Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

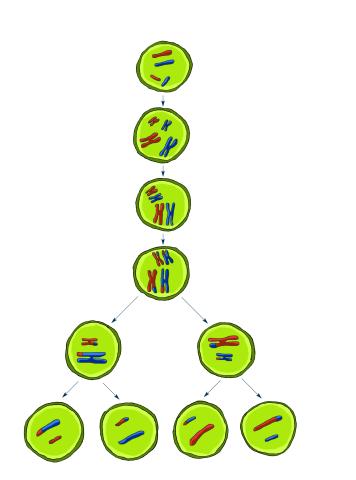

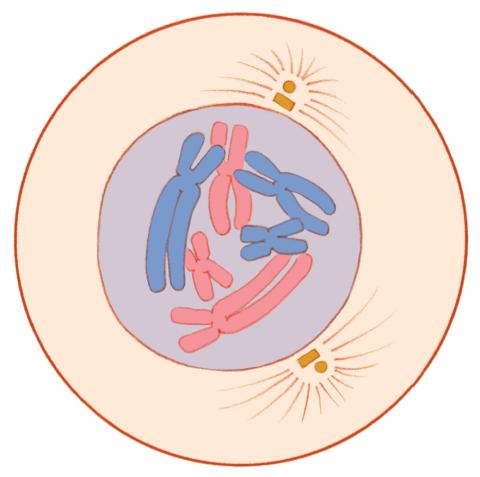

2545: Meiosis illustration

2545: Meiosis illustration

Meiosis is the process whereby a cell reduces its chromosomes from diploid to haploid in creating eggs or sperm. See image 2546 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

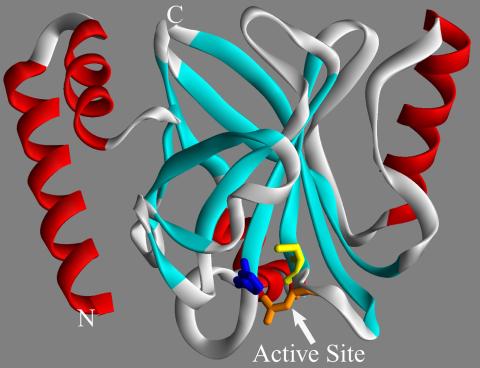

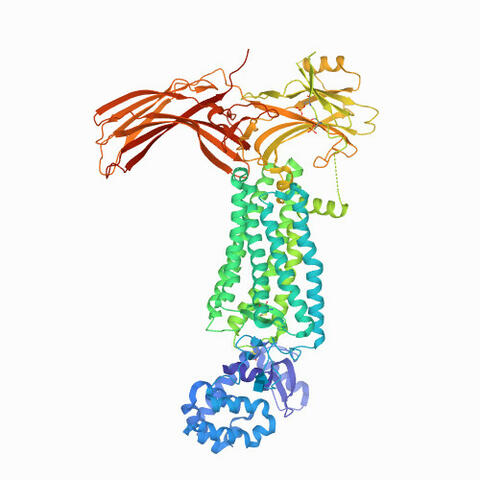

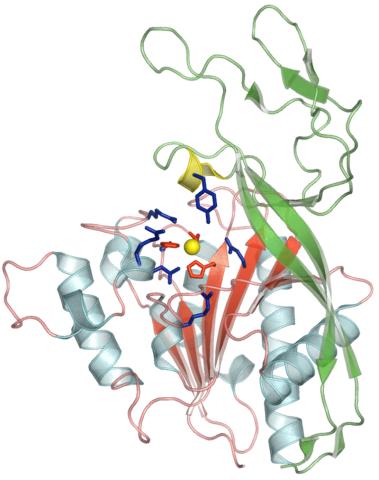

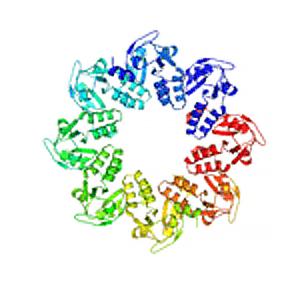

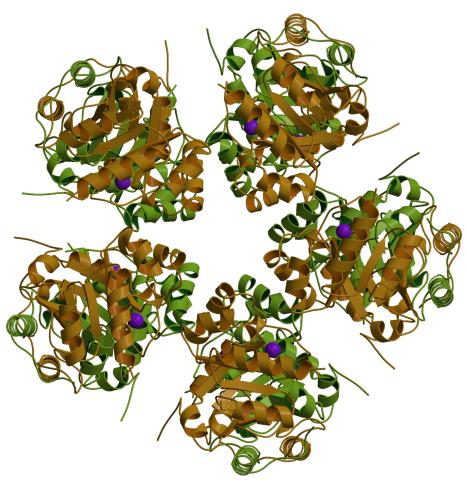

2386: Sortase b from B. anthracis

2386: Sortase b from B. anthracis

Structure of sortase b from the bacterium B. anthracis, which causes anthrax. Sortase b is an enzyme used to rob red blood cells of iron, which the bacteria need to survive.

Midwest Center for Structural Genomics, PSI

View Media

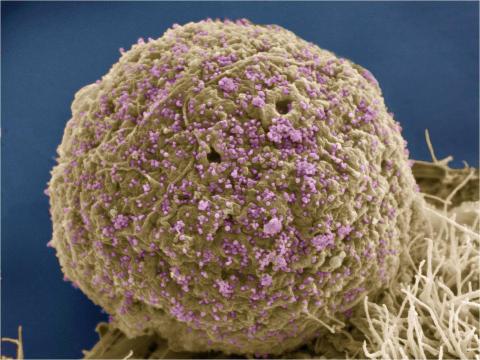

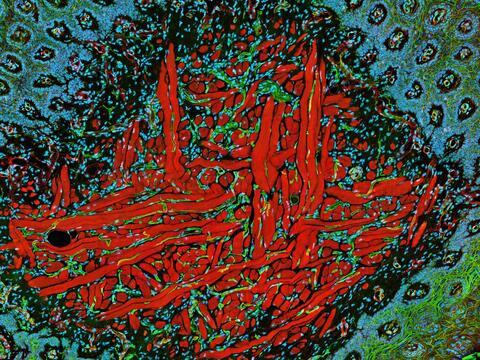

3386: HIV Infected Cell

3386: HIV Infected Cell

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), shown here as tiny purple spheres, causes the disease known as AIDS (for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). HIV can infect multiple cells in your body, including brain cells, but its main target is a cell in the immune system called the CD4 lymphocyte (also called a T-cell or CD4 cell).

