Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

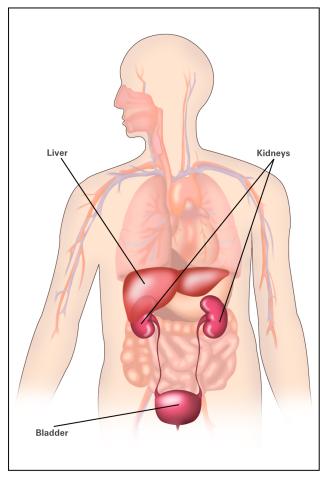

2497: Body toxins (with labels)

2497: Body toxins (with labels)

Body organs such as the liver and kidneys process chemicals and toxins. These "target" organs are susceptible to damage caused by these substances. See image 2496 for an unlabeled version of this illustration.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

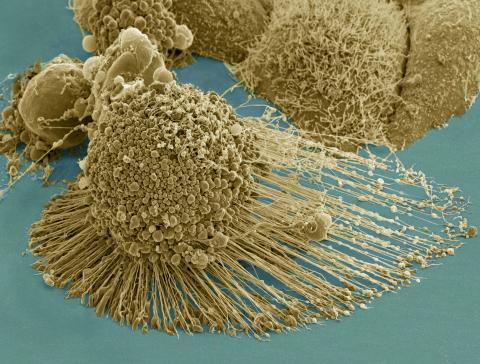

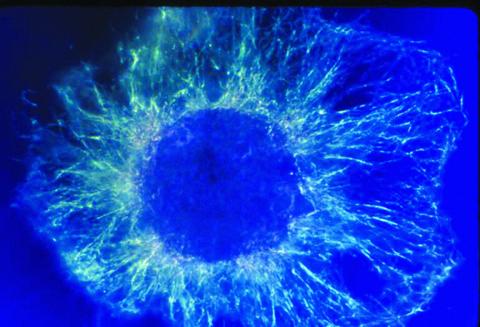

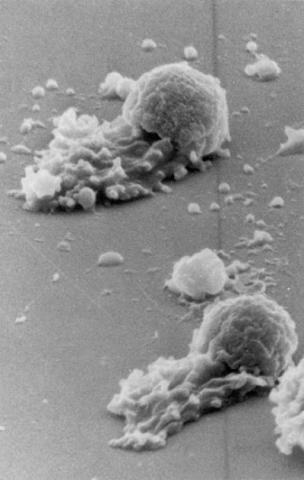

3519: HeLa cells

3519: HeLa cells

Scanning electron micrograph of an apoptotic HeLa cell. Zeiss Merlin HR-SEM. See related images 3518, 3520, 3521, 3522.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media

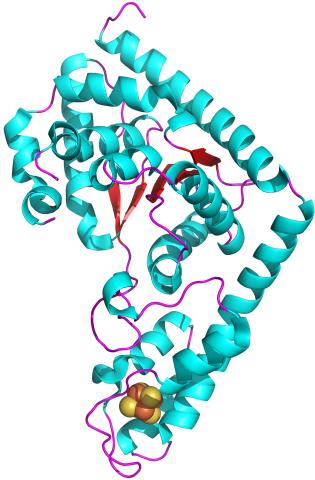

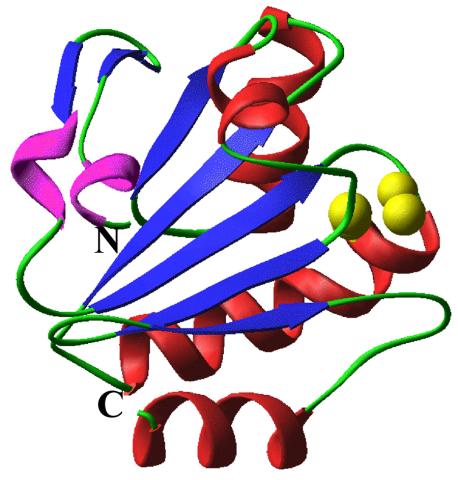

2483: Trp_RS - tryptophanyl tRNA-synthetase family of enzymes

2483: Trp_RS - tryptophanyl tRNA-synthetase family of enzymes

This image represents the structure of TrpRS, a novel member of the tryptophanyl tRNA-synthetase family of enzymes. By helping to link the amino acid tryptophan to a tRNA molecule, TrpRS primes the amino acid for use in protein synthesis. A cluster of iron and sulfur atoms (orange and red spheres) was unexpectedly found in the anti-codon domain, a key part of the molecule, and appears to be critical for the function of the enzyme. TrpRS was discovered in Thermotoga maritima, a rod-shaped bacterium that flourishes in high temperatures.

View Media

2362: Automated crystal screening system

2362: Automated crystal screening system

Automated crystal screening systems such as the one shown here are becoming a common feature at synchrotron and other facilities where high-throughput crystal structure determination is being carried out. These systems rapidly screen samples to identify the best candidates for further study.

Southeast Collaboratory for Structural Genomics

View Media

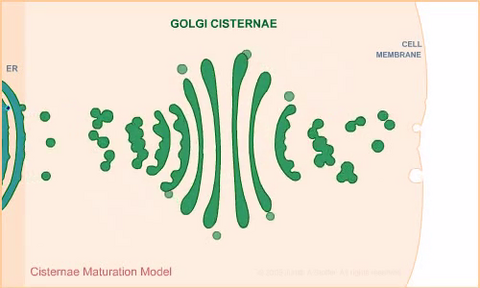

1278: Golgi theories

1278: Golgi theories

Two models for how material passes through the Golgi apparatus: the vesicular shuttle model and the cisternae maturation model.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

6999: HIV enzyme

6999: HIV enzyme

These images model the molecular structures of three enzymes with critical roles in the life cycle of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). At the top, reverse transcriptase (orange) creates a DNA copy (yellow) of the virus's RNA genome (blue). In the middle image, integrase (magenta) inserts this DNA copy in the DNA genome (green) of the infected cell. At the bottom, much later in the viral life cycle, protease (turquoise) chops up a chain of HIV structural protein (purple) to generate the building blocks for making new viruses. See these enzymes in action on PDB 101’s video A Molecular View of HIV Therapy.

