Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

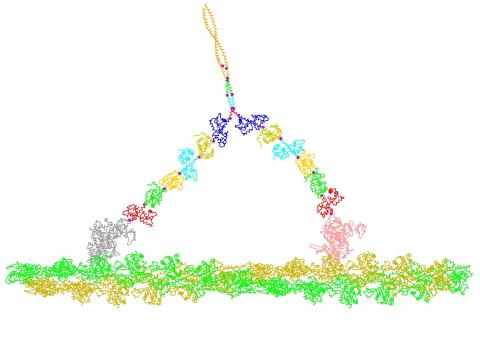

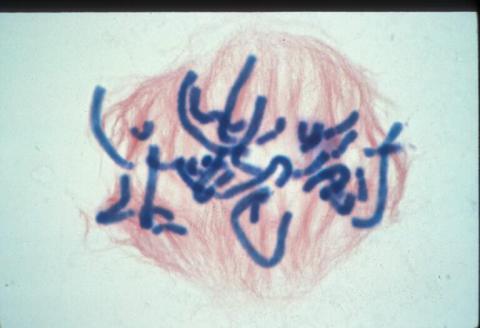

6555: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 48 hours (photo 2)

6555: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 48 hours (photo 2)

Floral pattern emerging as two bacterial species, motile Acinetobacter baylyi (red) and non-motile Escherichia coli (green), are grown together for 48 hours on 1% agar surface from a small inoculum in the center of a Petri dish.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6553 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6553 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

L. Xiong et al, eLife 2020;9: e48885

View Media

6548: Partial Model of a Cilium’s Doublet Microtubule

6548: Partial Model of a Cilium’s Doublet Microtubule

Cilia (cilium in singular) are complex molecular machines found on many of our cells. One component of cilia is the doublet microtubule, a major part of cilia’s skeletons that give them support and shape. This animated image is a partial model of a doublet microtubule’s structure based on cryo-electron microscopy images. Video can be found here 6549.

Brown Lab, Harvard Medical School and Veronica Falconieri Hays.

View Media

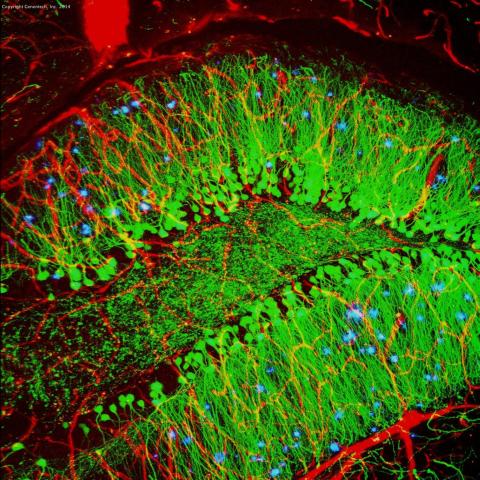

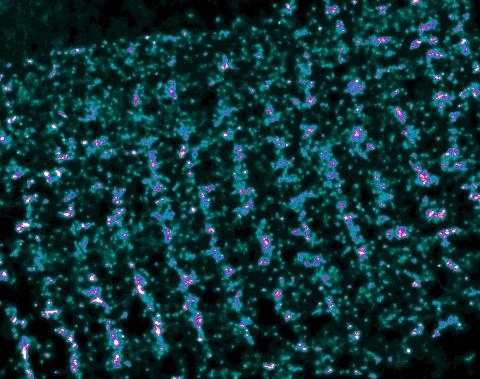

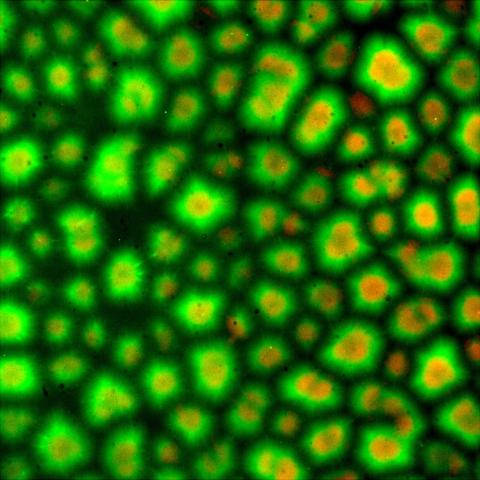

3604: Brain showing hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease

3604: Brain showing hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease

Along with blood vessels (red) and nerve cells (green), this mouse brain shows abnormal protein clumps known as plaques (blue). These plaques multiply in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease and are associated with the memory impairment characteristic of the disease. Because mice have genomes nearly identical to our own, they are used to study both the genetic and environmental factors that trigger Alzheimer's disease. Experimental treatments are also tested in mice to identify the best potential therapies for human patients.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Alvin Gogineni, Genentech

View Media

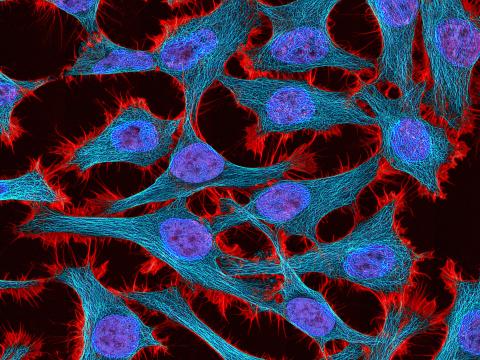

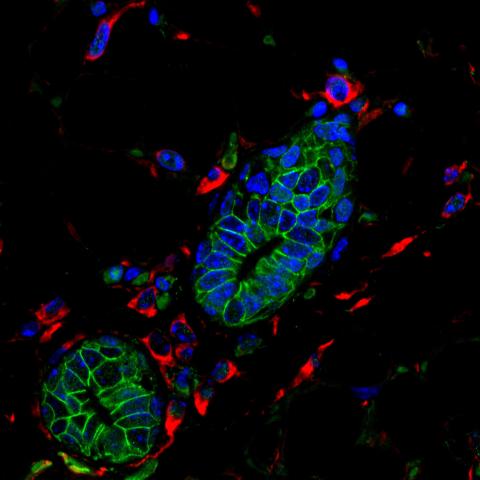

3521: HeLa cells

3521: HeLa cells

Multiphoton fluorescence image of HeLa cells stained with the actin binding toxin phalloidin (red), microtubules (cyan) and cell nuclei (blue). Nikon RTS2000MP custom laser scanning microscope. See related images 3518, 3519, 3520, 3522.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