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

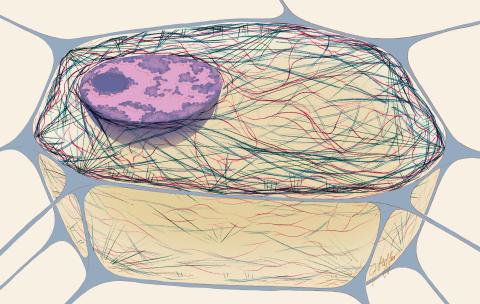

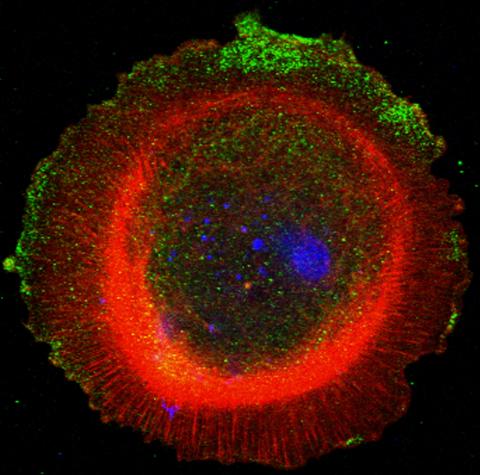

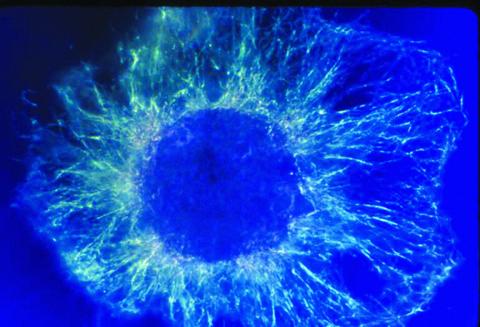

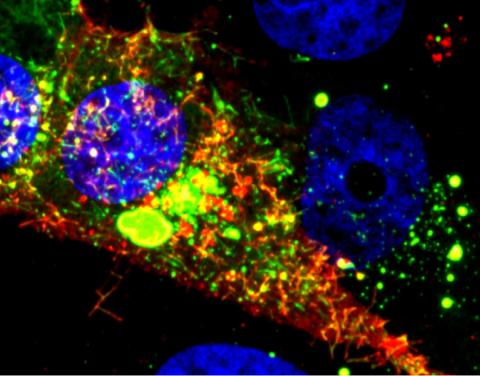

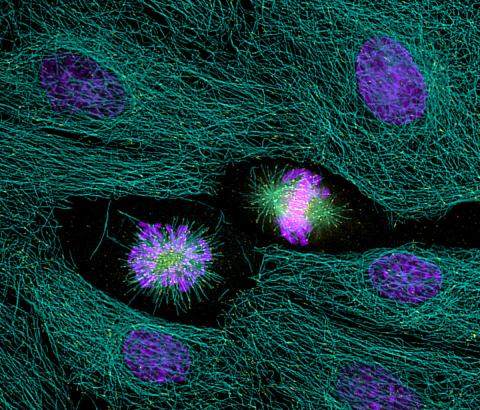

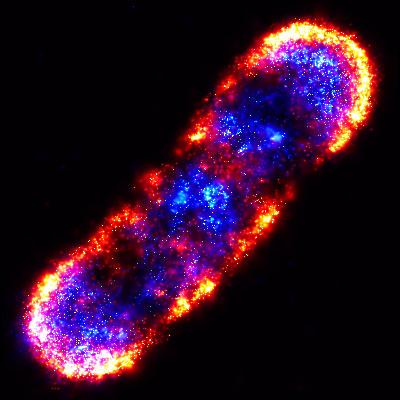

1272: Cytoskeleton

1272: Cytoskeleton

The three fibers of the cytoskeleton--microtubules in blue, intermediate filaments in red, and actin in green--play countless roles in the cell.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

2797: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743), structure without hydrogens 04

2797: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743), structure without hydrogens 04

Ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743, brand name Yondelis), was discovered and isolated from a sea squirt, Ecteinascidia turbinata, by NIGMS grantee Kenneth Rinehart at the University of Illinois. It was synthesized by NIGMS grantees E.J. Corey and later by Samuel Danishefsky. Multiple versions of this structure are available as entries 2790-2797.

Timothy Jamison, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

View Media

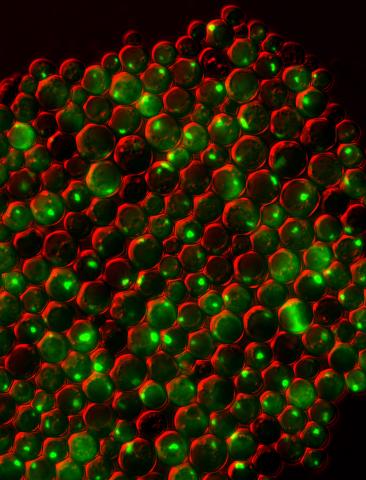

3788: Yeast cells pack a punch

3788: Yeast cells pack a punch

Although they are tiny, microbes that are growing in confined spaces can generate a lot of pressure. In this video, yeast cells grow in a small chamber called a microfluidic bioreactor. As the cells multiply, they begin to bump into and squeeze each other, resulting in periodic bursts of cells moving into different parts of the chamber. The continually growing cells also generate a lot of pressure--the researchers conducting these experiments found that the pressure generated by the cells can be almost five times higher than that in a car tire--about 150 psi, or 10 times the atmospheric pressure. Occasionally, this pressure even caused the small reactor to burst. By tracking the growth of the yeast or other cells and measuring the mechanical forces generated, scientists can simulate microbial growth in various places such as water pumps, sewage lines or catheters to learn how damage to these devices can be prevented. To learn more how researchers used small bioreactors to gauge the pressure generated by growing microbes, see this press release from UC Berkeley.

Oskar Hallatschek, UC Berkeley

View Media

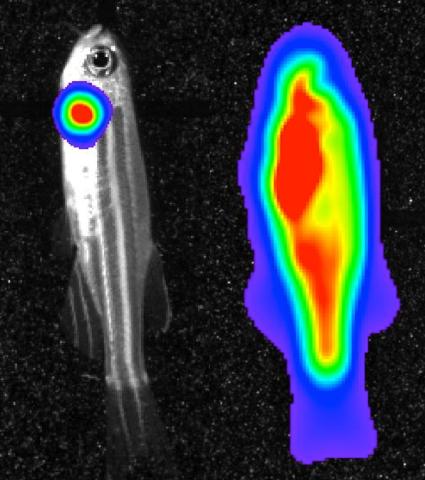

3559: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish 04

3559: Bioluminescent imaging in adult zebrafish 04

Luciferase-based imaging enables visualization and quantification of internal organs and transplanted cells in live adult zebrafish. This image shows how luciferase-based imaging could be used to visualize the heart for regeneration studies (left), or label all tissues for stem cell transplantation (right).