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

2576: Cone snail shell

2576: Cone snail shell

A shell from the venomous cone snail Conus omaria, which lives in the Pacific and Indian oceans and eats other snails. University of Utah scientists discovered a new toxin in this snail species' venom, and say it will be a useful tool in designing new medicines for a variety of brain disorders, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, depression, nicotine addiction and perhaps schizophrenia.

Kerry Matz, University of Utah

View Media

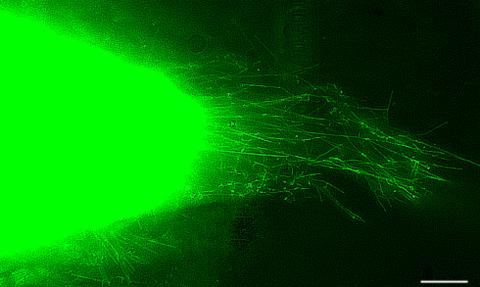

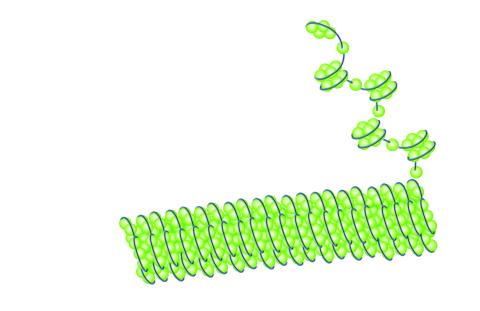

3574: Cytonemes in developing fruit fly cells

3574: Cytonemes in developing fruit fly cells

Scientists have long known that multicellular organisms use biological molecules produced by one cell and sensed by another to transmit messages that, for instance, guide proper development of organs and tissues. But it's been a puzzle as to how molecules dumped out into the fluid-filled spaces between cells can precisely home in on their targets. Using living tissue from fruit flies, a team led by Thomas Kornberg of the University of California, San Francisco, has shown that typical cells in animals can talk to each other via long, thin cell extensions called cytonemes (Latin for "cell threads") that may span the length of 50 or 100 cells. The point of contact between a cytoneme and its target cell acts as a communications bridge between the two cells.

Sougata Roy, University of California, San Francisco

View Media

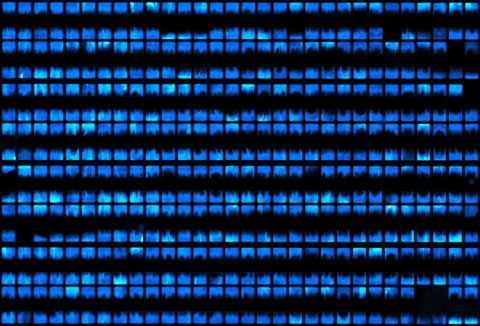

3266: Biopixels

3266: Biopixels

Bioengineers were able to coax bacteria to blink in unison on microfluidic chips. This image shows a small chip with about 500 blinking bacterial colonies or biopixels. Related to images 3265 and 3268. From a UC San Diego news release, "Researchers create living 'neon signs' composed of millions of glowing bacteria."

Jeff Hasty Lab, UC San Diego

View Media

1058: Lily mitosis 01

1058: Lily mitosis 01

A light microscope image shows the chromosomes, stained dark blue, in a dividing cell of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

5758: Migrating pigment cells

5758: Migrating pigment cells

Pigment cells are cells that give skin its color. In fishes and amphibians, like frogs and salamanders, pigment cells are responsible for the characteristic skin patterns that help these organisms to blend into their surroundings or attract mates. The pigment cells are derived from neural crest cells, which are cells originating from the neural tube in the early embryo. This image shows neural crest cell-derived, migrating pigment cells in a salamander. Investigating pigment cell formation and migration in animals helps answer important fundamental questions about the factors that control pigmentation in the skin of animals, including humans. Related to images 5754, 5755, 5756 and 5757.

David Parichy, University of Washington

View Media

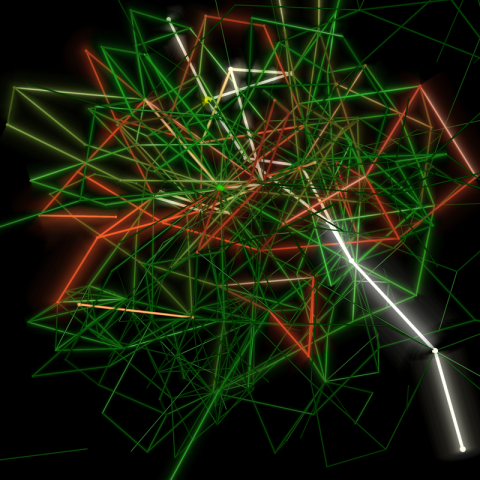

2319: Mapping metabolic activity

2319: Mapping metabolic activity

Like a map showing heavily traveled roads, this mathematical model of metabolic activity inside an E. coli cell shows the busiest pathway in white. Reaction pathways used less frequently by the cell are marked in red (moderate activity) and green (even less activity). Visualizations like this one may help scientists identify drug targets that block key metabolic pathways in bacteria.

Albert-László Barabási, University of Notre Dame

View Media

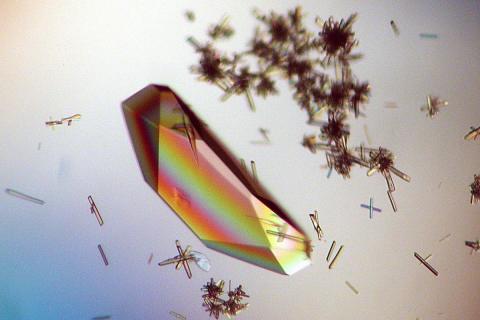

2396: Hen egg lysozyme (1)

2396: Hen egg lysozyme (1)

Crystals of hen egg lysozyme protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