2723: iPS cell facility at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research

2723: iPS cell facility at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research

This lab space was designed for work on the induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell collection, part of the NIGMS Human Genetic Cell Repository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research.

Courtney Sill, Coriell Institute for Medical Research

View Media

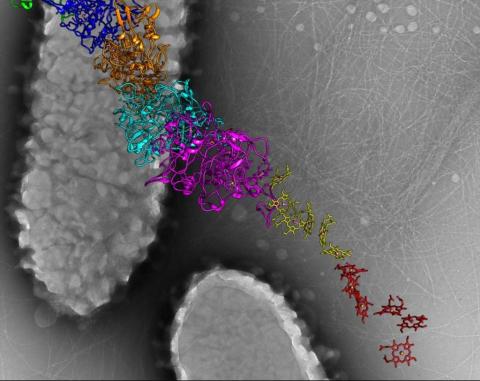

6580: Bacterial nanowire model

6580: Bacterial nanowire model

A model of a Geobacter sulfurreducens nanowire created from cryo-electron microscopy images. The bacterium conducts electricity through these nanowires, which are made up of protein and iron-containing molecules.

Edward Egelman, University of Virginia.

View Media

3558: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish - lateral view

3558: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish - lateral view

Luciferase-based imaging enables visualization and quantification of internal organs and transplanted cells in live adult zebrafish. In this image, a cardiac muscle-restricted promoter drives firefly luciferase expression (lateral view).

For imagery of both the lateral and overhead view go to 3556.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For more information about the illumated area go to 3559.

For imagery of both the lateral and overhead view go to 3556.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For more information about the illumated area go to 3559.

Kenneth Poss, Duke University

View Media

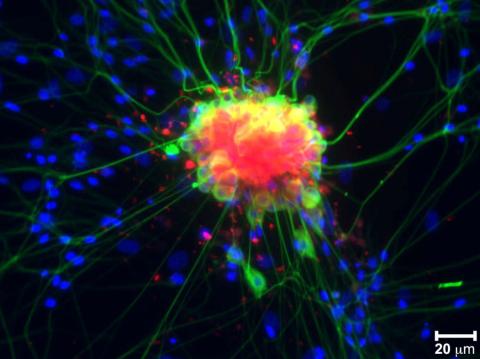

3251: Spinal nerve cells

3251: Spinal nerve cells

Neurons (green) and glial cells from isolated dorsal root ganglia express COX-2 (red) after exposure to an inflammatory stimulus (cell nuclei are blue). Lawrence Marnett and colleagues have demonstrated that certain drugs selectively block COX-2 metabolism of endocannabinoids -- naturally occurring analgesic molecules -- in stimulated dorsal root ganglia. Featured in the October 20, 2011 issue of Biomedical Beat.

Lawrence Marnett, Vanderbilt University

View Media

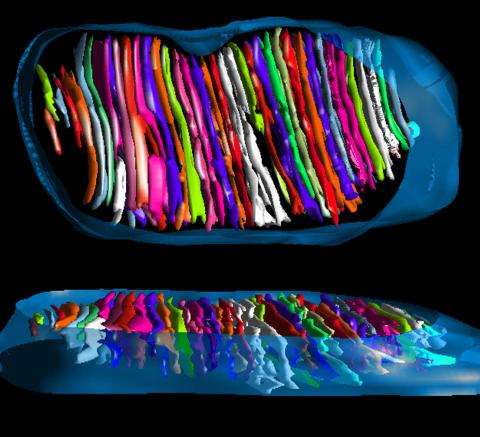

3662: Mitochondrion from insect flight muscle

3662: Mitochondrion from insect flight muscle

This is a tomographic reconstruction of a mitochondrion from an insect flight muscle. Mitochondria are cellular compartments that are best known as the powerhouses that convert energy from the food into energy that runs a range of biological processes. Nearly all our cells have mitochondria.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media

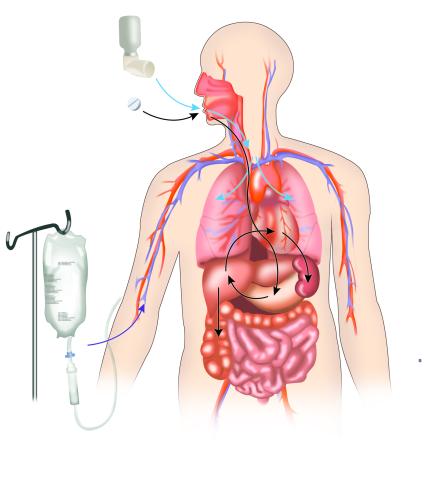

2527: A drug's life in the body

2527: A drug's life in the body

A drug's life in the body. Medicines taken by mouth pass through the liver before they are absorbed into the bloodstream. Other forms of drug administration bypass the liver, entering the blood directly. See 2528 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in Medicines By Design.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

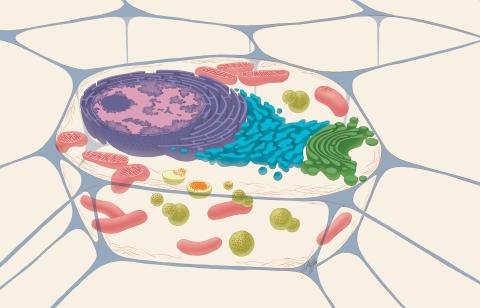

1274: Animal cell

1274: Animal cell

A typical animal cell, sliced open to reveal a cross-section of organelles.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

2438: Hydra 02

2438: Hydra 02

Hydra magnipapillata is an invertebrate animal used as a model organism to study developmental questions, for example the formation of the body axis.