For imagery of both the lateral and overhead view go to 3556.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For imagery of the lateral view go to 3558.

View Media

For imagery of both the lateral and overhead view go to 3556.

For imagery of the overhead view go to 3557.

For imagery of the lateral view go to 3558.

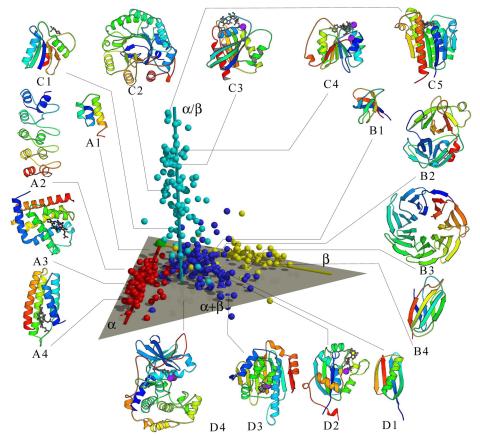

2367: Map of protein structures 02

2367: Map of protein structures 02

A global "map of the protein structure universe" indicating the positions of specific proteins. The preponderance of small, less-structured proteins near the origin, with the more highly structured, large proteins towards the ends of the axes, may suggest the evolution of protein structures.

Berkeley Structural Genomics Center, PSI

View Media

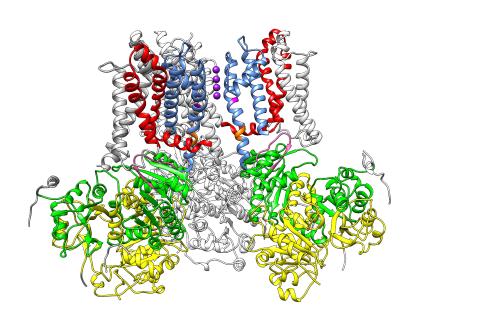

3487: Ion channel

3487: Ion channel

A special "messy" region of a potassium ion channel is important in its function.

Yu Zhoi, Christopher Lingle Laboratory, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

View Media

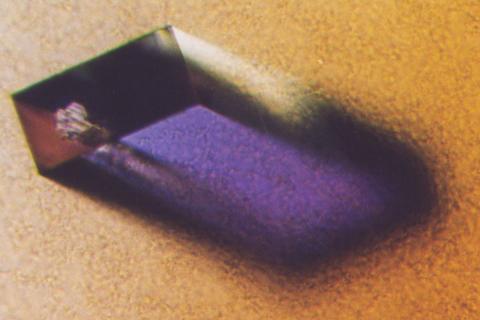

2405: Rabbit GPDA

2405: Rabbit GPDA

A crystal of rabbit GPDA protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

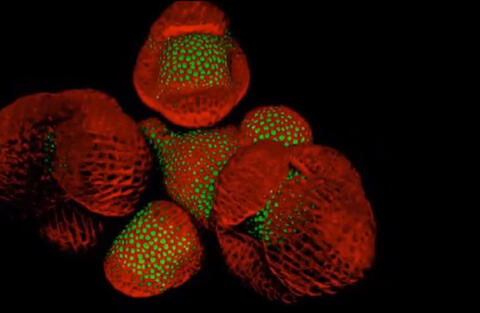

6503: Arabidopsis Thaliana: Flowers Spring to Life

6503: Arabidopsis Thaliana: Flowers Spring to Life

This image capture shows how a single gene, STM, plays a starring role in plant development. This gene acts like a molecular fountain of youth, keeping cells ever-young until it’s time to grow up and commit to making flowers and other plant parts. Because of its ease of use and low cost, Arabidopsis is a favorite model for scientists to learn the basic principles driving tissue growth and regrowth for humans as well as the beautiful plants outside your window. Image captured from video Watch Flowers Spring to Life, featured in the NIH Director's Blog: Watch Flowers Spring to Life.

Nathanaёl Prunet NIH Support: National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

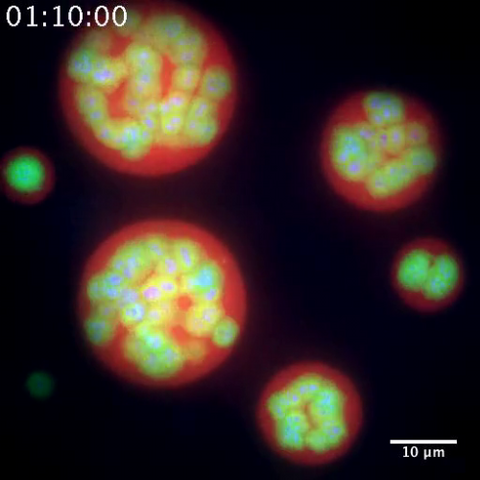

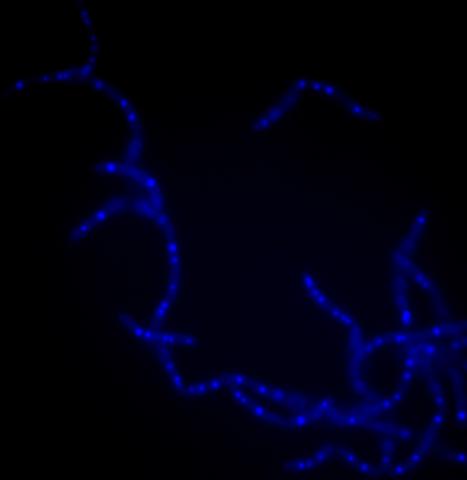

3791: Nucleolus subcompartments spontaneously self-assemble 2

3791: Nucleolus subcompartments spontaneously self-assemble 2

The nucleolus is a small but very important protein complex located in the cell's nucleus. It forms on the chromosomes at the location where the genes for the RNAs are that make up the structure of the ribosome, the indispensable cellular machine that makes proteins from messenger RNAs.

However, how the nucleolus grows and maintains its structure has puzzled scientists for some time. It turns out that even though it looks like a simple liquid blob, it's rather well-organized, consisting of three distinct layers: the fibrillar center, where the RNA polymerase is active; the dense fibrillar component, which is enriched in the protein fibrillarin; and the granular component, which contains a protein called nucleophosmin. Researchers have now discovered that this multilayer structure of the nucleolus arises from differences in how the proteins in each compartment mix with water and with each other. These differences let the proteins readily separate from each other into the three nucleolus compartments.