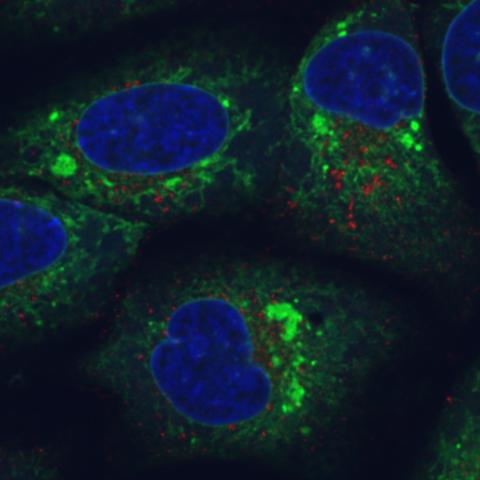

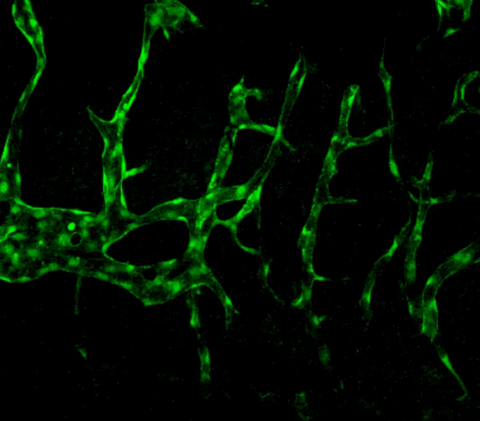

6773: Endoplasmic reticulum abnormalities

6773: Endoplasmic reticulum abnormalities

Human cells with the gene that codes for the protein FIT2 deleted. Green indicates an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resident protein. The lack of FIT2 affected the structure of the ER and caused the resident protein to cluster in ER membrane aggregates, seen as large, bright-green spots. Red shows where the degradation of cell parts—called autophagy—is taking place, and the nucleus is visible in blue. This image was captured using a confocal microscope.

Michel Becuwe, Harvard University.

View Media

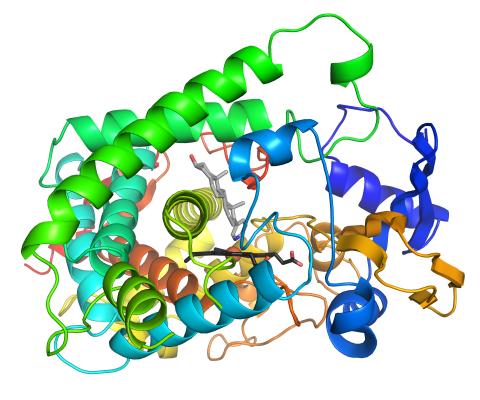

3326: Cytochrome structure with anticancer drug

3326: Cytochrome structure with anticancer drug

This image shows the structure of the CYP17A1 enzyme (ribbons colored from blue N-terminus to red C-terminus), with the associated heme colored black. The prostate cancer drug abiraterone is colored gray. Cytochrome P450 enzymes bind to and metabolize a variety of chemicals, including drugs. Cytochrome P450 17A1 also helps create steroid hormones. Emily Scott's lab is studying how CYP17A1 could be selectively inhibited to treat prostate cancer. She and graduate student Natasha DeVore elucidated the structure shown using X-ray crystallography. Dr. Scott created the image (both white bg and transparent bg) for the NIGMS image gallery. See the "Medium-Resolution Image" for a PNG version of the image that is transparent.

Emily Scott, University of Kansas

View Media

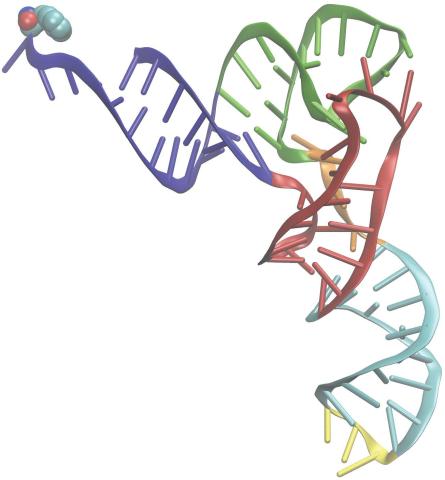

3406: Phenylalanine tRNA molecule

3406: Phenylalanine tRNA molecule

Phenylalanine tRNA showing the anticodon (yellow) and the amino acid, phenylalanine (blue and red spheres).

Patrick O'Donoghue and Dieter Soll, Yale University

View Media

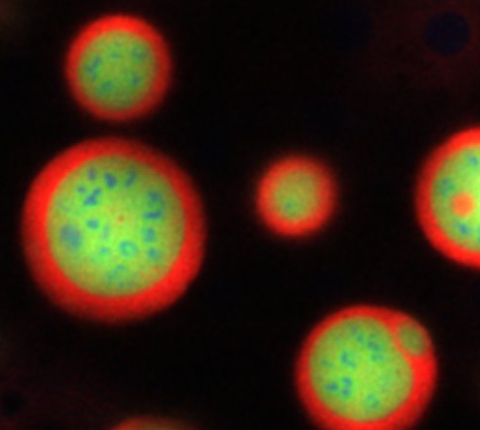

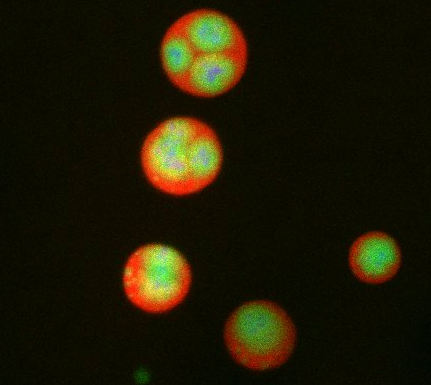

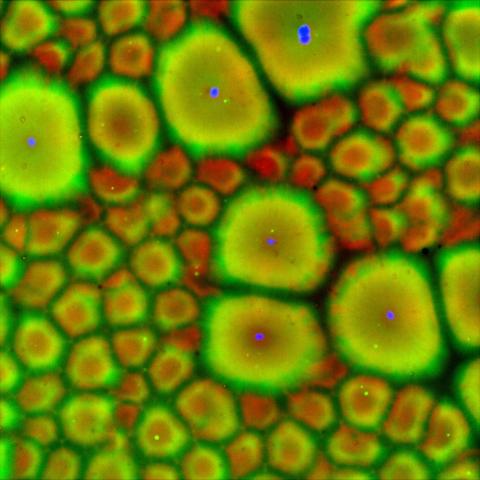

3793: Nucleolus subcompartments spontaneously self-assemble 4

3793: Nucleolus subcompartments spontaneously self-assemble 4

What looks a little like distant planets with some mysterious surface features are actually assemblies of proteins normally found in the cell's nucleolus, a small but very important protein complex located in the cell's nucleus. It forms on the chromosomes at the location where the genes for the RNAs are that make up the structure of the ribosome, the indispensable cellular machine that makes proteins from messenger RNAs.