Hiroshi Shimizu, National Institute of Genetics in Mishima, Japan

View Media

3339: Single-Molecule Imaging

3339: Single-Molecule Imaging

This is a super-resolution light microscope image taken by Hiro Hakozaki and Masa Hoshijima of NCMIR. The image contains highlighted calcium channels in cardiac muscle using a technique called dSTORM. The microscope used in the NCMIR lab was built by Hiro Hakozaki.

Tom Deerinck, NCMIR

View Media

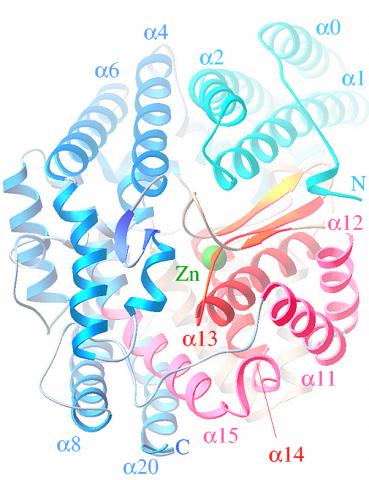

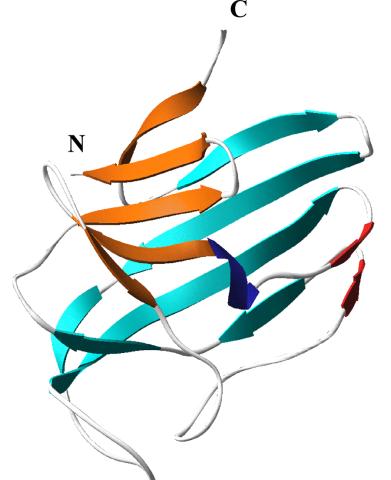

2373: Oligoendopeptidase F from B. stearothermophilus

2373: Oligoendopeptidase F from B. stearothermophilus

Crystal structure of oligoendopeptidase F, a protein slicing enzyme from Bacillus stearothermophilus, a bacterium that can cause food products to spoil. The crystal was formed using a microfluidic capillary, a device that enables scientists to independently control the parameters for protein crystal nucleation and growth. Featured as one of the July 2007 Protein Structure Initiative Structures of the Month.

Accelerated Technologies Center for Gene to 3D Structure/Midwest Center for Structural Genomics

View Media

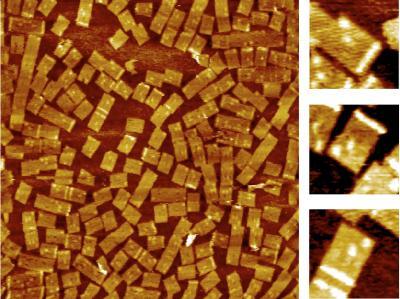

2455: Golden gene chips

2455: Golden gene chips

A team of chemists and physicists used nanotechnology and DNA's ability to self-assemble with matching RNA to create a new kind of chip for measuring gene activity. When RNA of a gene of interest binds to a DNA tile (gold squares), it creates a raised surface (white areas) that can be detected by a powerful microscope. This nanochip approach offers manufacturing and usage advantages over existing gene chips and is a key step toward detecting gene activity in a single cell. Featured in the February 20, 2008, issue of Biomedical Beat.

Hao Yan and Yonggang Ke, Arizona State University

View Media

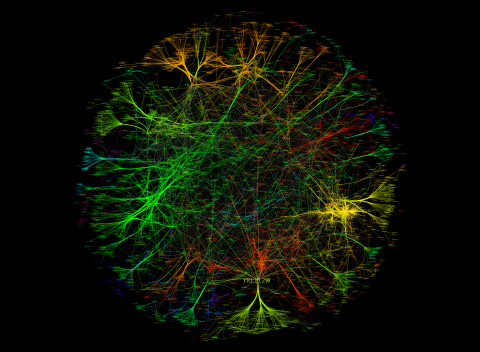

3733: A molecular interaction network in yeast 3

3733: A molecular interaction network in yeast 3

The image visualizes a part of the yeast molecular interaction network. The lines in the network represent connections among genes (shown as little dots) and different-colored networks indicate subnetworks, for instance, those in specific locations or pathways in the cell. Researchers use gene or protein expression data to build these networks; the network shown here was visualized with a program called Cytoscape. By following changes in the architectures of these networks in response to altered environmental conditions, scientists can home in on those genes that become central "hubs" (highly connected genes), for example, when a cell encounters stress. They can then further investigate the precise role of these genes to uncover how a cell's molecular machinery deals with stress or other factors. Related to images 3730 and 3732.

Keiichiro Ono, UCSD

View Media

1085: Natcher Building 05

1085: Natcher Building 05

NIGMS staff are located in the Natcher Building on the NIH campus.