This video of nucleoli in the eggs of a commonly used lab animal, the frog Xenopus laevis, shows how each of the compartments (the granular component is shown in red, the fibrillarin in yellow-green, and the fibrillar center in blue) spontaneously fuse with each other on encounter without mixing with the other compartments.

For more details on this research, see this press release from Princeton. Related to video 3789, image 3792 and image 3793.

However, how the nucleolus grows and maintains its structure has puzzled scientists for some time. It turns out that even though it looks like a simple liquid blob, it's rather well-organized, consisting of three distinct layers: the fibrillar center, where the RNA polymerase is active; the dense fibrillar component, which is enriched in the protein fibrillarin; and the granular component, which contains a protein called nucleophosmin. Researchers have now discovered that this multilayer structure of the nucleolus arises from differences in how the proteins in each compartment mix with water and with each other. These differences let the proteins readily separate from each other into the three nucleolus compartments.

This video of nucleoli in the eggs of a commonly used lab animal, the frog Xenopus laevis, shows how each of the compartments (the granular component is shown in red, the fibrillarin in yellow-green, and the fibrillar center in blue) spontaneously fuse with each other on encounter without mixing with the other compartments.

For more details on this research, see this press release from Princeton. Related to video 3789, image 3792 and image 3793.

Nilesh Vaidya, Princeton University

View Media

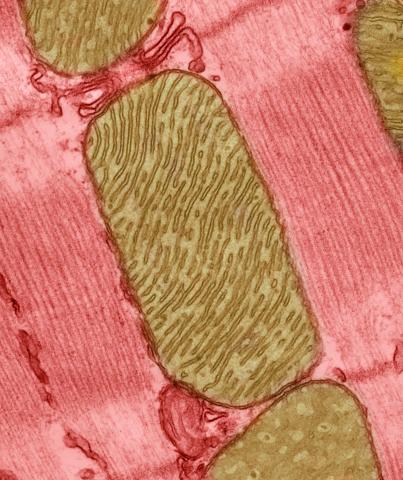

3664: Mitochondria from rat heart muscle cell_2

3664: Mitochondria from rat heart muscle cell_2

These mitochondria (brown) are from the heart muscle cell of a rat. Mitochondria have an inner membrane that folds in many places (and that appears here as striations). This folding vastly increases the surface area for energy production. Nearly all our cells have mitochondria. Related to image 3661.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media

3330: mDia1 antibody staining-01

3330: mDia1 antibody staining-01

Cells move forward with lamellipodia and filopodia supported by networks and bundles of actin filaments. Proper, controlled cell movement is a complex process. Recent research has shown that an actin-polymerizing factor called the Arp2/3 complex is the key component of the actin polymerization engine that drives amoeboid cell motility. ARPC3, a component of the Arp2/3 complex, plays a critical role in actin nucleation. In this photo, the ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells were fixed and stained with Alexa 546 phalloidin for F-actin (red), mDia1 (green), and DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). mDia1 is localized at the lamellipodia of ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells. Related to images 3328, 3329, 3331, 3332, and 3333.

Rong Li and Praveen Suraneni, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

View Media

1086: Natcher Building 06

1086: Natcher Building 06

NIGMS staff are located in the Natcher Building on the NIH campus.

Alisa Machalek, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

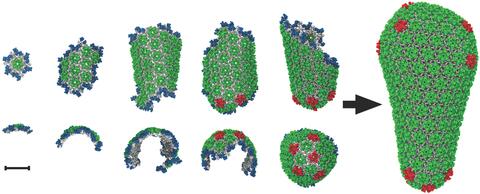

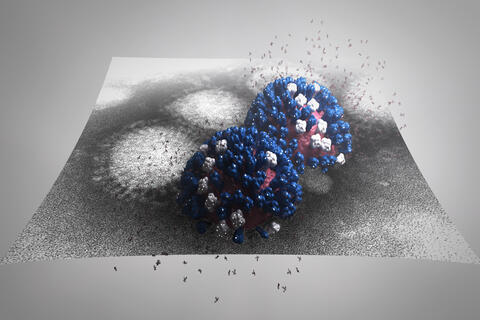

5729: Assembly of the HIV capsid

5729: Assembly of the HIV capsid

The HIV capsid is a pear-shaped structure that is made of proteins the virus needs to mature and become infective. The capsid is inside the virus and delivers the virus' genetic information into a human cell. To better understand how the HIV capsid does this feat, scientists have used computer programs to simulate its assembly. This image shows a series of snapshots of the steps that grow the HIV capsid. A model of a complete capsid is shown on the far right of the image for comparison; the green, blue and red colors indicate different configurations of the capsid protein that make up the capsid “shell.” The bar in the left corner represents a length of 20 nanometers, which is less than a tenth the size of the smallest bacterium. Computer models like this also may be used to reconstruct the assembly of the capsids of other important viruses, such as Ebola or the Zika virus. The studies reporting this research were published in Nature Communications and Nature. To learn more about how researchers used computer simulations to track the assembly of the HIV capsid, see this press release from the University of Chicago.

John Grime and Gregory Voth, The University of Chicago

View Media

1058: Lily mitosis 01

1058: Lily mitosis 01

A light microscope image shows the chromosomes, stained dark blue, in a dividing cell of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

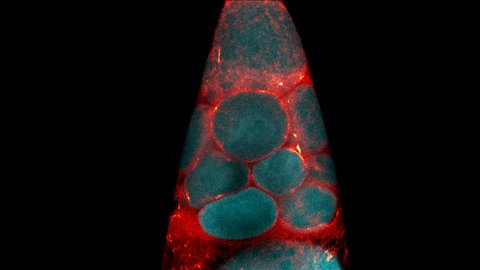

6754: Fruit fly nurse cells transporting their contents during egg development

6754: Fruit fly nurse cells transporting their contents during egg development

In many animals, the egg cell develops alongside sister cells. These sister cells are called nurse cells in the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), and their job is to “nurse” an immature egg cell, or oocyte. Toward the end of oocyte development, the nurse cells transfer all their contents into the oocyte in a process called nurse cell dumping. This video captures this transfer, showing significant shape changes on the part of the nurse cells (blue), which are powered by wavelike activity of the protein myosin (red). Researchers created the video using a confocal laser scanning microscope. Related to image 6753.