However, how the nucleolus grows and maintains its structure has puzzled scientists for some time. It turns out that even though it looks like a simple liquid blob, it's rather well-organized, consisting of three distinct layers: the fibrillar center, where the RNA polymerase is active; the dense fibrillar component, which is enriched in the protein fibrillarin; and the granular component, which contains a protein called nucleophosmin. Researchers have now discovered that this multilayer structure of the nucleolus arises from differences in how the proteins in each compartment mix with water and with each other. These differences let the proteins readily separate from each other into the three nucleolus compartments.

This photo of nucleolus proteins in the eggs of a commonly used lab animal, the frog Xenopus laevis, shows each of the nucleolus compartments (the granular component is shown in red, the fibrillarin in yellow-green, and the fibrillar center in blue). The researchers have found that these compartments spontaneously fuse with each other on encounter without mixing with the other compartments.

For more details on this research, see this press release from Princeton. Related to video 3789, video 3791 and image 3792.

However, how the nucleolus grows and maintains its structure has puzzled scientists for some time. It turns out that even though it looks like a simple liquid blob, it's rather well-organized, consisting of three distinct layers: the fibrillar center, where the RNA polymerase is active; the dense fibrillar component, which is enriched in the protein fibrillarin; and the granular component, which contains a protein called nucleophosmin. Researchers have now discovered that this multilayer structure of the nucleolus arises from differences in how the proteins in each compartment mix with water and with each other. These differences let the proteins readily separate from each other into the three nucleolus compartments.

This photo of nucleolus proteins in the eggs of a commonly used lab animal, the frog Xenopus laevis, shows each of the nucleolus compartments (the granular component is shown in red, the fibrillarin in yellow-green, and the fibrillar center in blue). The researchers have found that these compartments spontaneously fuse with each other on encounter without mixing with the other compartments.

For more details on this research, see this press release from Princeton. Related to video 3789, video 3791 and image 3792.

Nilesh Vaidya, Princeton University

View Media

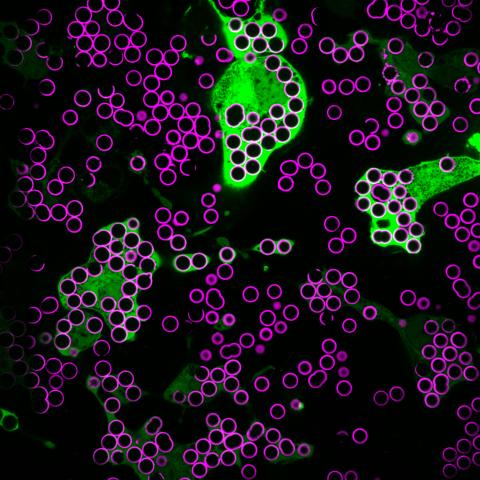

7009: Hungry, hungry macrophages

7009: Hungry, hungry macrophages

Macrophages (green) are the professional eaters of our immune system. They are constantly surveilling our tissues for targets—such as bacteria, dead cells, or even cancer—and clearing them before they can cause harm. In this image, researchers were testing how macrophages responded to different molecules that were attached to silica beads (magenta) coated with a lipid bilayer to mimic a cell membrane.

Find more information on this image in the NIH Director’s Blog post "How to Feed a Macrophage."

Find more information on this image in the NIH Director’s Blog post "How to Feed a Macrophage."

Meghan Morrissey, University of California, Santa Barbara.

View Media

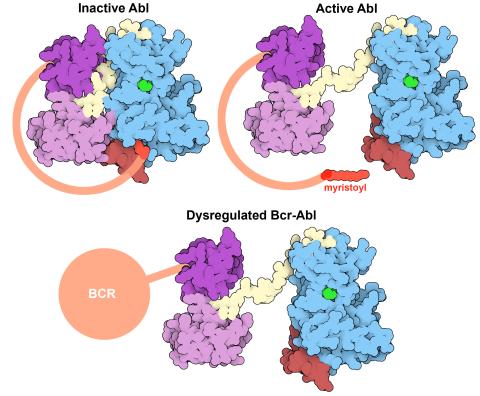

7004: Protein kinases as cancer chemotherapy targets

7004: Protein kinases as cancer chemotherapy targets

Protein kinases—enzymes that add phosphate groups to molecules—are cancer chemotherapy targets because they play significant roles in almost all aspects of cell function, are tightly regulated, and contribute to the development of cancer and other diseases if any alterations to their regulation occur. Genetic abnormalities affecting the c-Abl tyrosine kinase are linked to chronic myelogenous leukemia, a cancer of immature cells in the bone marrow. In the noncancerous form of the protein, binding of a myristoyl group to the kinase domain inhibits the activity of the protein until it is needed (top left shows the inactive form, top right shows the open and active form). The cancerous variant of the protein, called Bcr-Abl, lacks this autoinhibitory myristoyl group and is continually active (bottom). ATP is shown in green bound in the active site of the kinase.

Find these in the RCSB Protein Data Bank: c-Abl tyrosine kinase and regulatory domains (PDB entry 1OPL) and F-actin binding domain (PDB entry 1ZZP).

Find these in the RCSB Protein Data Bank: c-Abl tyrosine kinase and regulatory domains (PDB entry 1OPL) and F-actin binding domain (PDB entry 1ZZP).