Alisa Machalek, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

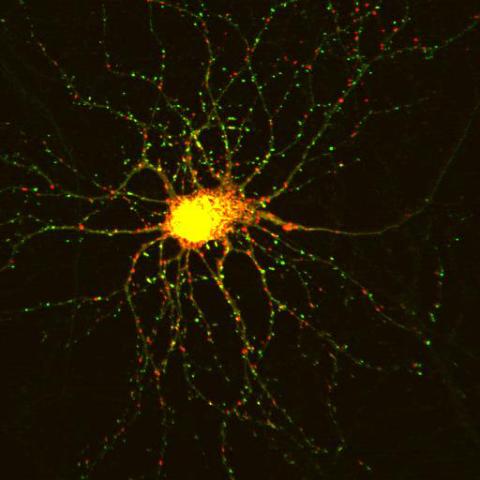

3509: Neuron with labeled synapses

3509: Neuron with labeled synapses

In this image, recombinant probes known as FingRs (Fibronectin Intrabodies Generated by mRNA display) were expressed in a cortical neuron, where they attached fluorescent proteins to either PSD95 (green) or Gephyrin (red). PSD-95 is a marker for synaptic strength at excitatory postsynaptic sites, and Gephyrin plays a similar role at inhibitory postsynaptic sites. Thus, using FingRs it is possible to obtain a map of synaptic connections onto a particular neuron in a living cell in real time.

Don Arnold and Richard Roberts, University of Southern California.

View Media

2754: Myosin V binding to actin

2754: Myosin V binding to actin

This simulation of myosin V binding to actin was created using the software tool Protein Mechanica. With Protein Mechanica, researchers can construct models using information from a variety of sources: crystallography, cryo-EM, secondary structure descriptions, as well as user-defined solid shapes, such as spheres and cylinders. The goal is to enable experimentalists to quickly and easily simulate how different parts of a molecule interact.

Simbios, NIH Center for Biomedical Computation at Stanford

View Media

6586: Cell-like compartments from frog eggs 3

6586: Cell-like compartments from frog eggs 3

Cell-like compartments that spontaneously emerged from scrambled frog eggs. Endoplasmic reticulum (red) and microtubules (green) are visible. Image created using epifluorescence microscopy.

For more photos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6584, 6585, 6591, 6592, and 6593.

For videos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6587, 6588, 6589, and 6590.

Xianrui Cheng, Stanford University School of Medicine.

View Media

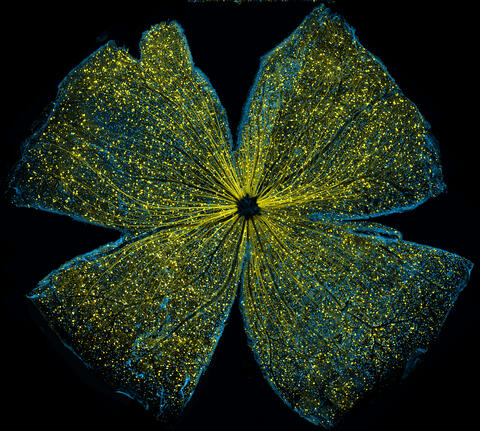

5793: Mouse retina

5793: Mouse retina

What looks like the gossamer wings of a butterfly is actually the retina of a mouse, delicately snipped to lay flat and sparkling with fluorescent molecules. The image is from a research project investigating the promise of gene therapy for glaucoma. It was created at an NIGMS-funded advanced microscopy facility that develops technology for imaging across many scales, from whole organisms to cells to individual molecules.

The ability to obtain high-resolution imaging of tissue as large as whole mouse retinas was made possible by a technique called large-scale mosaic confocal microscopy, which was pioneered by the NIGMS-funded National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research. The technique is similar to Google Earth in that it computationally stitches together many small, high-resolution images.

The ability to obtain high-resolution imaging of tissue as large as whole mouse retinas was made possible by a technique called large-scale mosaic confocal microscopy, which was pioneered by the NIGMS-funded National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research. The technique is similar to Google Earth in that it computationally stitches together many small, high-resolution images.

Tom Deerinck and Keunyoung (“Christine”) Kim, NCMIR

View Media

5872: Mouse retina close-up

5872: Mouse retina close-up

Keunyoung ("Christine") Kim National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

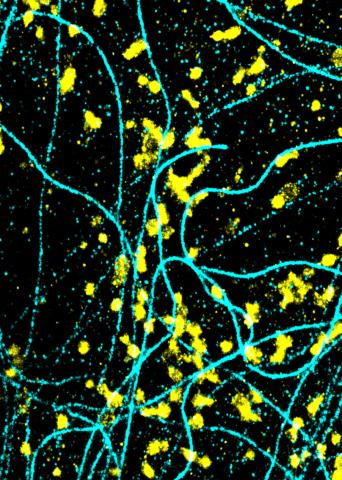

6889: Lysosomes and microtubules

6889: Lysosomes and microtubules

Lysosomes (yellow) and detyrosinated microtubules (light blue). Lysosomes are bubblelike organelles that take in molecules and use enzymes to break them down. Microtubules are strong, hollow fibers that provide structural support to cells. The researchers who took this image found that in epithelial cells, detyrosinated microtubules are a small subset of fibers, and they concentrate lysosomes around themselves. This image was captured using Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy (STORM).

Related to images 6890, 6891, and 6892.

Related to images 6890, 6891, and 6892.

Melike Lakadamyali, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

View Media

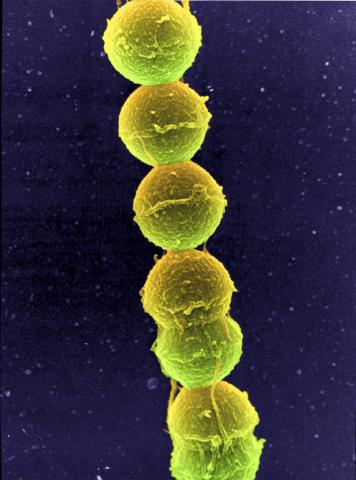

1157: Streptococcus bacteria

1157: Streptococcus bacteria

Image of Streptococcus, a type (genus) of spherical bacteria that can colonize the throat and back of the mouth. Stroptococci often occur in pairs or in chains, as shown here.