Adam C. Martin, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

View Media

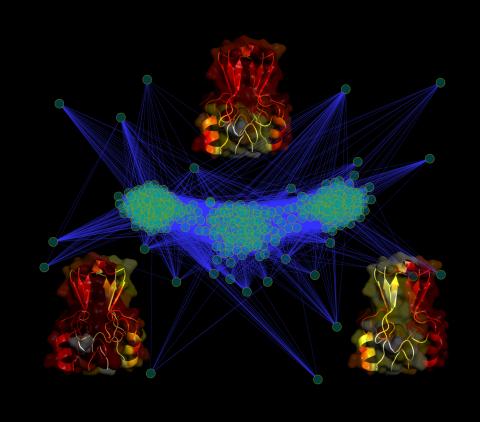

3295: Cluster analysis of mysterious protein

3295: Cluster analysis of mysterious protein

Researchers use cluster analysis to study protein shape and function. Each green circle represents one potential shape of the protein mitoNEET. The longer the blue line between two circles, the greater the differences between the shapes. Most shapes are similar; they fall into three clusters that are represented by the three images of the protein. From a Rice University news release. Graduate student Elizabeth Baxter and Patricia Jennings, professor of chemistry and biochemistry at UCSD, collaborated with José Onuchic, a physicist at Rice University, on this work.

Patricia Jennings and Elizabeth Baxter, University of California, San Diego

View Media

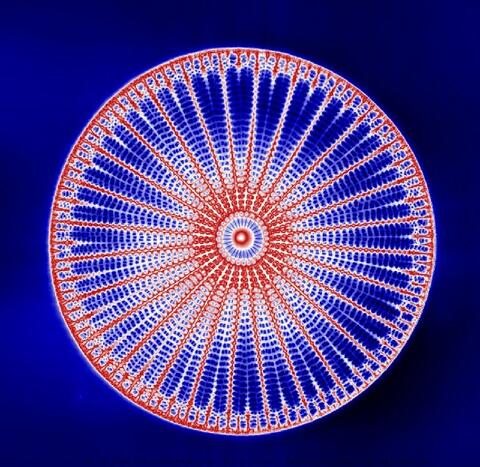

6902: Arachnoidiscus diatom

6902: Arachnoidiscus diatom

An Arachnoidiscus diatom with a diameter of 190µm. Diatoms are microscopic algae that have cell walls made of silica, which is the strongest known biological material relative to its density. In Arachnoidiscus, the cell wall is a radially symmetric pillbox-like shell composed of overlapping halves that contain intricate and delicate patterns. Sometimes, Arachnoidiscus is called “a wheel of glass.”

This image was taken with the orientation-independent differential interference contrast microscope.

This image was taken with the orientation-independent differential interference contrast microscope.

Michael Shribak, Marine Biological Laboratory/University of Chicago.

View Media

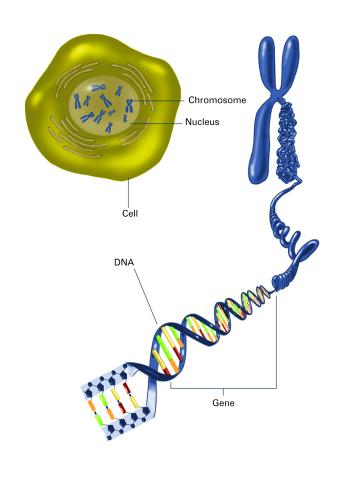

2540: Chromosome inside nucleus (with labels)

2540: Chromosome inside nucleus (with labels)

The long, stringy DNA that makes up genes is spooled within chromosomes inside the nucleus of a cell. (Note that a gene would actually be a much longer stretch of DNA than what is shown here.) See image 2539 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

1019: Lily mitosis 13

1019: Lily mitosis 13

A light microscope image of cells from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue. Here, two cells have formed after a round of mitosis.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

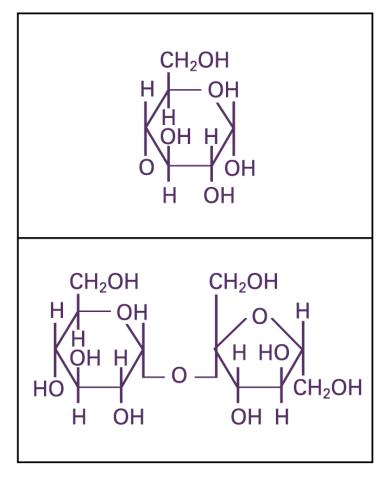

2500: Glucose and sucrose

2500: Glucose and sucrose

Glucose (top) and sucrose (bottom) are sugars made of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. Carbohydrates include simple sugars like these and are the main source of energy for the human body.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

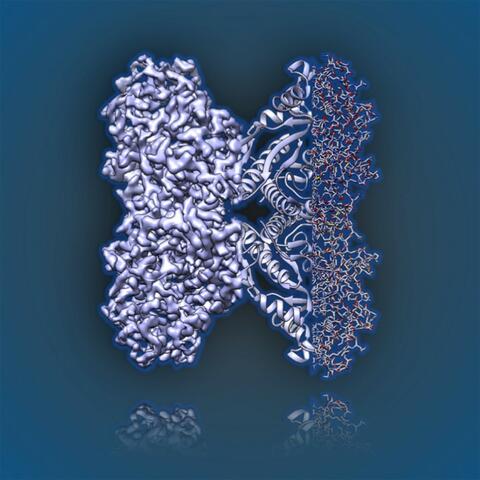

6350: Aldolase

6350: Aldolase

2.5Å resolution reconstruction of rabbit muscle aldolase collected on a FEI/Thermo Fisher Titan Krios with energy filter and image corrector.

National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy http://nramm.nysbc.org/nramm-images/ Source: Bridget Carragher

View Media

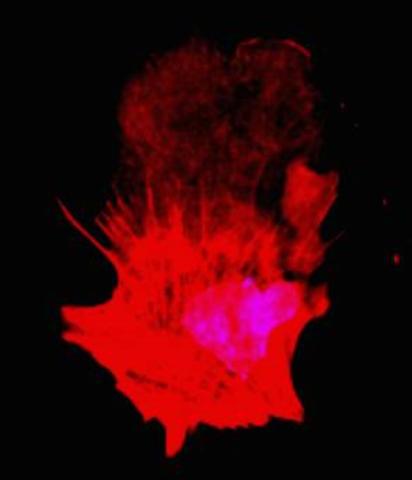

3567: RSV-Infected Cell

3567: RSV-Infected Cell

Viral RNA (red) in an RSV-infected cell. More information about the research behind this image can be found in a Biomedical Beat Blog posting from January 2014.

Eric Alonas and Philip Santangelo, Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University

View Media

6768: Rhodopsin bound to visual arrestin

6768: Rhodopsin bound to visual arrestin

Rhodopsin is a pigment in the rod cells of the retina (back of the eye). It is extremely light-sensitive, supporting vision in low-light conditions. Here, it is attached to arrestin, a protein that sends signals in the body. This structure was determined using an X-ray free electron laser.