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

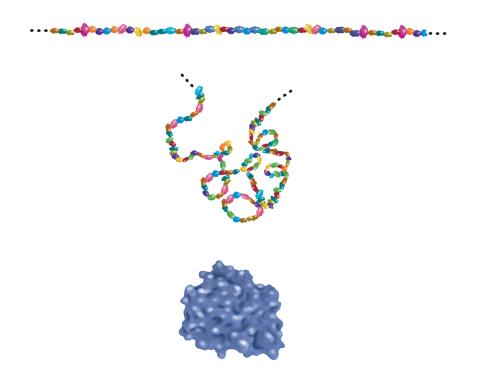

2508: Building blocks and folding of proteins

2508: Building blocks and folding of proteins

Proteins are made of amino acids hooked end-to-end like beads on a necklace. To become active, proteins must twist and fold into their final, or "native," conformation. A protein's final shape enables it to accomplish its function. Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

3737: A bundle of myelinated peripheral nerve cells (axons)

3737: A bundle of myelinated peripheral nerve cells (axons)

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is most prevalent in connective tissues but also is present between the stems (axons) of nerve cells. The axons of nerve cells are surrounded by the ECM encasing myelin-supplying Schwann cells, which insulate the axons to help speed the transmission of electric nerve impulses along the axons.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

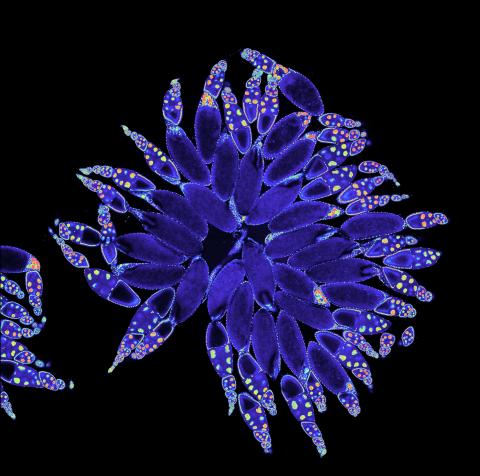

3607: Fruit fly ovary

3607: Fruit fly ovary

A fruit fly ovary, shown here, contains as many as 20 eggs. Fruit flies are not merely tiny insects that buzz around overripe fruit—they are a venerable scientific tool. Research on the flies has shed light on many aspects of human biology, including biological rhythms, learning, memory, and neurodegenerative diseases. Another reason fruit flies are so useful in a lab (and so successful in fruit bowls) is that they reproduce rapidly. About three generations can be studied in a single month.

Related to image 3656. This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Related to image 3656. This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Denise Montell, Johns Hopkins University and University of California, Santa Barbara

View Media

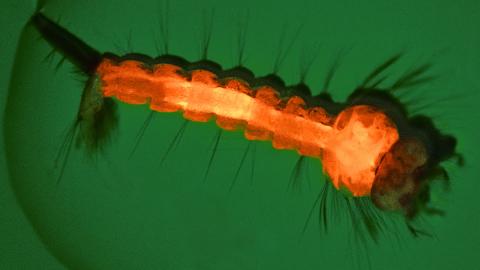

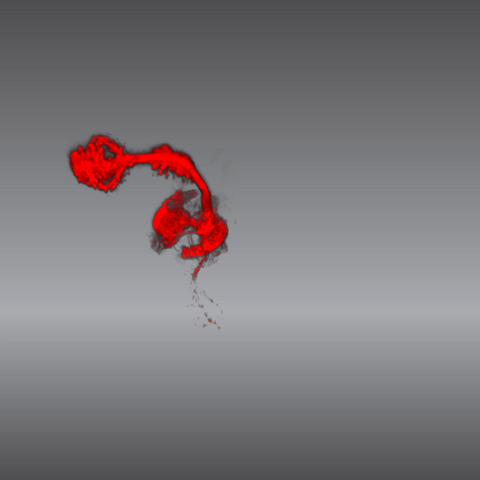

6769: Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito larva

6769: Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito larva

A mosquito larva with genes edited by CRISPR. The red-orange glow is a fluorescent protein used to track the edits. This species of mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus, can transmit West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and avian malaria, among other diseases. The researchers who took this image developed a gene-editing toolkit for Culex quinquefasciatus that could ultimately help stop the mosquitoes from spreading pathogens. The work is described in the Nature Communications paper "Optimized CRISPR tools and site-directed transgenesis towards gene drive development in Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes" by Feng et al. Related to image 6770 and video 6771.

Valentino Gantz, University of California, San Diego.

View Media

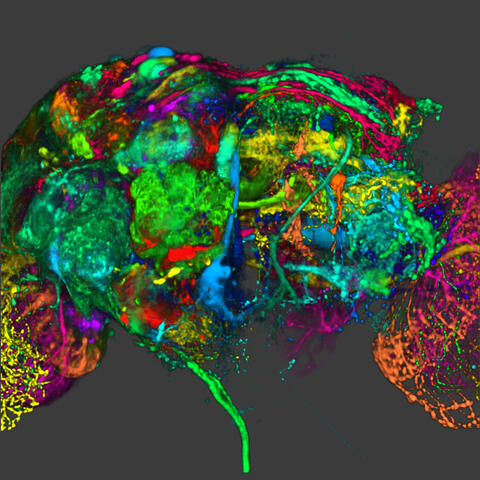

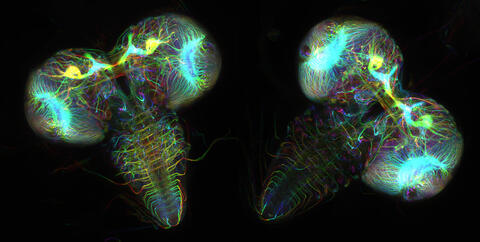

5838: Color coding of the Drosophila brain - image

5838: Color coding of the Drosophila brain - image

This image results from a research project to visualize which regions of the adult fruit fly (Drosophila) brain derive from each neural stem cell. First, researchers collected several thousand fruit fly larvae and fluorescently stained a random stem cell in the brain of each. The idea was to create a population of larvae in which each of the 100 or so neural stem cells was labeled at least once. When the larvae grew to adults, the researchers examined the flies’ brains using confocal microscopy. With this technique, the part of a fly’s brain that derived from a single, labeled stem cell “lights up. The scientists photographed each brain and digitally colorized its lit-up area. By combining thousands of such photos, they created a three-dimensional, color-coded map that shows which part of the Drosophila brain comes from each of its ~100 neural stem cells. In other words, each colored region shows which neurons are the progeny or “clones” of a single stem cell. This work established a hierarchical structure as well as nomenclature for the neurons in the Drosophila brain. Further research will relate functions to structures of the brain.