Tina Weatherby Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

View Media

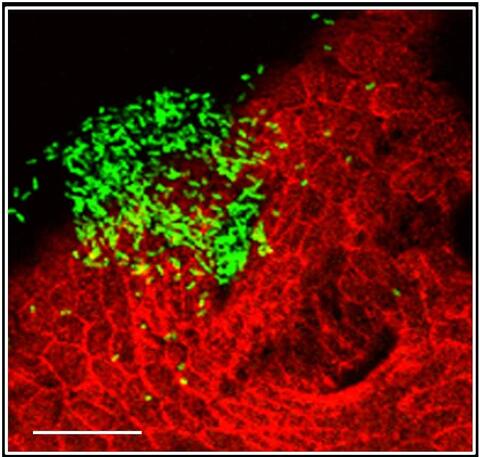

7019: Bacterial cells aggregated above a light-organ pore of the Hawaiian bobtail squid

7019: Bacterial cells aggregated above a light-organ pore of the Hawaiian bobtail squid

The beating of cilia on the outside of the Hawaiian bobtail squid’s light organ concentrates Vibrio fischeri cells (green) present in the seawater into aggregates near the pore-containing tissue (red). From there, the bacterial cells (~2 mm) swim to the pores and migrate through a bottleneck into the interior crypts where a population of symbionts grow and remain for the life of the host. This image was taken using confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Related to images 7016, 7017, 7018, and 7020.

Related to images 7016, 7017, 7018, and 7020.

Margaret J. McFall-Ngai, Carnegie Institution for Science/California Institute of Technology, and Edward G. Ruby, California Institute of Technology.

View Media

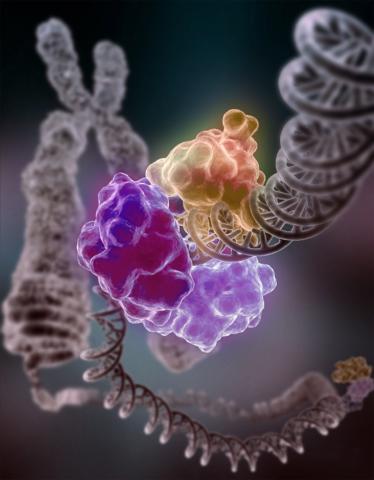

3493: Repairing DNA

3493: Repairing DNA

Like a watch wrapped around a wrist, a special enzyme encircles the double helix to repair a broken strand of DNA. Without molecules that can mend such breaks, cells can malfunction, die, or become cancerous. Related to image 2330.

Tom Ellenberger, Washington University School of Medicine

View Media

2728: Sponge

2728: Sponge

Many of today's medicines come from products found in nature, such as this sponge found off the coast of Palau in the Pacific Ocean. Chemists have synthesized a compound called Palau'amine, which appears to act against cancer, bacteria and fungi. In doing so, they invented a new chemical technique that will empower the synthesis of other challenging molecules.

Phil Baran, Scripps Research Institute

View Media

3719: CRISPR illustration

3719: CRISPR illustration

This illustration shows, in simplified terms, how the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used as a gene-editing tool.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and download the four images of the CRIPSR illustration here.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and download the four images of the CRIPSR illustration here.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

View Media

2379: Secreted protein from Mycobacteria

2379: Secreted protein from Mycobacteria

Model of a major secreted protein of unknown function, which is only found in mycobacteria, the class of bacteria that causes tuberculosis. Based on structural similarity, this protein may be involved in host-bacterial interactions.

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Center, PSI

View Media

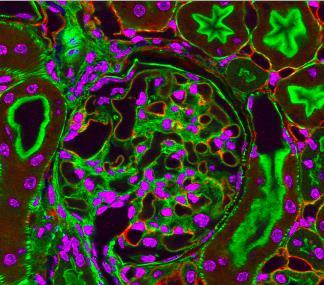

3725: Fluorescent microscopy of kidney tissue--close-up

3725: Fluorescent microscopy of kidney tissue--close-up

This photograph of kidney tissue, taken using fluorescent light microscopy, shows a close-up view of part of image 3723. Kidneys filter the blood, removing waste and excessive fluid, which is excreted in urine. The filtration system is made up of components that include glomeruli (for example, the round structure taking up much of the image's center is a glomerulus) and tubules (seen in cross-section here with their inner lining stained green). Related to image 3675 .

Tom Deerinck , National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media

3432: Mouse mammary cells lacking anti-cancer protein

3432: Mouse mammary cells lacking anti-cancer protein

Shortly after a pregnant woman gives birth, her breasts start to secrete milk. This process is triggered by hormonal and genetic cues, including the protein Elf5. Scientists discovered that Elf5 also has another job--it staves off cancer. Early in the development of breast cancer, human breast cells often lose Elf5 proteins. Cells without Elf5 change shape and spread readily--properties associated with metastasis. This image shows cells in the mouse mammary gland that are lacking Elf5, leading to the overproduction of other proteins (red) that increase the likelihood of metastasis.