Protein Data Bank.

View Media

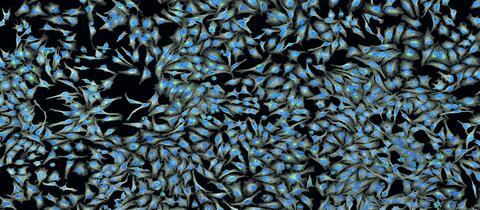

5761: A panorama view of cells

5761: A panorama view of cells

This photograph shows a panoramic view of HeLa cells, a cell line many researchers use to study a large variety of important research questions. The cells' nuclei containing the DNA are stained in blue and the cells' cytoskeletons in gray.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media

3332: Polarized cells- 01

3332: Polarized cells- 01

Cells move forward with lamellipodia and filopodia supported by networks and bundles of actin filaments. Proper, controlled cell movement is a complex process. Recent research has shown that an actin-polymerizing factor called the Arp2/3 complex is the key component of the actin polymerization engine that drives amoeboid cell motility. ARPC3, a component of the Arp2/3 complex, plays a critical role in actin nucleation. In this photo, the ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells were fixed and stained with Alexa 546 phalloidin for F-actin (red) and DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells with lamellipodia leading edge. Related to images 3328, 3329, 3330, 3331, and 3333.

Rong Li and Praveen Suraneni, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

View Media

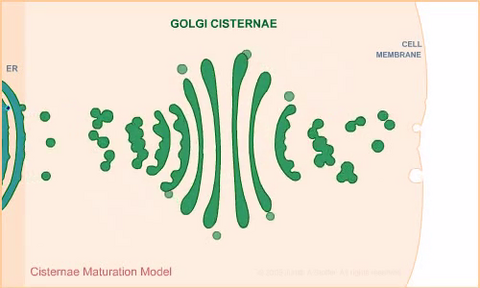

1307: Cisternae maturation model

1307: Cisternae maturation model

Animation for the cisternae maturation model of Golgi transport.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

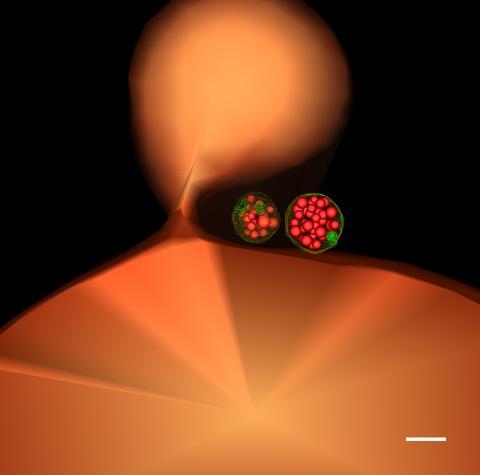

5769: Multivesicular bodies containing intralumenal vesicles assemble at the vacuole 1

5769: Multivesicular bodies containing intralumenal vesicles assemble at the vacuole 1

Collecting and transporting cellular waste and sorting it into recylable and nonrecylable pieces is a complex business in the cell. One key player in that process is the endosome, which helps collect, sort and transport worn-out or leftover proteins with the help of a protein assembly called the endosomal sorting complexes for transport (or ESCRT for short). These complexes help package proteins marked for breakdown into intralumenal vesicles, which, in turn, are enclosed in multivesicular bodies for transport to the places where the proteins are recycled or dumped. In this image, two multivesicular bodies (with yellow membranes) contain tiny intralumenal vesicles (with a diameter of only 25 nanometers; shown in red) adjacent to the cell's vacuole (in orange).

Scientists working with baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) study the budding inward of the limiting membrane (green lines on top of the yellow lines) into the intralumenal vesicles. This tomogram was shot with a Tecnai F-20 high-energy electron microscope, at 29,000x magnification, with a 0.7-nm pixel, ~4-nm resolution.

To learn more about endosomes, see the Biomedical Beat blog post The Cell’s Mailroom. Related to a microscopy photograph 5768 that was used to generate this illustration and a zoomed-in version 5767 of this illustration.

Scientists working with baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) study the budding inward of the limiting membrane (green lines on top of the yellow lines) into the intralumenal vesicles. This tomogram was shot with a Tecnai F-20 high-energy electron microscope, at 29,000x magnification, with a 0.7-nm pixel, ~4-nm resolution.

To learn more about endosomes, see the Biomedical Beat blog post The Cell’s Mailroom. Related to a microscopy photograph 5768 that was used to generate this illustration and a zoomed-in version 5767 of this illustration.

Matthew West and Greg Odorizzi, University of Colorado

View Media

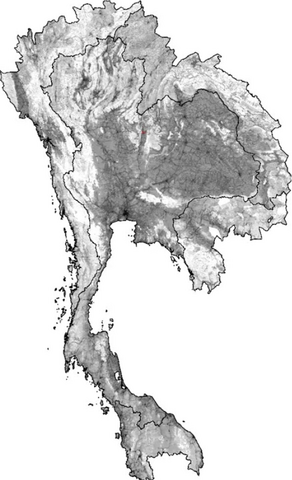

2574: Simulation of uncontrolled avian flu outbreak

2574: Simulation of uncontrolled avian flu outbreak

This video simulation shows what an uncontrolled outbreak of transmissible avian flu among people living in Thailand might look like. Red indicates new cases while green indicates areas where the epidemic has finished. The video shows the spread of infection and recovery over 300 days in Thailand and neighboring countries.

Neil M. Ferguson, Imperial College London

View Media

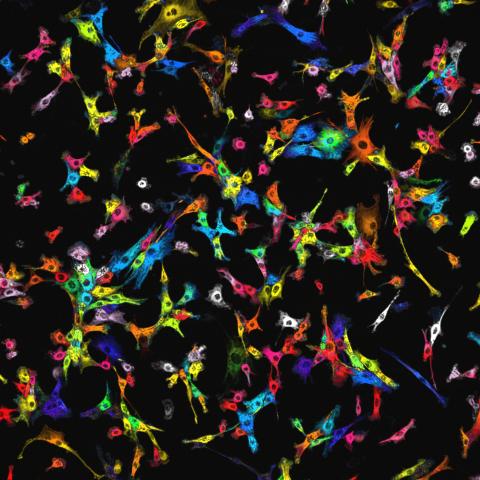

7021: Single-cell “radios” image

7021: Single-cell “radios” image

Individual cells are color-coded based on their identity and signaling activity using a protein circuit technology developed by the Coyle Lab. Just as a radio allows you to listen to an individual frequency, this technology allows researchers to tune into the specific “radio station” of each cell through genetically encoded proteins from a bacterial system called MinDE. The proteins generate an oscillating fluorescent signal that transmits information about cell shape, state, and identity that can be decoded using digital signal processing tools originally designed for telecommunications. The approach allows researchers to look at the dynamics of a single cell in the presence of many other cells.