Related to image 5868 and video 5843

Related to image 5868 and video 5843

Yong Wan from Charles Hansen’s lab, University of Utah. Data preparation and visualization by Masayoshi Ito in the lab of Kei Ito, University of Tokyo.

View Media

1307: Cisternae maturation model

1307: Cisternae maturation model

Animation for the cisternae maturation model of Golgi transport.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

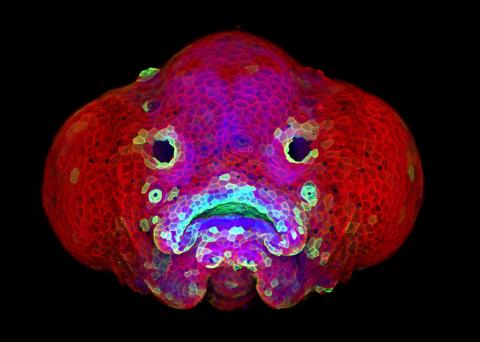

5881: Zebrafish larva

5881: Zebrafish larva

You are face to face with a 6-day-old zebrafish larva. What look like eyes will become nostrils, and the bulges on either side will become eyes. Scientists use fast-growing, transparent zebrafish to see body shapes form and organs develop over the course of just a few days. Images like this one help researchers understand how gene mutations can lead to facial abnormalities such as cleft lip and palate in people.

This image won a 2016 FASEB BioArt award. In addition, NIH Director Francis Collins featured this on his blog on January 26, 2017.

This image won a 2016 FASEB BioArt award. In addition, NIH Director Francis Collins featured this on his blog on January 26, 2017.

Oscar Ruiz and George Eisenhoffer, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

View Media

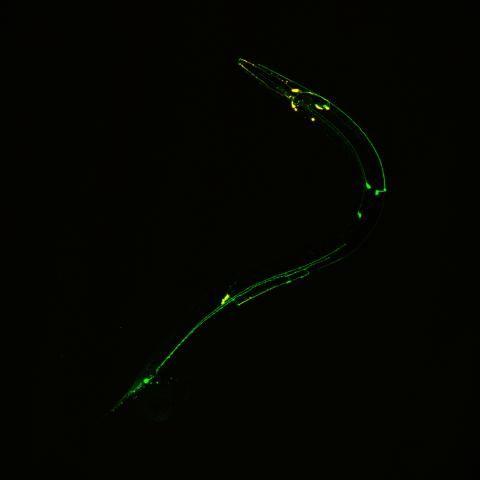

3252: Neural circuits in worms similar to those in humans

3252: Neural circuits in worms similar to those in humans

Green and yellow fluorescence mark the processes and cell bodies of some C. elegans neurons. Researchers have found that the strategies used by this tiny roundworm to control its motions are remarkably similar to those used by the human brain to command movement of our body parts. From a November 2011 University of Michigan news release.

Shawn Xu, University of Michigan

View Media

2802: Biosensors illustration

2802: Biosensors illustration

A rendering of an activity biosensor image overlaid with a cell-centered frame of reference used for image analysis of signal transduction. This is an example of NIH-supported research on single-cell analysis. Related to 2798 , 2799, 2800, 2801 and 2803.

Gaudenz Danuser, Harvard Medical School

View Media

6808: Fruit fly larvae brains showing tubulin

6808: Fruit fly larvae brains showing tubulin

Two fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) larvae brains with neurons expressing fluorescently tagged tubulin protein. Tubulin makes up strong, hollow fibers called microtubules that play important roles in neuron growth and migration during brain development. This image was captured using confocal microscopy, and the color indicates the position of the neurons within the brain.

Vladimir I. Gelfand, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University.

View Media

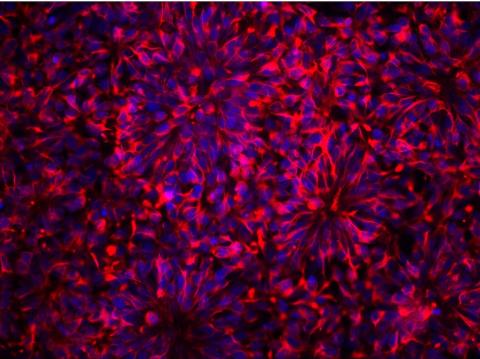

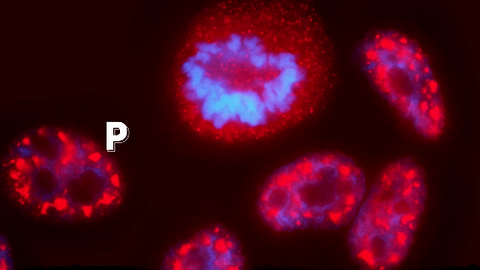

3284: Neurons from human ES cells

3284: Neurons from human ES cells

These neural precursor cells were derived from human embryonic stem cells. The neural cell bodies are stained red, and the nuclei are blue. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Xianmin Zeng lab, Buck Institute for Age Research, via CIRM

View Media

3739: Scanning electron microscopy of the ECM on the surface of a calf muscle

3739: Scanning electron microscopy of the ECM on the surface of a calf muscle

This image shows the extracellular matrix (ECM) on the surface of a soleus (lower calf) muscle in light brown and blood vessels in pink. Near the bottom of the photo, a vessel is opened up to reveal red blood cells. Scientists know less about the ECM in muscle than in other tissues, but it's increasingly clear that the ECM is critical to muscle function, and disruption of the ECM has been associated with many muscle disorders. The ECM in muscles stores and releases growth factors, suggesting that it might play a role in cellular communication.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

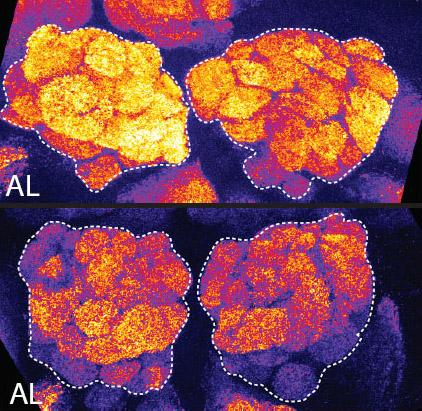

2596: Sleep and the fly brain

2596: Sleep and the fly brain

In the top snapshots, the brain of a sleep-deprived fruit fly glows orange, marking high concentrations of a synaptic protein called Bruchpilot (BRP) involved in communication between neurons. The color particularly lights up brain areas associated with learning. By contrast, the bottom images from a well-rested fly show lower levels of the protein. These pictures illustrate the results of an April 2009 study showing that sleep reduces the protein's levels, suggesting that such "downscaling" resets the brain to normal levels of synaptic activity and makes it ready to learn after a restful night.

