identified two molecules that help certain cells orient themselves toward and then punch through the worm's basement membrane. Studying these molecules and the genes that control them could deepen our understanding of cancer spread.

Elliott Hagedorn, Duke University.

View Media

3487: Ion channel

3487: Ion channel

A special "messy" region of a potassium ion channel is important in its function.

Yu Zhoi, Christopher Lingle Laboratory, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

View Media

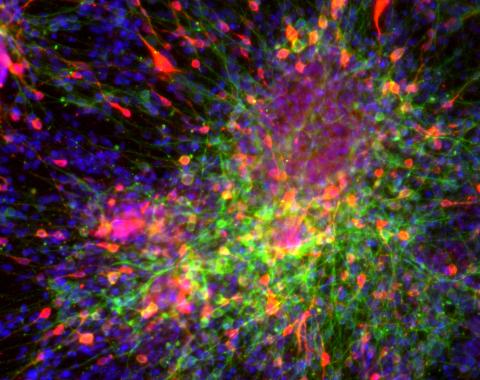

3271: Dopaminergic neurons derived from mouse embryonic stem cells

3271: Dopaminergic neurons derived from mouse embryonic stem cells

These neurons are derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. Red shows cells making a protein called TH that is characteristic of the neurons that degenerate in Parkinson's disease. Green indicates a protein that's found in all neurons. Blue indicates the nuclei of all cells. Studying dopaminergic neurons can help researchers understand the origins of Parkinson's disease and could be used to screen potential new drugs. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Related to images 3270 and 3285.

Yaping Sun, lab of Su Guo, University of California, San Francisco, via CIRM

View Media

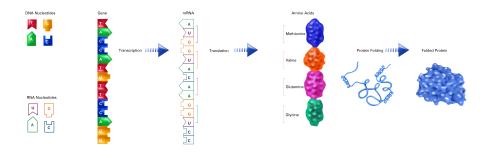

2510: From DNA to Protein (labeled)

2510: From DNA to Protein (labeled)

The genetic code in DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is translated into proteins with specific sequences. During transcription, nucleotides in DNA are copied into RNA, where they are read three at a time to encode the amino acids in a protein. Many parts of a protein fold as the amino acids are strung together.

See image 2509 for an unlabeled version of this illustration.

Featured in The Structures of Life.

See image 2509 for an unlabeled version of this illustration.

Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2369: Protein purification robot in action 01

2369: Protein purification robot in action 01

A robot is transferring 96 purification columns to a vacuum manifold for subsequent purification procedures.

The Northeast Collaboratory for Structural Genomics

View Media

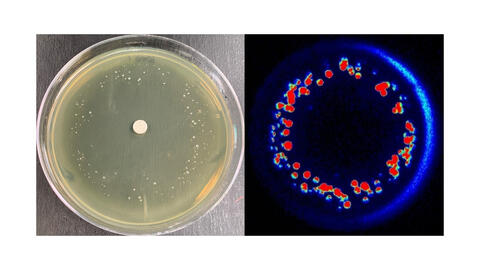

6802: Antibiotic-surviving bacteria

6802: Antibiotic-surviving bacteria

Colonies of bacteria growing despite high concentrations of antibiotics. These colonies are visible both by eye, as seen on the left, and by bioluminescence imaging, as seen on the right. The bioluminescent color indicates the metabolic activity of these bacteria, with their red centers indicating high metabolism.

More information about the research that produced this image can be found in the Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy paper “Novel aminoglycoside-tolerant phoenix colony variants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa” by Sindeldecker et al.

More information about the research that produced this image can be found in the Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy paper “Novel aminoglycoside-tolerant phoenix colony variants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa” by Sindeldecker et al.

Paul Stoodley, The Ohio State University.

View Media

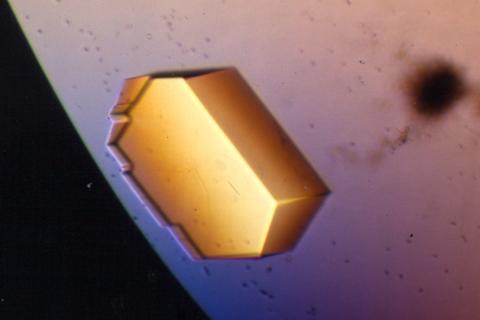

2413: Pig trypsin (2)

2413: Pig trypsin (2)

A crystal of porcine trypsin protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

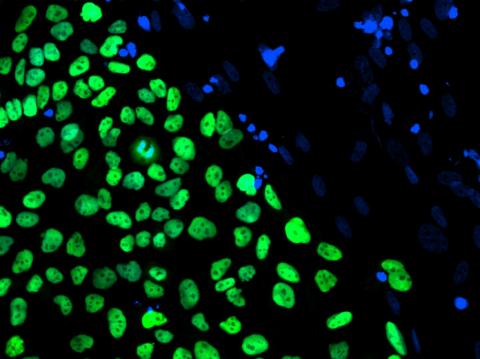

3275: Human embryonic stem cells on feeder cells

3275: Human embryonic stem cells on feeder cells

The nuclei stained green highlight human embryonic stem cells grown under controlled conditions in a laboratory. Blue represents the DNA of surrounding, supportive feeder cells. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. See related image 3724.

Julie Baker lab, Stanford University School of Medicine, via CIRM

View Media