Related to video 7022.

Related to video 7022.

Scott Coyle, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

View Media

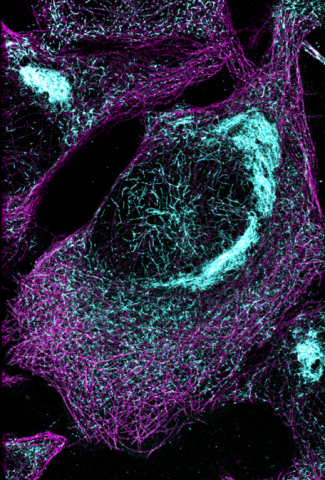

6892: Microtubules and tau aggregates

6892: Microtubules and tau aggregates

Microtubules (magenta) and tau protein (light blue) in a cell model of tauopathy. Researchers believe that tauopathy—the aggregation of tau protein—plays a role in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. This image was captured using Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy (STORM).

Related to images 6889, 6890, and 6891.

Related to images 6889, 6890, and 6891.

Melike Lakadamyali, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

View Media

6557: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 24 hours

6557: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 24 hours

Floral pattern emerging as two bacterial species, motile Acinetobacter baylyi and non-motile Escherichia coli (green), are grown together for 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface from a small inoculum in the center of a Petri dish.

See 6553 for a photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6555 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

See 6553 for a photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6555 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

L. Xiong et al, eLife 2020;9: e48885

View Media

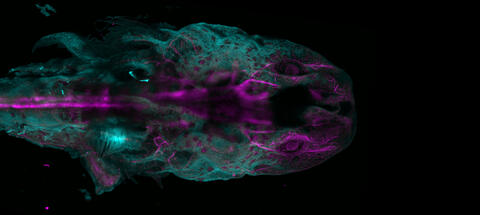

6927: Axolotl showing nervous system

6927: Axolotl showing nervous system

The head of an axolotl—a type of salamander—that has been genetically modified so that its developing nervous system glows purple and its Schwann cell nuclei appear light blue. Schwann cells insulate and provide nutrients to peripheral nerve cells. Researchers often study axolotls for their extensive regenerative abilities. They can regrow tails, limbs, spinal cords, brains, and more. The researcher who took this image focuses on the role of the peripheral nervous system during limb regeneration.

This image was captured using a light sheet microscope.

Related to images 6928 and 6932.

This image was captured using a light sheet microscope.

Related to images 6928 and 6932.

Prayag Murawala, MDI Biological Laboratory and Hannover Medical School.

View Media

1330: Mitosis - prophase

1330: Mitosis - prophase

A cell in prophase, near the start of mitosis: In the nucleus, chromosomes condense and become visible. In the cytoplasm, the spindle forms. Mitosis is responsible for growth and development, as well as for replacing injured or worn out cells throughout the body. For simplicity, mitosis is illustrated here with only six chromosomes.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

2352: Human aspartoacylase

2352: Human aspartoacylase

Model of aspartoacylase, a human enzyme involved in brain metabolism.

Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics, PSI

View Media

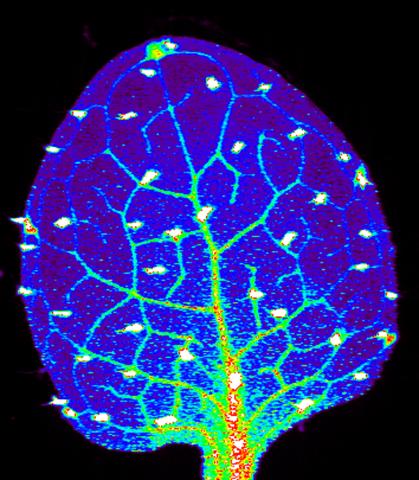

3727: Zinc levels in a plant leaf

3727: Zinc levels in a plant leaf

Zinc is required for the function of more than 300 enzymes, including those that help regulate gene expression, in various organisms including humans. Researchers study how plants acquire, sequester and distribute zinc to find ways to increase the zinc content of crops to improve human health. Using synchrotron X-ray fluorescence technology, they created this heat map of zinc levels in an Arabidopsis thaliana plant leaf. This image is a winner of the 2015 FASEB Bioart contest and was featured in the NIH Director's blog.

Suzana Car, Dartmouth College

View Media

5752: Genetically identical mycobacteria respond differently to antibiotic 2

5752: Genetically identical mycobacteria respond differently to antibiotic 2

Antibiotic resistance in microbes is a serious health concern. So researchers have turned their attention to how bacteria undo the action of some antibiotics. Here, scientists set out to find the conditions that help individual bacterial cells survive in the presence of the antibiotic rifampicin. The research team used Mycobacterium smegmatis, a more harmless relative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which infects the lung and other organs to cause serious disease.

In this video, genetically identical mycobacteria are growing in a miniature growth chamber called a microfluidic chamber. Using live imaging, the researchers found that individual mycobacteria will respond differently to the antibiotic, depending on the growth stage and other timing factors. The researchers used genetic tagging with green fluorescent protein to distinguish cells that can resist rifampicin and those that cannot. With this gene tag, cells tolerant of the antibiotic light up in green and those that are susceptible in violet, enabling the team to monitor the cells' responses in real time.

To learn more about how the researchers studied antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, see this news release from Tufts University. Related to image 5751.

In this video, genetically identical mycobacteria are growing in a miniature growth chamber called a microfluidic chamber. Using live imaging, the researchers found that individual mycobacteria will respond differently to the antibiotic, depending on the growth stage and other timing factors. The researchers used genetic tagging with green fluorescent protein to distinguish cells that can resist rifampicin and those that cannot. With this gene tag, cells tolerant of the antibiotic light up in green and those that are susceptible in violet, enabling the team to monitor the cells' responses in real time.

To learn more about how the researchers studied antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, see this news release from Tufts University. Related to image 5751.

Bree Aldridge, Tufts University

View Media

5896: Stetten Lecture 2017poster image

5896: Stetten Lecture 2017poster image

This image is featured on the poster for Dr. Rommie Amaro's 2017 Stetten Lecture. It depicts a detailed physical model of an influenza virus, incorporating information from several structural data sources. The small molecules around the virus are sialic acid molecules. The virus binds to and cleaves sialic acid as it enters and exits host cells. Researchers are building these highly detailed molecular scale models of different biomedical systems and then “bringing them to life” with physics-based methods, either molecular or Brownian dynamics simulations, to understand the structural dynamics of the systems and their complex interactions with drug or substrate molecules.