Nature Cell Biology, November 2012, Volume 14 No 11 pp1113-1231

View Media

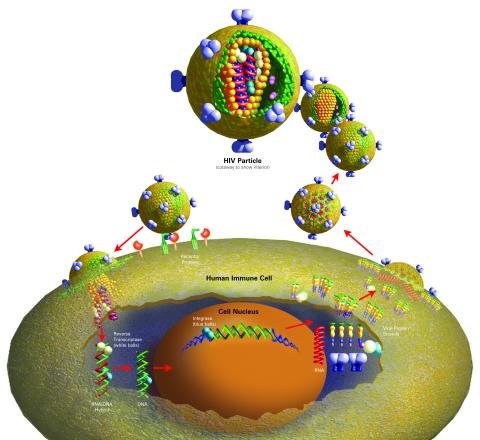

2514: Life of an AIDS virus (with labels)

2514: Life of an AIDS virus (with labels)

HIV is a retrovirus, a type of virus that carries its genetic material not as DNA but as RNA. Long before anyone had heard of HIV, researchers in labs all over the world studied retroviruses, tracing out their life cycle and identifying the key proteins the viruses use to infect cells. When HIV was identified as a retrovirus, these studies gave AIDS researchers an immediate jump-start. The previously identified viral proteins became initial drug targets. See images 2513 and 2515 for other versions of this illustration. Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

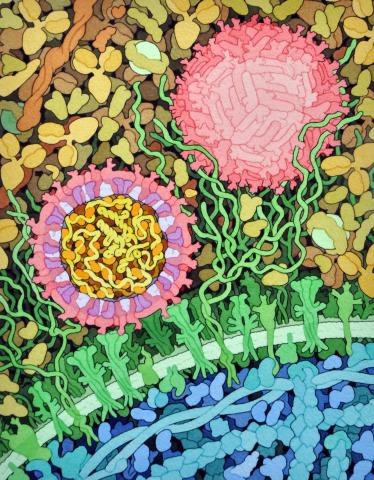

6998: Zika virus

6998: Zika virus

Zika virus is shown in cross section at center left. On the outside, it includes envelope protein (red) and membrane protein (magenta) embedded in a lipid membrane (light purple). Inside, the RNA genome (yellow) is associated with capsid proteins (orange). The viruses are shown interacting with receptors on the cell surface (green) and are surrounded by blood plasma molecules at the top.

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

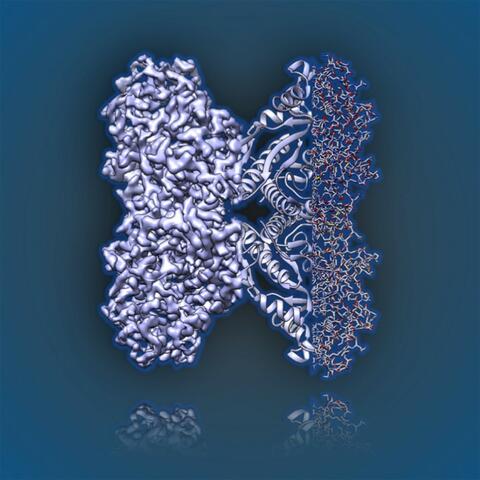

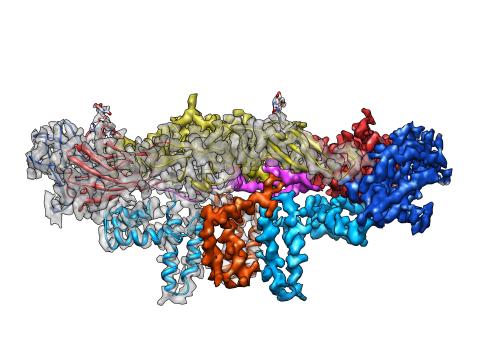

6350: Aldolase

6350: Aldolase

2.5Å resolution reconstruction of rabbit muscle aldolase collected on a FEI/Thermo Fisher Titan Krios with energy filter and image corrector.

National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy http://nramm.nysbc.org/nramm-images/ Source: Bridget Carragher

View Media

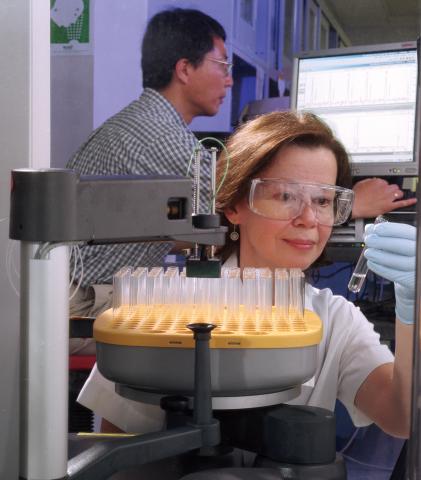

2375: Protein purification robot

2375: Protein purification robot

Irina Dementieva, a biochemist, and Youngchang Kim, a biophysicist and crystallographer, work with the first robot of its type in the U.S. to automate protein purification. The robot, which is housed in a refrigerator, is an integral part of the Midwest Structural Genomics Center's plan to automate the protein crystallography process.

Midwest Center for Structural Genomics

View Media

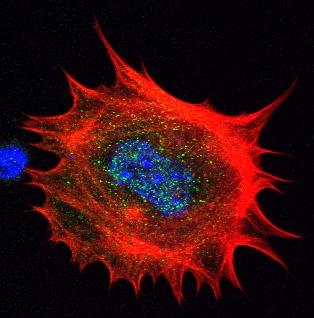

3329: Spreading Cells- 02

3329: Spreading Cells- 02

Cells move forward with lamellipodia and filopodia supported by networks and bundles of actin filaments. Proper, controlled cell movement is a complex process. Recent research has shown that an actin-polymerizing factor called the Arp2/3 complex is the key component of the actin polymerization engine that drives amoeboid cell motility. ARPC3, a component of the Arp2/3 complex, plays a critical role in actin nucleation. In this photo, the ARPC3-/- fibroblast cells were fixed and stained with Alexa 546 phalloidin for F-actin (red), Arp2 (green), and DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). Arp2, a subunit of the Arp2/3 complex, is absent in the filopodi-like structures based leading edge of ARPC3-/- fibroblasts cells. Related to images 3328, 3330, 3331, 3332, and 3333.