Chiara Cirelli, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

1091: Nerve and glial cells in fruit fly embryo

1091: Nerve and glial cells in fruit fly embryo

Glial cells (stained green) in a fruit fly developing embryo have survived thanks to a signaling pathway initiated by neighboring nerve cells (stained red).

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

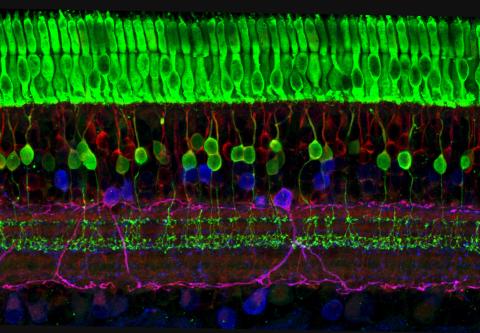

3635: The eye uses many layers of nerve cells to convert light into sight

3635: The eye uses many layers of nerve cells to convert light into sight

This image captures the many layers of nerve cells in the retina. The top layer (green) is made up of cells called photoreceptors that convert light into electrical signals to relay to the brain. The two best-known types of photoreceptor cells are rod- and cone-shaped. Rods help us see under low-light conditions but can't help us distinguish colors. Cones don't function well in the dark but allow us to see vibrant colors in daylight.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Wei Li, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health

View Media

6573: Nuclear Lamina – Three Views

6573: Nuclear Lamina – Three Views

Three views of the entire nuclear lamina of a HeLa cell produced by tilted light sheet 3D single-molecule super-resolution imaging using a platform termed TILT3D.

See 6572 for a 3D view of this structure.

See 6572 for a 3D view of this structure.

Anna-Karin Gustavsson, Ph.D.

View Media

6541: Pathways: What's the Connection? | Different Jobs in a Science Lab

6541: Pathways: What's the Connection? | Different Jobs in a Science Lab

Learn about some of the different jobs in a scientific laboratory and how researchers work as a team to make discoveries. Discover more resources from NIGMS’ Pathways collaboration with Scholastic. View the video on YouTube for closed captioning.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

2441: Hydra 05

2441: Hydra 05

Hydra magnipapillata is an invertebrate animal used as a model organism to study developmental questions, for example the formation of the body axis.

Hiroshi Shimizu, National Institute of Genetics in Mishima, Japan

View Media

2793: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with hydrogens 04

2793: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with hydrogens 04

Ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743, brand name Yondelis), was discovered and isolated from a sea squirt, Ecteinascidia turbinata, by NIGMS grantee Kenneth Rinehart at the University of Illinois. It was synthesized by NIGMS grantees E.J. Corey and later by Samuel Danishefsky. Multiple versions of this structure are available as entries 2790-2797.

Timothy Jamison, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

View Media

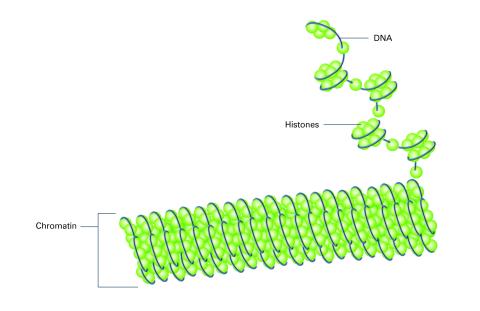

2561: Histones in chromatin (with labels)

2561: Histones in chromatin (with labels)

Histone proteins loop together with double-stranded DNA to form a structure that resembles beads on a string. See image 2560 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

5843: Color coding of the Drosophila brain - video

5843: Color coding of the Drosophila brain - video

This video results from a research project to visualize which regions of the adult fruit fly (Drosophila) brain derive from each neural stem cell. First, researchers collected several thousand fruit fly larvae and fluorescently stained a random stem cell in the brain of each. The idea was to create a population of larvae in which each of the 100 or so neural stem cells was labeled at least once. When the larvae grew to adults, the researchers examined the flies’ brains using confocal microscopy. With this technique, the part of a fly’s brain that derived from a single, labeled stem cell “lights up.” The scientists photographed each brain and digitally colorized its lit-up area. By combining thousands of such photos, they created a three-dimensional, color-coded map that shows which part of the Drosophila brain comes from each of its ~100 neural stem cells. In other words, each colored region shows which neurons are the progeny or “clones” of a single stem cell. This work established a hierarchical structure as well as nomenclature for the neurons in the Drosophila brain. Further research will relate functions to structures of the brain.

Related to images 5838 and 5868.

Related to images 5838 and 5868.

Yong Wan from Charles Hansen’s lab, University of Utah. Data preparation and visualization by Masayoshi Ito in the lab of Kei Ito, University of Tokyo.

View Media

3489: Worm sperm

3489: Worm sperm

To develop a system for studying cell motility in unnatrual conditions -- a microscope slide instead of the body -- Tom Roberts and Katsuya Shimabukuro at Florida State University disassembled and reconstituted the motility parts used by worm sperm cells.