Dr. Rommie Amaro, University of California, San Diego

View Media

2377: Protein involved in cell division from Mycoplasma pneumoniae

2377: Protein involved in cell division from Mycoplasma pneumoniae

Model of a protein involved in cell division from Mycoplasma pneumoniae. This model, based on X-ray crystallography, revealed a structural domain not seen before. The protein is thought to be involved in cell division and cell wall biosynthesis.

Berkeley Structural Genomics Center, PSI

View Media

3550: Protein clumping in zinc-deficient yeast cells

3550: Protein clumping in zinc-deficient yeast cells

The green spots in this image are clumps of protein inside yeast cells that are deficient in both zinc and a protein called Tsa1 that prevents clumping. Protein clumping plays a role in many diseases, including Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, where proteins clump together in the brain. Zinc deficiency within a cell can cause proteins to mis-fold and eventually clump together. Normally, in yeast, Tsa1 codes for so-called "chaperone proteins" which help proteins in stressed cells, such as those with a zinc deficiency, fold correctly. The research behind this image was published in 2013 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Colin MacDiarmid and David Eide, University of Wisconsin--Madison

View Media

2380: PanB from M. tuberculosis (1)

2380: PanB from M. tuberculosis (1)

Model of an enzyme, PanB, from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes most cases of tuberculosis. This enzyme is an attractive drug target.

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Center, PSI

View Media

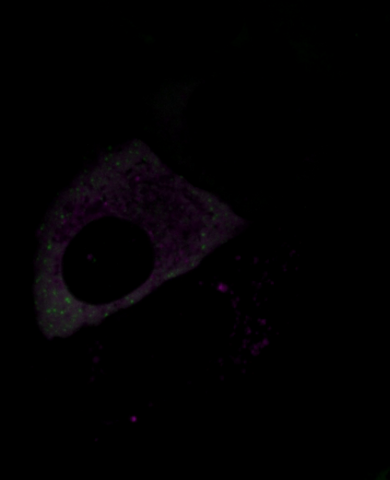

2429: Highlighted cells

2429: Highlighted cells

The cytoskeleton (green) and DNA (purple) are highlighed in these cells by immunofluorescence.

Torsten Wittmann, Scripps Research Institute

View Media

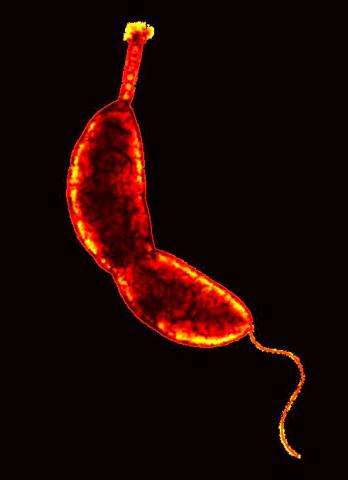

3262: Caulobacter

3262: Caulobacter

A study using Caulobacter crescentus showed that some bacteria use just-in-time processing, much like that used in industrial delivery, to make the glue that allows them to attach to surfaces, an important step in the infection process for many disease-causing bacteria. In the image shown, this freshwater bacterium has a holdfast at the top and a propelling flagellum at the end. From an Indiana University news release.

Yves Brun, Indiana University

View Media

6570: Stress Response in Cells

6570: Stress Response in Cells

Two highly stressed osteosarcoma cells are shown with a set of green droplet-like structures followed by a second set of magenta droplets. These droplets are composed of fluorescently labeled stress-response proteins, either G3BP or UBQLN2 (Ubiquilin-2). Each protein is undergoing a fascinating process, called phase separation, in which a non-membrane bound compartment of the cytoplasm emerges with a distinct environment from the surrounding cytoplasm. Subsequently, the proteins fuse with like proteins to form larger droplets, in much the same way that raindrops merge on a car’s windshield.

Julia F. Riley and Carlos A. Castañeda, Syracuse University

View Media

3525: Bacillus anthracis being killed

3525: Bacillus anthracis being killed

Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) cells being killed by a fluorescent trans-translation inhibitor, which disrupts bacterial protein synthesis. The inhibitor is naturally fluorescent and looks blue when it is excited by ultraviolet light in the microscope. This is a color version of Image 3481.

Kenneth Keiler, Penn State University

View Media

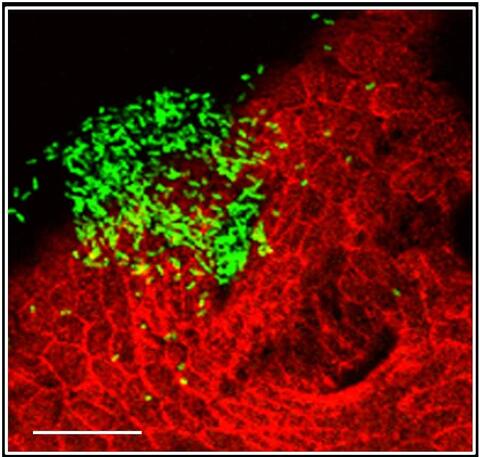

7019: Bacterial cells aggregated above a light-organ pore of the Hawaiian bobtail squid

7019: Bacterial cells aggregated above a light-organ pore of the Hawaiian bobtail squid

The beating of cilia on the outside of the Hawaiian bobtail squid’s light organ concentrates Vibrio fischeri cells (green) present in the seawater into aggregates near the pore-containing tissue (red). From there, the bacterial cells (~2 mm) swim to the pores and migrate through a bottleneck into the interior crypts where a population of symbionts grow and remain for the life of the host. This image was taken using confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Related to images 7016, 7017, 7018, and 7020.

Related to images 7016, 7017, 7018, and 7020.

Margaret J. McFall-Ngai, Carnegie Institution for Science/California Institute of Technology, and Edward G. Ruby, California Institute of Technology.

View Media

2771: Self-organizing proteins

2771: Self-organizing proteins

Under the microscope, an E. coli cell lights up like a fireball. Each bright dot marks a surface protein that tells the bacteria to move toward or away from nearby food and toxins. Using a new imaging technique, researchers can map the proteins one at a time and combine them into a single image. This lets them study patterns within and among protein clusters in bacterial cells, which don't have nuclei or organelles like plant and animal cells. Seeing how the proteins arrange themselves should help researchers better understand how cell signaling works.

View Media

5811: NCMIR Tongue 2

5811: NCMIR Tongue 2

Microscopy image of a tongue. One in a series of two, see image 5810

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media