Rong Li and Praveen Suraneni, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

View Media

2794: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743), structure without hydrogens 01

2794: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743), structure without hydrogens 01

Ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743, brand name Yondelis), was discovered and isolated from a sea squirt, Ecteinascidia turbinata, by NIGMS grantee Kenneth Rinehart at the University of Illinois. It was synthesized by NIGMS grantees E.J. Corey and later by Samuel Danishefsky. Multiple versions of this structure are available as entries 2790-2797.

Timothy Jamison, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

View Media

1016: Lily mitosis 06

1016: Lily mitosis 06

A light microscope image of a cell from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue. Here, condensed chromosomes are clearly visible and are starting to line up.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

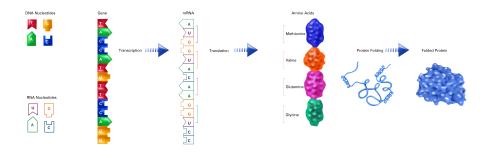

2510: From DNA to Protein (labeled)

2510: From DNA to Protein (labeled)

The genetic code in DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is translated into proteins with specific sequences. During transcription, nucleotides in DNA are copied into RNA, where they are read three at a time to encode the amino acids in a protein. Many parts of a protein fold as the amino acids are strung together.

See image 2509 for an unlabeled version of this illustration.

Featured in The Structures of Life.

See image 2509 for an unlabeled version of this illustration.

Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

1311: Housekeeping cell illustration

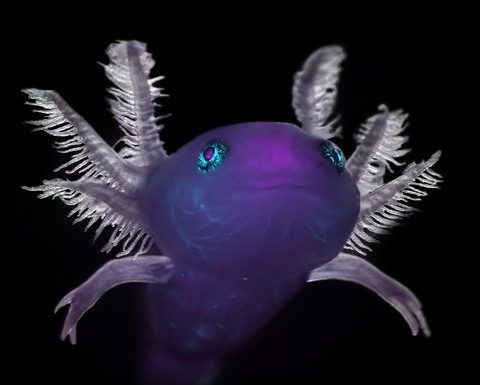

6932: Axolotl

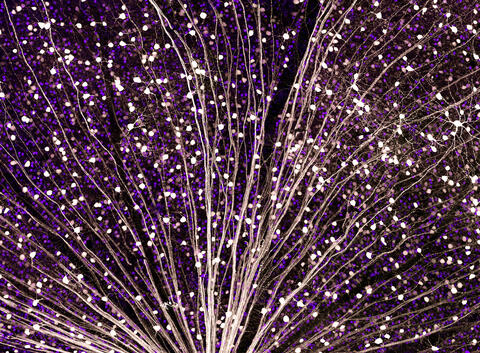

6932: Axolotl

An axolotl—a type of salamander—that has been genetically modified so that its developing nervous system glows purple and its Schwann cell nuclei appear light blue. Schwann cells insulate and provide nutrients to peripheral nerve cells. Researchers often study axolotls for their extensive regenerative abilities. They can regrow tails, limbs, spinal cords, brains, and more. The researcher who took this image focuses on the role of the peripheral nervous system during limb regeneration.

This image was captured using a stereo microscope.

Related to images 6927 and 6928.

This image was captured using a stereo microscope.

Related to images 6927 and 6928.

Prayag Murawala, MDI Biological Laboratory and Hannover Medical School.

View Media

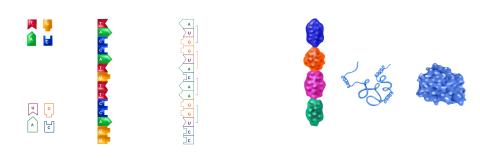

2509: From DNA to Protein

2509: From DNA to Protein

Nucleotides in DNA are copied into RNA, where they are read three at a time to encode the amino acids in a protein. Many parts of a protein fold as the amino acids are strung together.

See image 2510 for a labeled version of this illustration.

Featured in The Structures of Life.

See image 2510 for a labeled version of this illustration.

Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

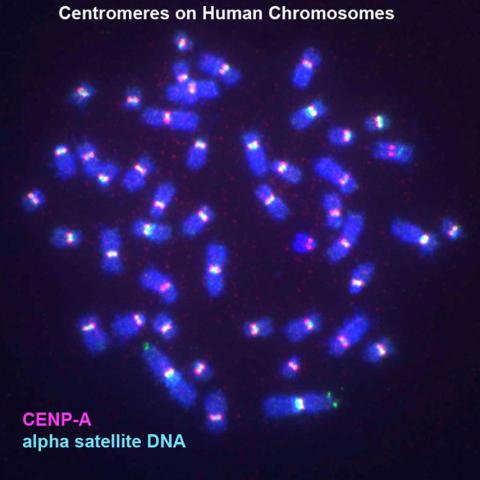

3255: Centromeres on human chromosomes

3255: Centromeres on human chromosomes

Human metaphase chromosomes are visible with fluorescence in vitro hybridization (FISH). Centromeric alpha satellite DNA (green) are found in the heterochromatin at each centromere. Immunofluorescence with CENP-A (red) shows the centromere-specific histone H3 variant that specifies the kinetochore.

Peter Warburton, Mount Sinai School of Medicine

View Media

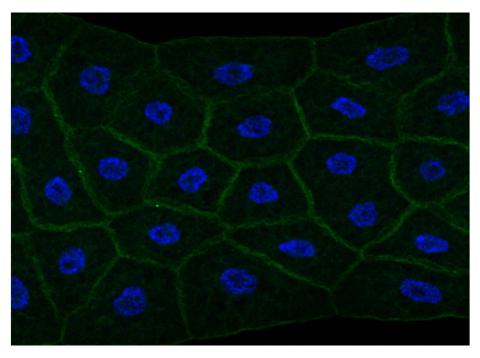

2757: Draper, shown in the fatbody of a Drosophila melanogaster larva

2757: Draper, shown in the fatbody of a Drosophila melanogaster larva

The fly fatbody is a nutrient storage and mobilization organ akin to the mammalian liver. The engulfment receptor Draper (green) is located at the cell surface of fatbody cells. The cell nuclei are shown in blue.