Tom Roberts, Florida State University

View Media

3404: Normal vascular development in frog embryos

3404: Normal vascular development in frog embryos

Hye Ji Cha, University of Texas at Austin

View Media

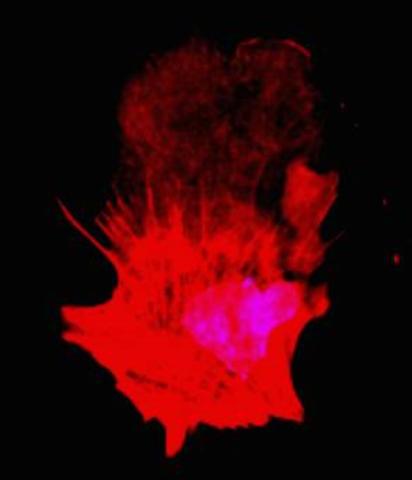

3332: Polarized cells- 01

3332: Polarized cells- 01

Cells move forward with lamellipodia and filopodia supported by networks and bundles of actin filaments. Proper, controlled cell movement is a complex process. Recent research has shown that an actin-polymerizing factor called the Arp2/3 complex is the key component of the actin polymerization engine that drives amoeboid cell motility. ARPC3, a component of the Arp2/3 complex, plays a critical role in actin nucleation. In this photo, the ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells were fixed and stained with Alexa 546 phalloidin for F-actin (red) and DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells with lamellipodia leading edge. Related to images 3328, 3329, 3330, 3331, and 3333.

Rong Li and Praveen Suraneni, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

View Media

3792: Nucleolus subcompartments spontaneously self-assemble 3

3792: Nucleolus subcompartments spontaneously self-assemble 3

What looks a little like distant planets with some mysterious surface features are actually assemblies of proteins normally found in the cell's nucleolus, a small but very important protein complex located in the cell's nucleus. It forms on the chromosomes at the location where the genes for the RNAs are that make up the structure of the ribosome, the indispensable cellular machine that makes proteins from messenger RNAs.

However, how the nucleolus grows and maintains its structure has puzzled scientists for some time. It turns out that even though it looks like a simple liquid blob, it's rather well-organized, consisting of three distinct layers: the fibrillar center, where the RNA polymerase is active; the dense fibrillar component, which is enriched in the protein fibrillarin; and the granular component, which contains a protein called nucleophosmin. Researchers have now discovered that this multilayer structure of the nucleolus arises from differences in how the proteins in each compartment mix with water and with each other. These differences let the proteins readily separate from each other into the three nucleolus compartments.

This photo of nucleolus proteins in the eggs of a commonly used lab animal, the frog Xenopus laevis, shows each of the nucleolus compartments (the granular component is shown in red, the fibrillarin in yellow-green, and the fibrillar center in blue). The researchers have found that these compartments spontaneously fuse with each other on encounter without mixing with the other compartments.

For more details on this research, see this press release from Princeton. Related to video 3789, video 3791 and image 3793.

However, how the nucleolus grows and maintains its structure has puzzled scientists for some time. It turns out that even though it looks like a simple liquid blob, it's rather well-organized, consisting of three distinct layers: the fibrillar center, where the RNA polymerase is active; the dense fibrillar component, which is enriched in the protein fibrillarin; and the granular component, which contains a protein called nucleophosmin. Researchers have now discovered that this multilayer structure of the nucleolus arises from differences in how the proteins in each compartment mix with water and with each other. These differences let the proteins readily separate from each other into the three nucleolus compartments.

This photo of nucleolus proteins in the eggs of a commonly used lab animal, the frog Xenopus laevis, shows each of the nucleolus compartments (the granular component is shown in red, the fibrillarin in yellow-green, and the fibrillar center in blue). The researchers have found that these compartments spontaneously fuse with each other on encounter without mixing with the other compartments.

For more details on this research, see this press release from Princeton. Related to video 3789, video 3791 and image 3793.

Nilesh Vaidya, Princeton University

View Media

2351: tRNA splicing enzyme endonuclease in humans

2351: tRNA splicing enzyme endonuclease in humans

An NMR solution structure model of the transfer RNA splicing enzyme endonuclease in humans (subunit Sen15). This represents the first structure of a eukaryotic tRNA splicing endonuclease subunit.

Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics, PSI

View Media

2382: PanB from M. tuberculosis (2)

2382: PanB from M. tuberculosis (2)

Model of an enzyme, PanB, from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes most cases of tuberculosis. This enzyme is an attractive drug target.

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Center, PSI-1

View Media

1332: Mitosis - telophase

1332: Mitosis - telophase

Telophase during mitosis: Nuclear membranes form around each of the two sets of chromosomes, the chromosomes begin to spread out, and the spindle begins to break down. Mitosis is responsible for growth and development, as well as for replacing injured or worn out cells throughout the body. For simplicity, mitosis is illustrated here with only six chromosomes.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

1047: Sea urchin embryo 01

1047: Sea urchin embryo 01

Stereo triplet of a sea urchin embryo stained to reveal actin filaments (orange) and microtubules (blue). This image is part of a series of images: image 1048, image 1049, image 1050, image 1051 and image 1052.

George von Dassow, University of Washington

View Media

2560: Histones in chromatin

2560: Histones in chromatin

Histone proteins loop together with double-stranded DNA to form a structure that resembles beads on a string. See image 2561 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

6585: Cell-like compartments from frog eggs 2

6585: Cell-like compartments from frog eggs 2

Cell-like compartments that spontaneously emerged from scrambled frog eggs, with nuclei (blue) from frog sperm. Endoplasmic reticulum (red) and microtubules (green) are also visible. Regions without nuclei formed smaller compartments. Image created using epifluorescence microscopy.

For more photos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6584, 6586, 6591, 6592, and 6593.

For videos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6587, 6588, 6589, and 6590.

Xianrui Cheng, Stanford University School of Medicine.

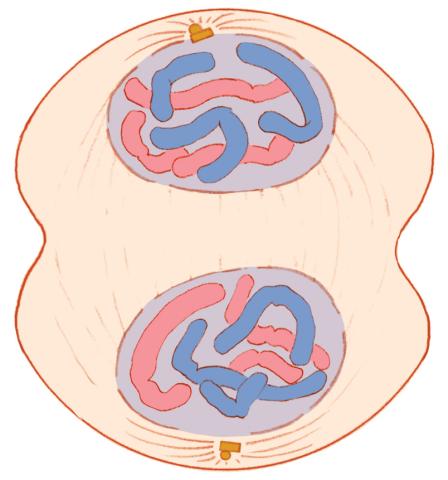

View Media