Christina McPhee and Eric Baehrecke, University of Massachusetts Medical School

View Media

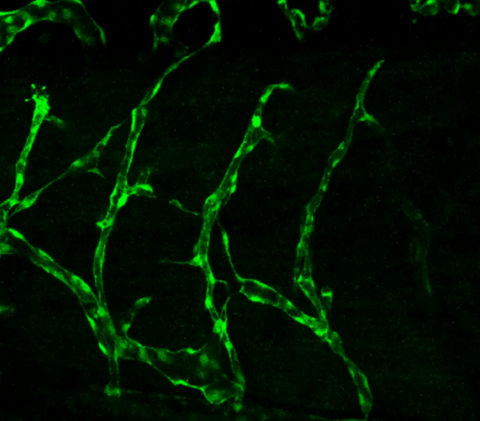

3403: Disrupted vascular development in frog embryos

3403: Disrupted vascular development in frog embryos

Disassembly of vasculature in kdr:GFP frogs following addition of 250 µM TBZ. Related to images 3404 and 3505.

Hye Ji Cha, University of Texas at Austin

View Media

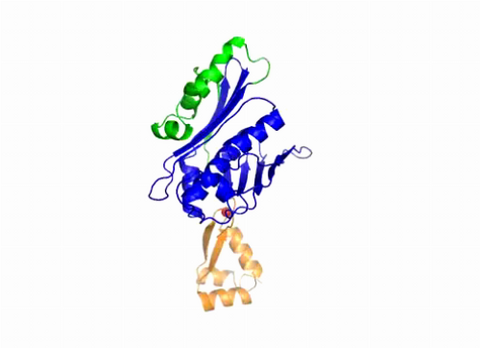

3402: Hsp33 Heat Shock Protein Inactive to Active

3402: Hsp33 Heat Shock Protein Inactive to Active

When the heat shock protein hsp33 is folded, it is inactive and contains a zinc ion, stabilizing the redox sensitive domain (orange). In the presence of an environmental stressor, the protein releases the zinc ion, which leads to the unfolding of the redox domain. This unfolding causes the chaperone to activate by reaching out its "arm" (green) to protect other proteins.

Dana Reichmann, University of Michigan

View Media

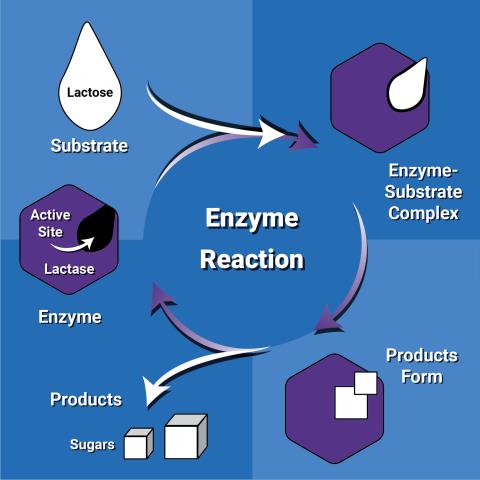

6604: Enzyme reaction

6604: Enzyme reaction

Enzymes speed up chemical reactions by reducing the amount of energy needed for the reactions. The substrate (lactose) binds to the active site of the enzyme (lactase) and is converted into products (sugars).

NIGMS

View Media

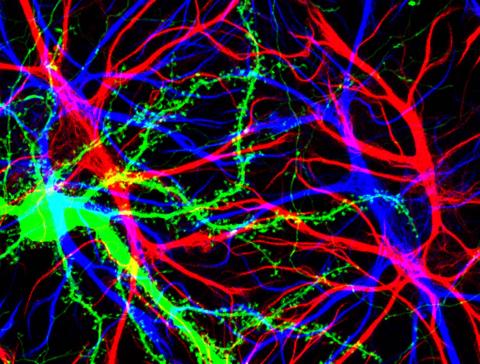

3688: Brain cells in the hippocampus

3688: Brain cells in the hippocampus

Hippocampal cells in culture with a neuron in green, showing hundreds of the small protrusions known as dendritic spines. The dendrites of other neurons are labeled in blue, and adjacent glial cells are shown in red.

Shelley Halpain, UC San Diego

View Media

3758: Dengue virus membrane protein structure

3758: Dengue virus membrane protein structure

Dengue virus is a mosquito-borne illness that infects millions of people in the tropics and subtropics each year. Like many viruses, dengue is enclosed by a protective membrane. The proteins that span this membrane play an important role in the life cycle of the virus. Scientists used cryo-EM to determine the structure of a dengue virus at a 3.5-angstrom resolution to reveal how the membrane proteins undergo major structural changes as the virus matures and infects a host. The image shows a side view of the structure of a protein composed of two smaller proteins, called E and M. Each E and M contributes two molecules to the overall protein structure (called a heterotetramer), which is important for assembling and holding together the viral membrane, i.e., the shell that surrounds the genetic material of the dengue virus. The dengue protein's structure has revealed some portions in the protein that might be good targets for developing medications that could be used to combat dengue virus infections. For more on cryo-EM see the blog post Cryo-Electron Microscopy Reveals Molecules in Ever Greater Detail. You can watch a rotating view of the dengue virus surface structure in video 3748.

Hong Zhou, UCLA

View Media